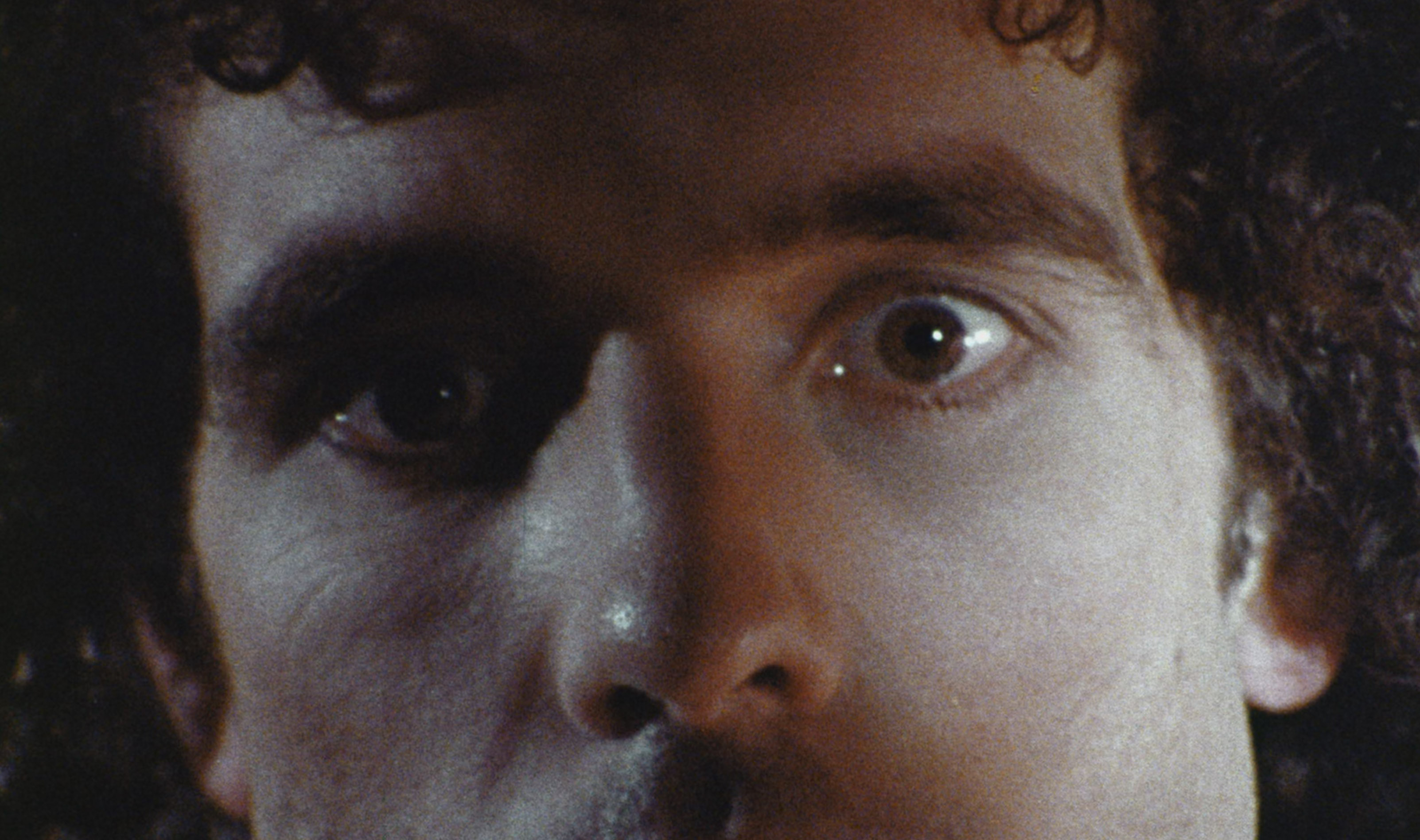

Abel Ferrara’s feature debut (if you don’t count a porno flick he made under a pseudonym in ’76), The Driller Killer, is like most of his other films — gritty, unconventional, and at times, unpleasant to watch. Lacking the hypnotic style that’s more evident in Ferrara’s later efforts, like Ms. 45 and King of New York, this low-budget slasher has still managed to amass a loyal following.

Telling the story of a struggling artist who goes on a power tool killing spree, Driller Killer does manage to break the norms of traditional horror films and has been interpreted by some as a cinematic indictment of New York Bohemianism. While there are flashes of cultural awareness in the movie, it still has the basic nuts and bolts of the grindhouse slasher genre, including several bloody killings, some obligatory nudity, shoddy camerawork and a good helping of bad acting.

Despite not being a huge fan of this movie, I do recognize its cultural significance and can appreciate its depiction of late-seventies NYC (even if a lot of the imagery is dark and murky). Plus, I was informed by a reader that there wasn’t much information out there on its specific filming locations… so far be it from me to pass over an opportunity to power through some location mysteries.

Church

Going into this, there wasn’t a whole lot of specific information out there, other than the rumor that Ferrara filmed inside his real life apartment in the Union Square area of Manhattan. And upon viewing the movie, it became clear fairly quickly that most of the movie was shot in that area, with a few exceptions here and there (this church being one of them).

A lot of these spots were found with help from my research partner, Blakeslee, where he and I would tag-team discoveries and theories to each other until the mystery was solved.

When it came to this church location, it was found by doing a reverse image search using Google Lens. It took several attempts, cropping in on specific elements and using different keywords, until Blakeslee finally got the right combo and hit a match.

This scene was shot at the Chapel of San Lorenzo Ruiz (formerly the Church of the Most Holy Crucifix) on Broome Street, whose exterior was briefly seen in the 1950 noir, Side Street. Sadly, the mid-block chapel was torn down in 2019 and a new unsightly building went up in its place.

In 2024, the ground floor, where this apostolic scene was filmed, was taken over by record label Victor Victor Worldwide as a pop-up store.

What was once a humble Roman Catholic chapel is now a trendy retail space with outrageously overpriced merch and Tweetable paraphernalia.

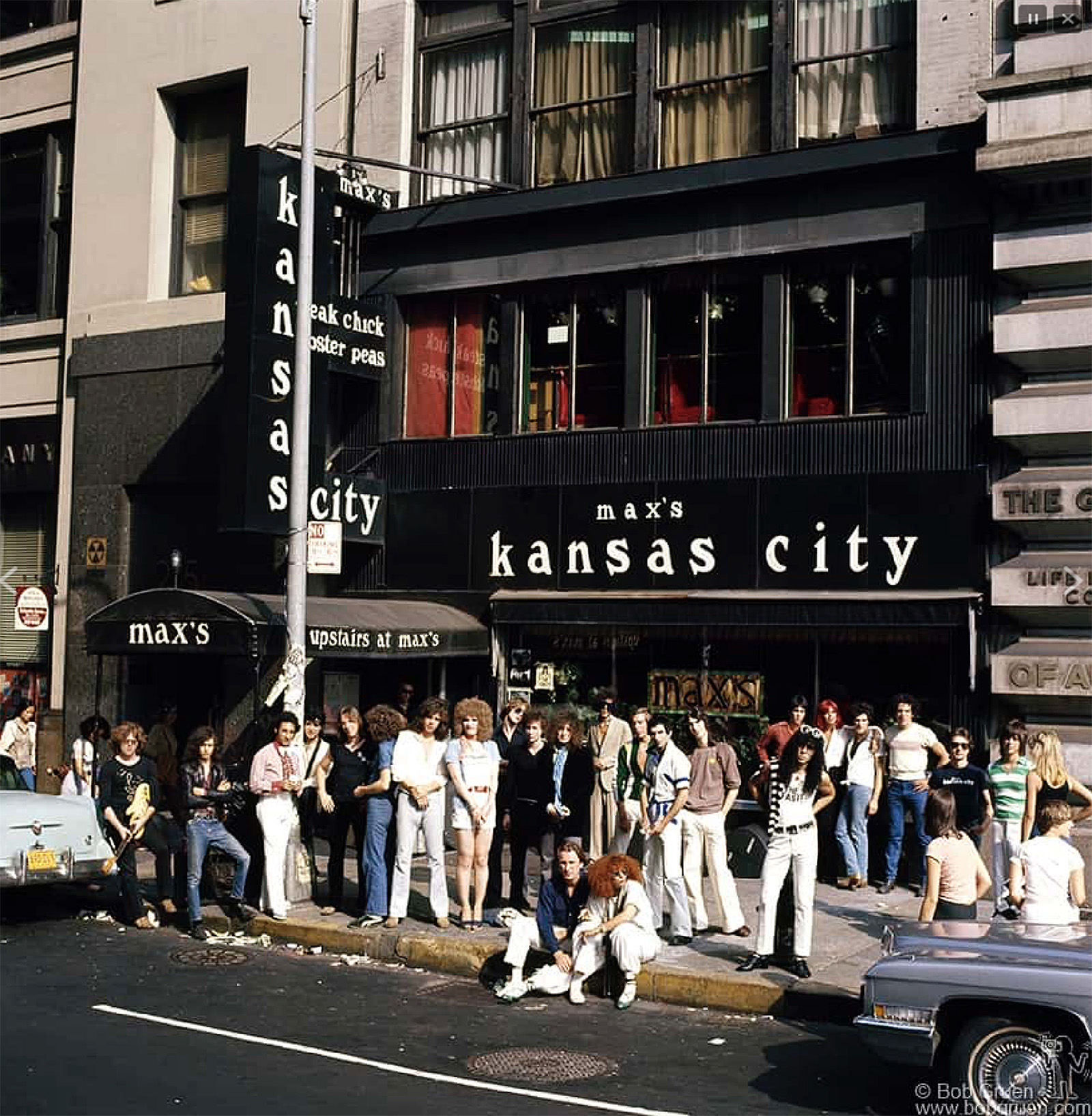

Nightclub

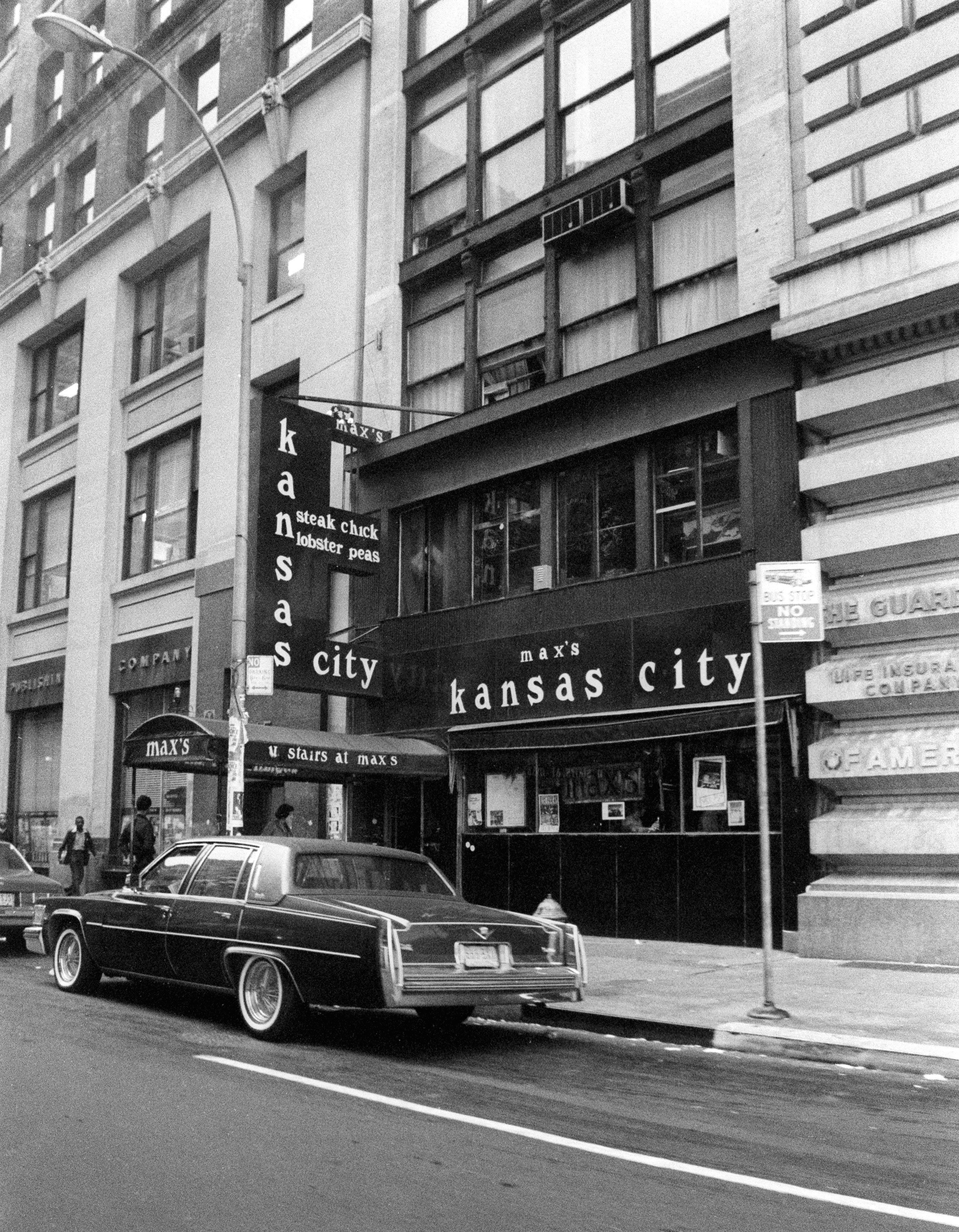

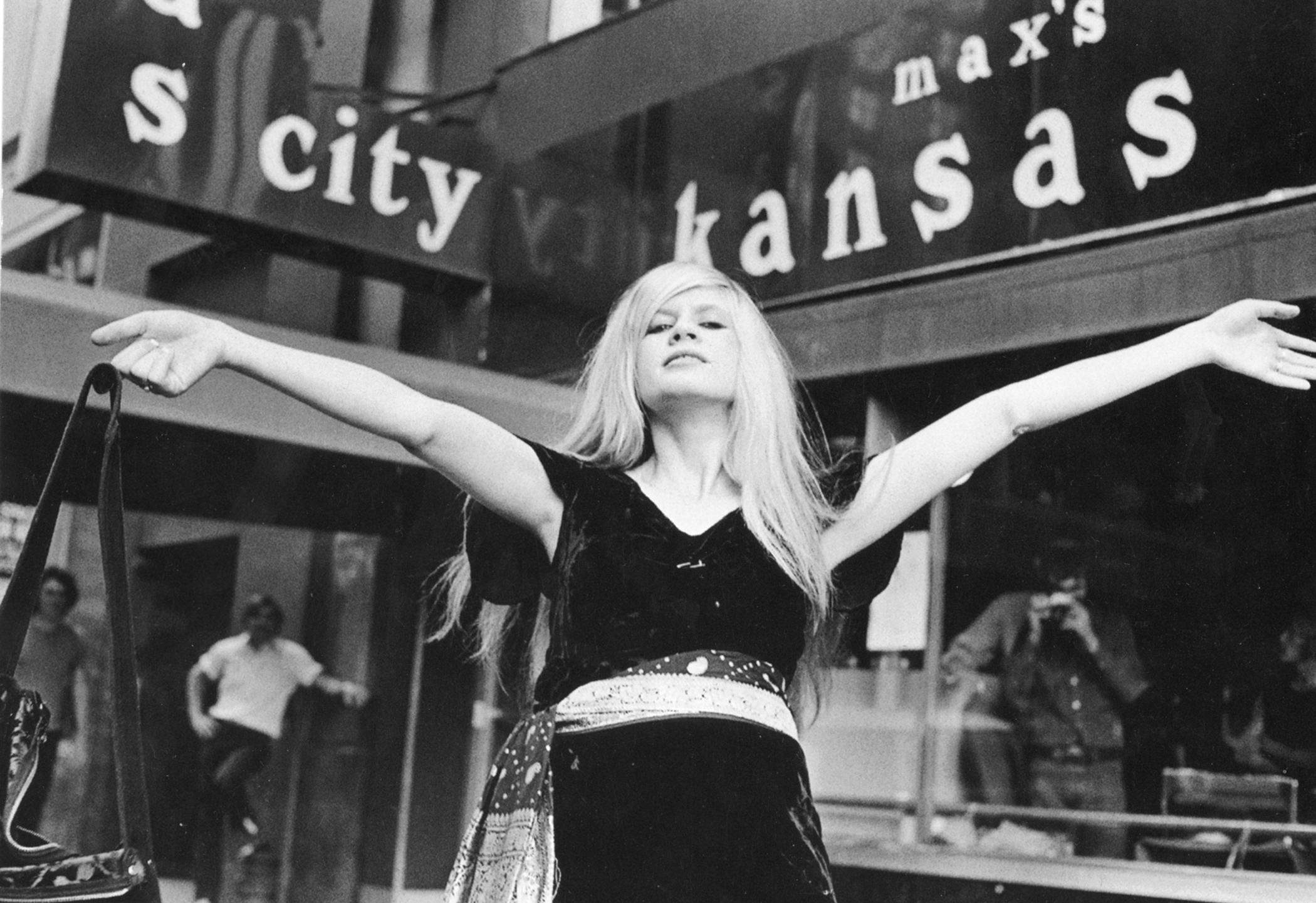

This was easy to find since you can see the club name outside its entrance (although I did have to brighten the image a bit to read it clearly).

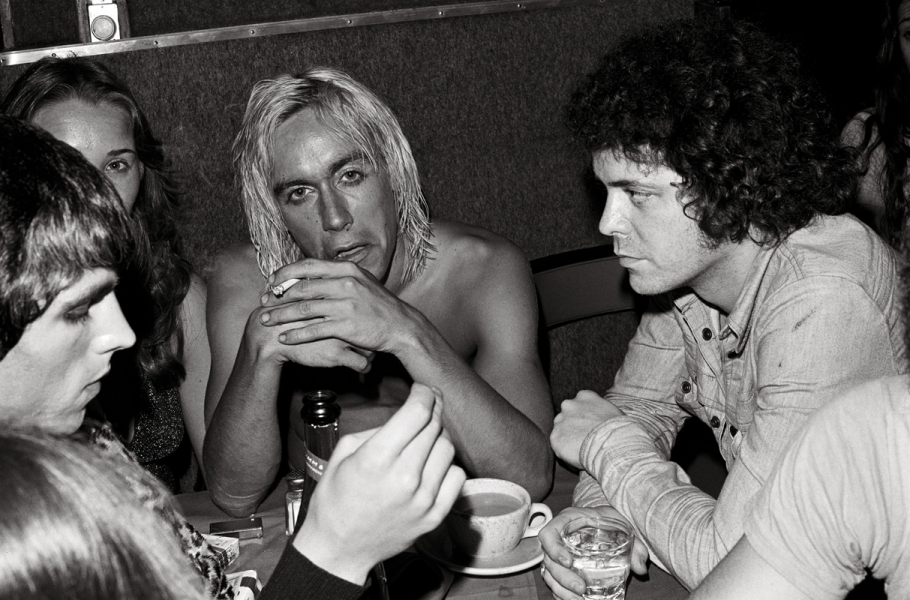

Max’s Kansas City was a pretty unique nightclub and restaurant that was known as a gathering spot for musicians, poets and artists during the sixties and seventies.

Starting off as an art gallery in 1965, Max’s quickly became a hangout for artists of all kinds, especially those from the nearby New York School. It was also a favorite hangout of Andy Warhol and his entourage, including the avant-garde band, The Velvet Underground.

During its lifespan, the club went through several different phases, hosting a variety of musical fads that came and went through the city, and even served as a campaign headquarters for NYC Mayor Ed Koch in 1974.

After briefly closing down, Max’s reopened in 1975 as a music venue for punk bands — one of the first in the country. However, by the time Driller was filmed there, the line-ups were more eclectic, booking all types of underground musicians, including the experimental new wave band, Devo.

Since Max’s Kansas City’s closing in 1981, the Park Avenue space has seen a variety of retailers, most recently a gourmet deli called Fraiche Maxx. However, when I visited the site in the spring of 2025, the store was gone and the space was completely gutted.

A Threesome’s Apartment

In the DVD audio commentary, director Abel Ferrara mentions they filmed the apartment scenes in his real-life apartment at the time on 18th Street. He didn’t give an exact address on the DVD and some contradictory info was floating around the web, but it was eventually figured out by matching up some windows that appear when Reno chucks a telephone out one of them.

After looking around 18th Street, Blakeslee thought those windows looked like the ones along the side of no. 16, which meant the phone landed on the neighboring firehouse’s roof.

Still not 100% certain the exterior was the same place as the interior, I was able to eventually confirm things by matching up the balustrade railing that appears outside the bedroom windows in a later scene (see “Carol Walks Out” below).

What was a crappy low-rent loft in 1979 is now a $15,000/month penthouse apartment that has been sectioned off into several smaller bedrooms and bathrooms.

The apartment still has a second floor bedroom and access to the rooftop (as implied in the movie), and as an added bonus, it now boasts a keyed elevator that opens directly into the living area.

Paying the Electric Bill

This was one of many locations that were easily identifiable, partly due to their close proximity to Union Square Park.

Abel Ferrara, who plays the titular character in the movie, stands in the limestone pavilion at Union Square Park’s north end which used to be a common backdrop for hundreds of labor union demonstrations.

Up until the 1980s, the pavilion also served as a bandstand and an unofficial play space. But today, the nearly century-old structure is used as a Farm-to-Table restaurant, taking advantage of the Farmer’s Market that operates in the park four days a week (although the restaurant’s YELP reviews are far from stunning).

Random Man Gets Stabbed

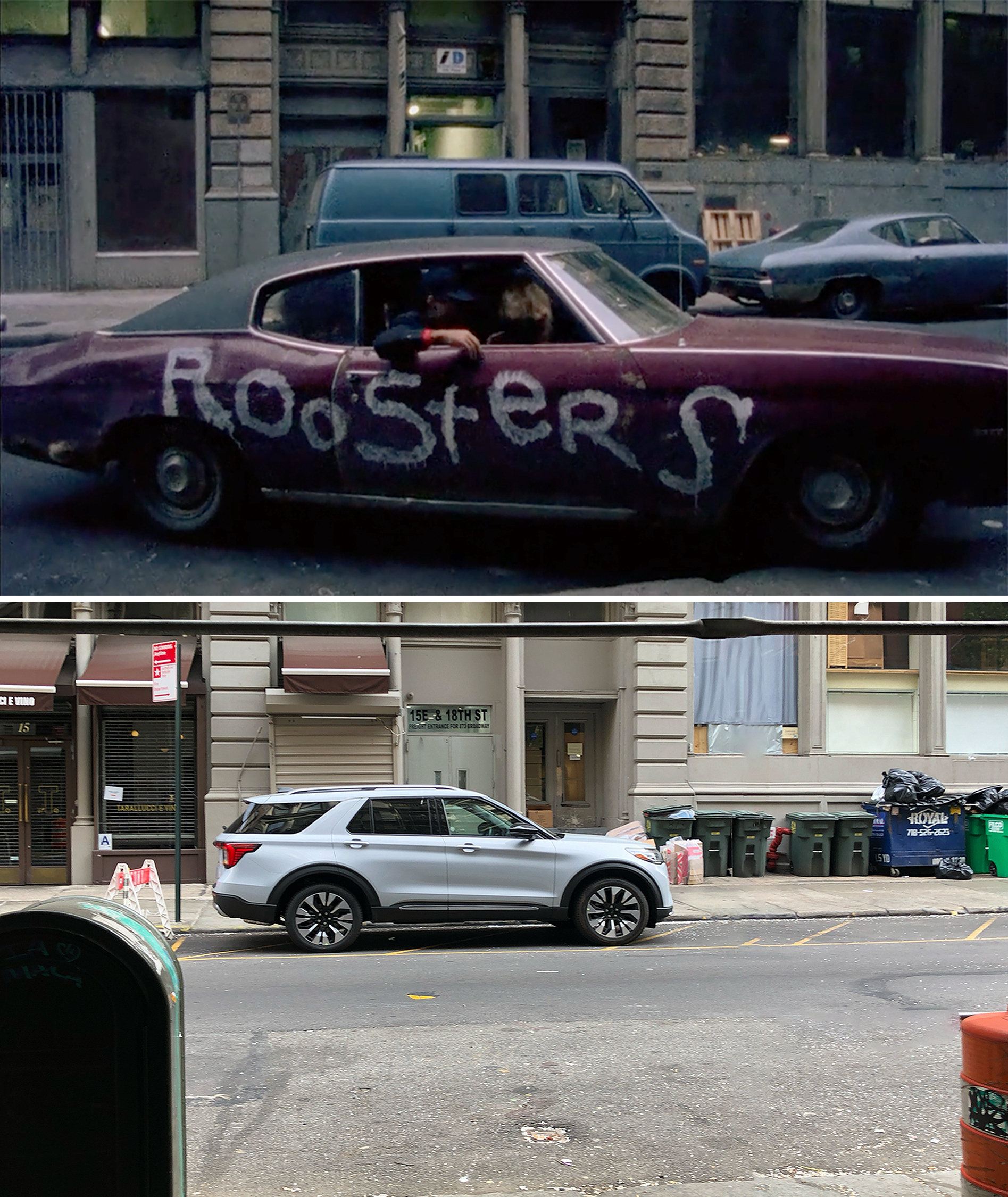

The Roosters Arrive

The Bowery

This location was the last to be found for this movie.

Both in the story and according to the DVD audio commentary, this scene was taking place on Bowery on the Lower East Side. So, I just virtually cruised up and down the street in Google Street View, hoping to find a match. And just in case the building has since-been remodeled or demolished, I also used the interactive 1940s NYC map so I could look through tax photos from circa 1940.

Based on the support post outside the entrance, I assumed the building was on a corner, which I thought would help streamline the process. Unfortunately, after a couple passes, I still couldn’t find a match. Blakeslee gave it a whirl as well, but also came up empty.

We both found several corner buildings with similar support posts, but there were enough inconsistencies that we determined they were not from the movie.

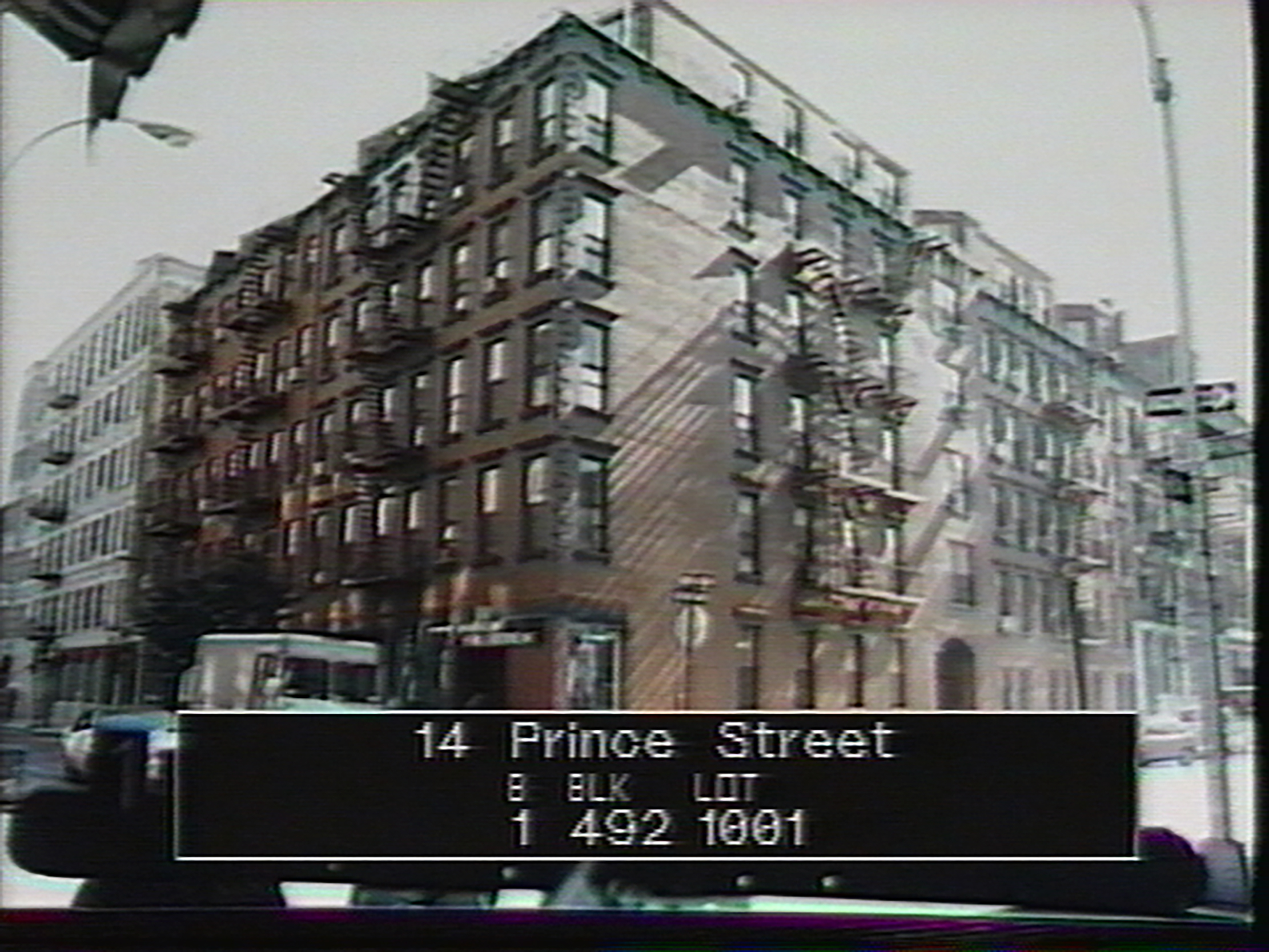

Eventually, I came up with the theory that perhaps Ferrara wasn’t directly on Bowery and that maybe he was one or two blocks away. So, I went back to the 1940s NYC Map and started clicking on corner buildings just off of Bowery, and amazingly, within minutes, I found a promising photo on Prince Street.

The details weren’t great because it was a fairly wide shot, but I could spot several things that matched up. Not only did the support pole look the same, but so did the brick layout below the window as well as a wooden moulding to the left of the window.

The support pole got removed shortly after this film was made, but if you look at a ca 1984 tax photo of the building, the color looked similar to what appeared in this scene.

Also, up until around 2020, the vertical moulding was still in place, solidifying my confidence that I found the right spot.

But sadly, when Barneys New York moved into the retail space, they remodeled the exterior and decided to take down that moulding, thus removing the one last relic from this scene.

You can briefly see the building at 14 Prince in the 1971 low-budget movie, Who Killed Mary What’s ‘Er Name? (AKA, Death of a Hooker), filmed on location in NYC. The benign but entertaining movie stars Red Buttons, Sylvia Miles, Conrad Bain, and a young Sam Waterston.

Teenage Gang

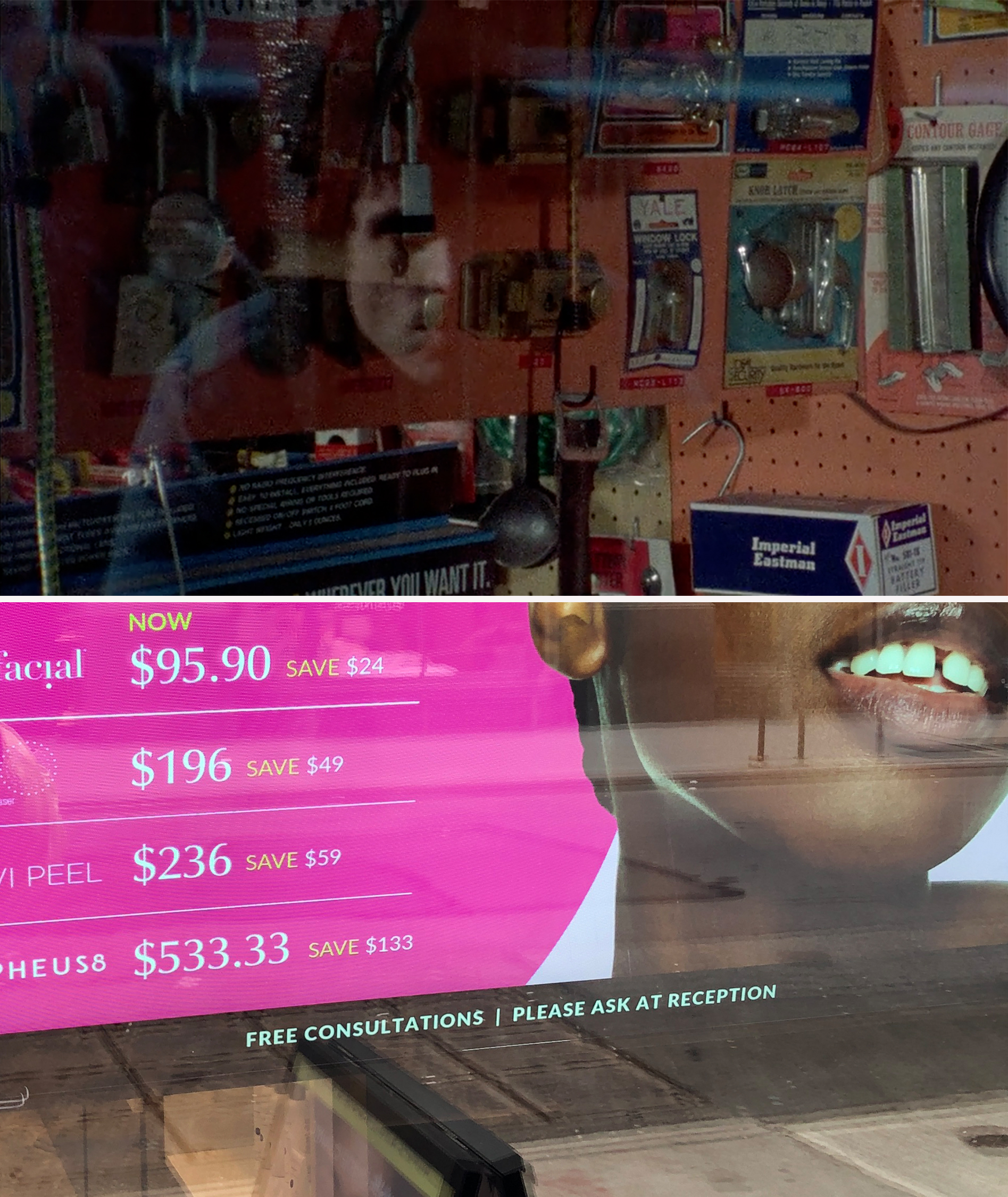

Hardware Store

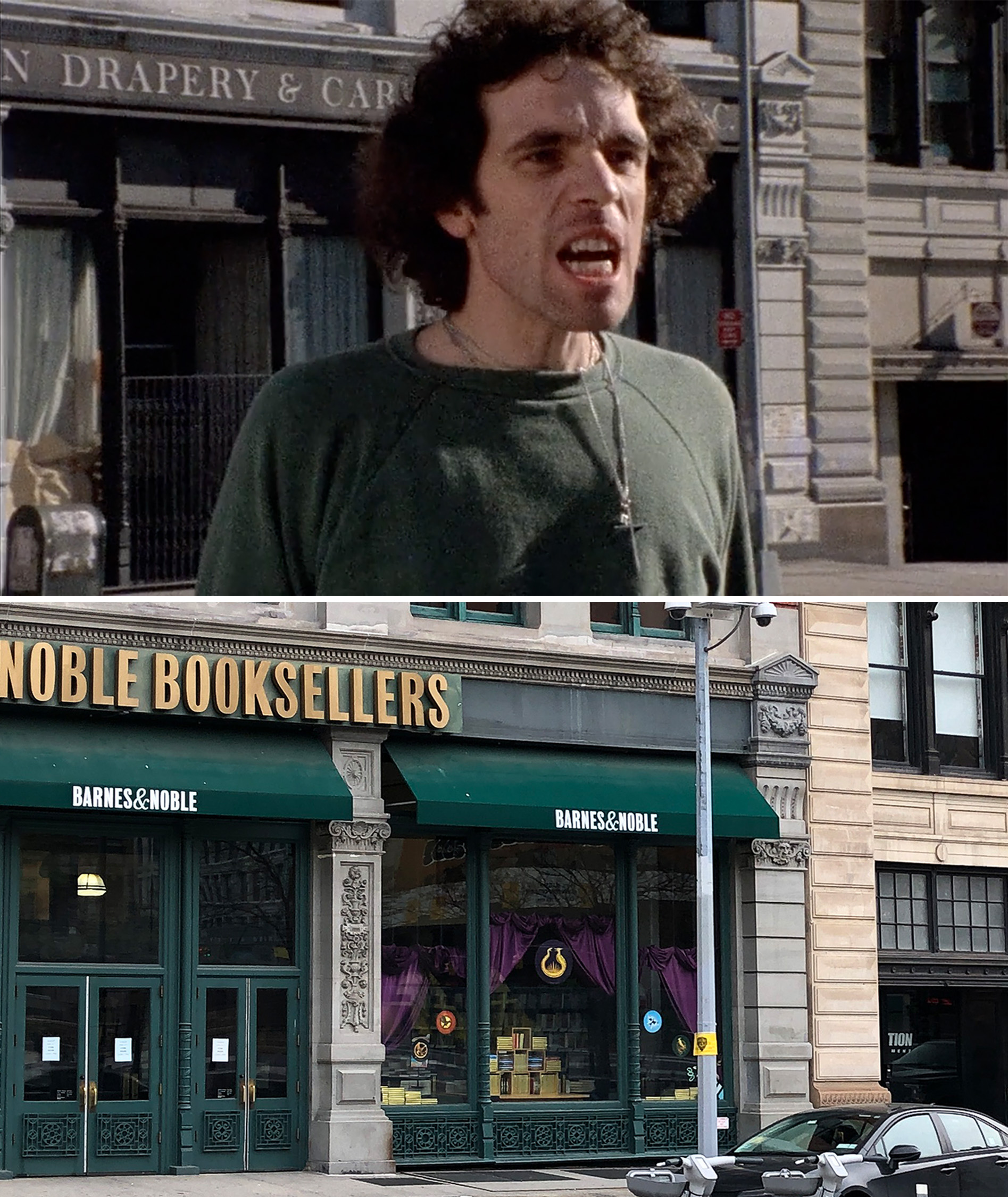

Based on the architecture and a comment made by Ferrara on the DDV audio commentary, I knew this hardware store was in the Union Square area, most likely on or near Fifth Avenue. There were a couple clues to go on, including a pair of signs on the neighboring building — one for a “Pillow Furniture Outlet Factory” and another for what looked like, “Jimmy’s Tailor.” Unfortunately, neither of those business signs netted me any promising leads.

Blakeslee eventually found this location by digging up a 1997 reference to a “B&N Hardware” on W 19th Street which he determined was the same one from the movie. I verified this by matching up the fire escape and neighboring buildings.

Amazingly, the hardware store was still in business up until around 2014. I’m glad we were able to find this location, but sad to see yet another mom-n-pop store fade away.

Subway Mayhem

A small disclaimer: even though I believe I established the basic area used for this subway scene, I could be off by a 25 feet or so. It was hard to find the exact spot because the Union Square Station has been remodeled and renovated since the seventies, including relocating some of the staircases.

But you get the gist of things.

Bus Stop Kill

There were many clues to help find this location. Right off the bat, I could tell the building behind the bus shelter looked somewhat modern —mid to late century— which meant it probably wasn’t in the Union Square/Flatiron area which has mostly older, Beaux Arts buildings. This was confirmed when I saw the bus that arrived at the stop was the M103, which runs along Lexington and Third Avenues. But I knew it had to be Third Avenue because in the movie, you can see two-way traffic, which only occurs on Third between E 24th Street and Coopers Square.

So basically, it had to be somewhere on Third Avenue between 9th and 24th Street.

First, I looked up old addresses of Sloan’s Supermarkets (whose sign can be seen behind the bus shelter), but I couldn’t find an outlet on Third Ave.

First, I looked up old addresses of Sloan’s Supermarkets (whose sign can be seen behind the bus shelter), but I couldn’t find an outlet on Third Ave.

So instead, Blakeslee and I just checked out every bus stop on Third Avenue between 9th and 24th Street in Google Street View to see if we could spot a matching building. But frustratingly enough, we couldn’t find it.

Turns out, the problem was the bus stops have switched around since the 1970s. Once that was figured out, we expanded our search and eventually zeroed in on the building at 196 Third. It no longer has a bus stop in front of it, but thankfully the facade has changed very little since 1979, including the air vents and service doors.

Midtown Killing

This scene was clearly not filmed in the Union Square area. Based on the view of the Empire State Building at the top of the scene, I figured it took place somewhere north of the iconic skyscraper on Fifth Avenue. My guess was it was somewhere in the high 30s, and I was able to substantiate this when I found a 1940 tax photo that showed a matching building near 38th.

Based on that tax pic, I estimated that the scene took place on the east side of Fifth, on the block between 38th and 39th. Since the ground floor facades have changed a lot over the years, it was hard to match up the exact building where the murder took place. But luckily, I could see a name on the glass next to Ferrara, which said “Ming’s.”

After a little poking around, I discovered Ming’s was a jewelry shop located at 435 Fifth Avenue.

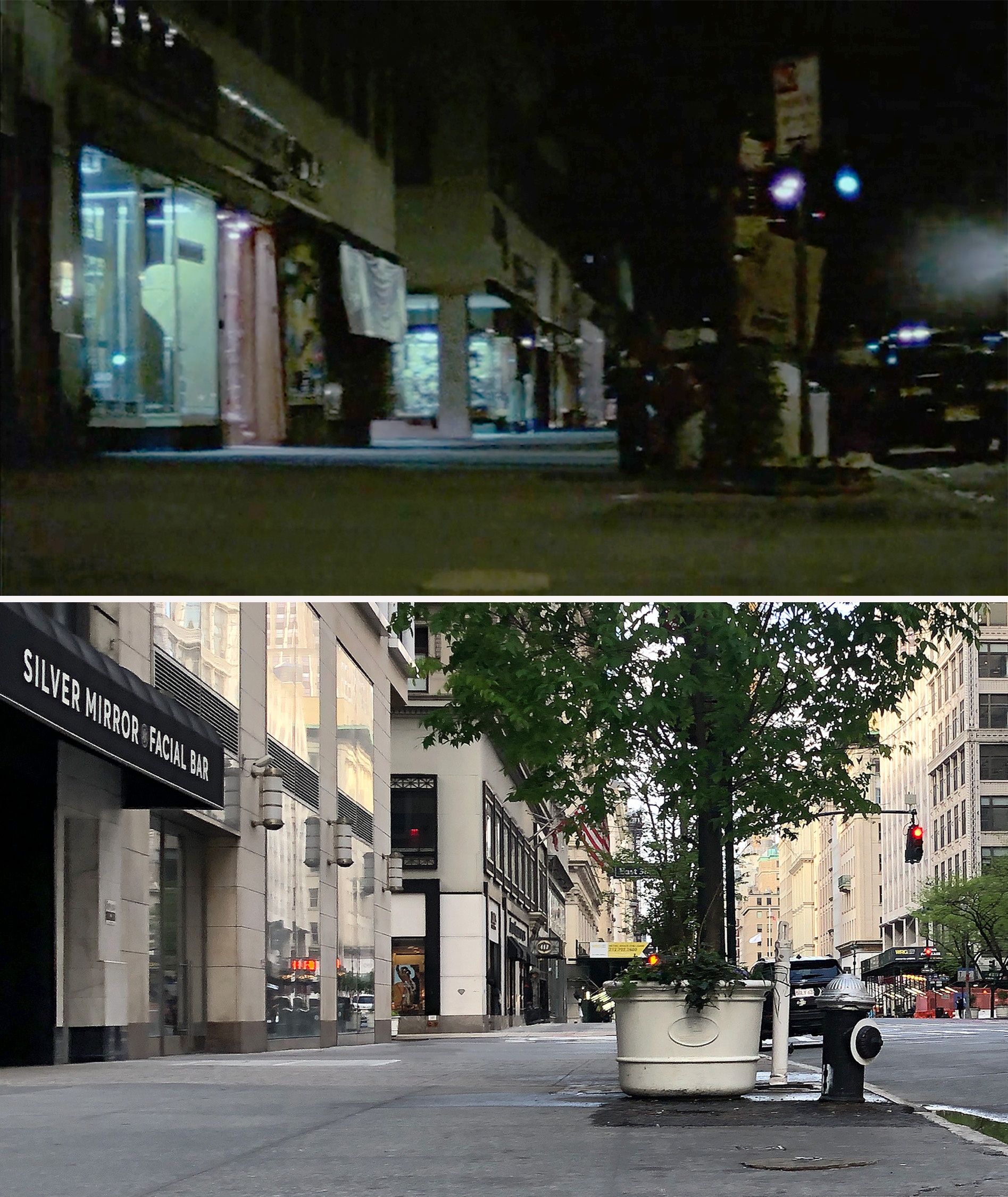

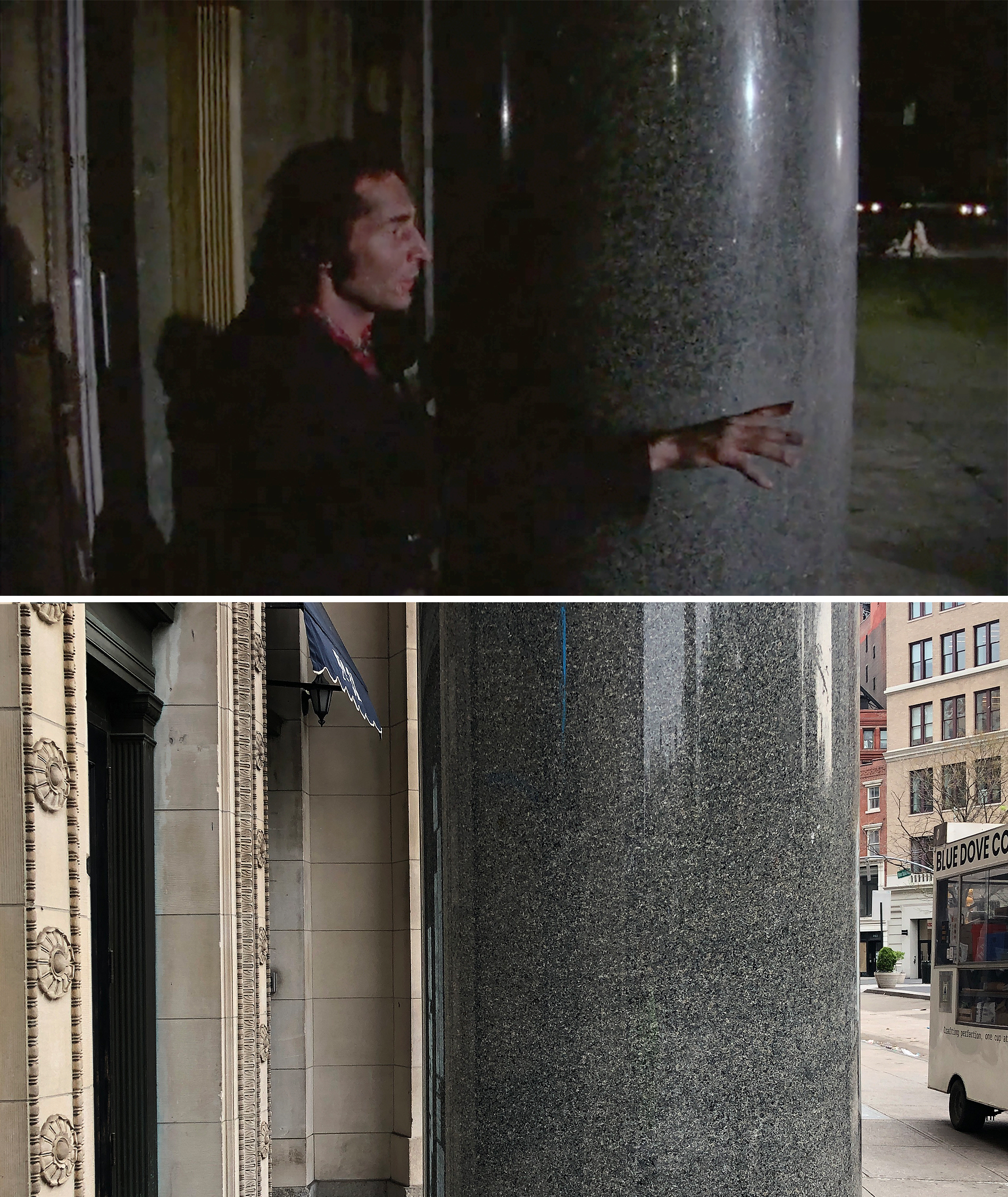

Murder Chase

Figuring this took place near Union Square Park, I just looked around the area until I found those distinct granite columns at 31 Union Square W.

I already had a feeling this scene was shot on that block, since you can briefly see a McDonald’s awning during the chase (which is still in business at that address today).

It might be noted that this scene contains the infamous “drill to the forehead” kill, which was featured on the cover of most of the home video releases. It’s been purported that the gory cover art is what helped put Driller Killer on the U.K.’s “video nasty” list, getting it officially banned in that country until the early 2000s.

I have to admit, it’s a pretty impressive special effect for a low-budge horror movie.

Phone Call

Again, this was found fairly quickly since it was located just northwest of Union Square Park. It was a little hard to confirm since the scene was shot using a long lens (compressing the image a bit).

But I was able to make a positive match-up with a building one block away at 114 Broadway.

Carol Walks Out

While Blakeslee and I were able to find the majority of the filming locations from this 1979 flick, there are still a few missing spots, but most of them are nearly-impossible to find without any inside information.

Even though I don’t love The Driller Killer, there are moments in it that are certainly very fascinating to watch. Not to mention, the movie serves as a nice time capsule of late-seventies NYC, especially since most of the folks that appear in the background are probably real New Yorkers going about their business.

And like I said before, I wholeheartedly acknowledge that there are people out there who are big fans of this bizarre urban slasher which helped launch the prolific career of director Abel Ferrara.

For many, Ferrara will forever be the master provocateur, filling his movies with tortured debauchery and blasphemous imagery. By their very nature, his movies demand a suspension of our accustomed expectations of the medium, which can be an unpleasant experience.

Admirers of Ferrara’s work give him the benefit of the doubt that the apparently chaotic storytelling and fractured characters are intentional aesthetic choices, designed to shake up our usual complacent presuppositions. And in the case of The Driller Killer, some film scholars see the drill not just as a weapon, but as a metaphorical tool used to invoke a visceral, unsettling feeling. In other words, the murder and mayhem is just a means to get to a bigger, more meaningful message.

This critical viewpoint could be summed up by a quote from famed economist Theodore Levitt, “People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!”

All that being said, I personally think Ferrara just likes making wacky and weird movies, and The Driller Killer certainly fits the bill. Bottom line, sometimes a drill, is just a drill.