This laid-back caper flick, adapted from Donald Westlake’s first novel in his Dortmunder series and directed by the versatile Peter Yates, may not be Robert Redford’s best movie, but it might be his most airy and amusing. Filled with light comedic touches and a dynamite cast of characters, The Hot Rock, is a wonderful Saturday-afternoon diversion, filmed entirely on location in the NYC area.

Unlike most movies of this genre, which rely on steel-trap plans executed with almost surgical precision, The Hot Rock is devoted to a perpetual comedy of errors, forcing its main characters to steal the rock-in-question over and over again. This unorthodox approach to the standard heist storyline seems to have also applied to its filming locations. By utilizing several unconventional and underused spots in the city, the filmmakers have created a brightly off-kilter version of the Big Apple that is almost otherworldly, diverging from the stark depictions often seen in the movies of this time period.

Released From Prison

When I first investigated The Hot Rock in 2016, there generally wasn’t as much info about filming locations on the web as there is today, especially for titles that weren’t blockbuster classics, like Star Wars or Back to the Future.

Fortunately, there was a smattering of info available on The Hot Rock here and there, mostly in the form of generic city names. On IMDb, there weren’t any specific addresses listed in their locations section, but it did include an entry for the village of East Meadow, which I deduced was where these prison scenes were shot.

The reason I came to that conclusion is because I actually filmed a Japanese TV show in the Nassau County Correctional Center in 2013, playing a wrongly-accused prisoner.

The main complex is a fully functioning detention center, but the older buildings to the south of it have been decommissioned for decades and serves as one of the go-to filming locations for movies and TV shows.

One key advantage to this Long Island facility is that it’s completely nonoperational, eliminating any security concerns, and thus, reducing the overall cost for a production (That’s why a fairly low-budget show like the one I was acting in could afford to shoot there.) Plus, being located in nearby Nassau County, it minimizes exorbitant travel time for any NYC-based production company.

However, ever since the former Arthur Kill Correctional Facility on Staten Island became a working filming studio in 2018, the demand for the Nassau County Correctional Center has waned a bit.

Driving Into the City

Tracking down these highway shots was fairly easy, especially with Calvary Cemetery being visible in several shots. Luckily, not much has changed in this part of Queens, making it easier to match things up. However, it does appear the Long Island Expressway has been widened a bit since the seventies.

Also, as you can see in the first “then/now” image above, a noise barrier has been added to the expressway, but the houses behind it are still there and relatively unchanged.

Reconnaissance at the Museum

Meeting Dr. Amusa

Every movie takes you on a journey —sometimes good, sometimes bad— and one reason why I’m so drawn to the exploration of NYC filming locations, is that the process takes me on a whole other journey that goes beyond a movie’s plot or its characters. It often becomes an experience in and of itself, with a whole different set of memories and rewards.

My memories of exploring The Hot Rock is of particular interest, as it was one the first films I chose to do a deep dive into its locations. This is going back around ten years ago where a lot of the tools I use today were either unavailable or unknown to me. And even though I’ve lived in New York since the late 1980s, once I began this mission to search out filming locations, I quickly recognized that I didn’t know the city as well as I thought I did.

Case in point: this park scene. I was both intrigued and perplexed by the curious little setting, taking place on a wide pathway, surrounded by exposed bedrock and rust-orange benches (opposed to the traditional green), and feeding directed into city streets. Nothing about the park looked familiar, and even though I was certain it was somewhere in NYC, it almost looked like a Hollywood recreation. And the basketball court only bolstered my befuddlement. The court’s rear wall was the base of an elevated promenade, which in turn bordered a clear, open sky vacant of any buildings, giving us the impression we were on some coastline precipice or floating on a distant cloud.

Having said this, I felt there still were a couple decent clues in these scenes that could help me find its location — there was an unusually wide park entrance showing several large apartment towers on the nearby streets, and the open sky at the basketball court indicated they were probably situated along one of the rivers. Frustratingly, even with these clues, I wasn’t able to figure out what park had been used.

It was then that I decided to ask my college buddy, Blakeslee, to see if he could help out. This, I believe, was the first time I ever asked him for assistance in finding a movie location, but it quickly developed into a long-standing collaboration that still continues today.

One good thing about having a research partner is sometimes they come up with different approaches to a mystery — and in this instance, that’s just what Blakeslee did. Instead of focusing on the park itself, he zeroed in on the buildings on the adjacent streets, eventually identifying the corner townhouse at 140 East End Avenue. He recognized the distinct and quaint redbrick building to be part of a small (approximately a half an acre) assemblage of contiguous homes built on the Upper East Side in the 1880s, called Henderson Place.

I was thrilled Blakeslee was able to help me figure out this park location, although in retrospect, it wasn’t a terribly challenging mystery. But this was done in 2016, when he and I were still getting the feel of things. Back then, identifying any filming location, no matter how simple or small, was a triumphant event, summoning up a tremendous feeling of exhilaration.

Kelp’s Store and Apartment

Finding this pair of locations proved to be much easier than the park. On the lock shop’s front door, there was the number 682, which I hoped was a real address and not set dressing. After checking out that number on a few avenues, I soon determined the shop was at 682 Columbus.

It was a little hard to match things up since the ground level of this Mid-Century Modern building has since been augmented with an ornamental facade, including clapboard wood siding, a pitched roof with dormer windows, and a white-picket fence. However, I was able to verify this location by lining up the large apartment high-rises that appear in the background.

The retail space has gone through several different ownerships over the years. Back in 2015, it was a steakhouse. When I took my photos in 2019, it was a restaurant called Elizabeth’s Neighborhood Table. But it soon closed down, and about a year later, it became New Amsterdam Burger.

Then, right before I started writing this post, I returned to 682 Columbus Avenue to take some new pictures, only to discover that the burger restaurant had closed as well. Like most restaurants in NYC these days, unless you’re extraordinarily popular, it’s nearly impossible to sustain a profitable business, especially when dealing with the city’s notoriously high rents. So, I will just have to wait and see what moves in there next before I bother to take a new picture for this website.

Anyway, after finding the lock shop location, it quickly led me to finding the apartment location, which was only one block away. Confirming the apartment could’ve been a little tougher had I been working off the 2018 BluRay release of the movie, because for some reason, on that transfer, the scene outside the apartment building was inexplicably flipped.

You can tell something’s amiss by the parts in Redford’s and Segal’s hair which jump from their left sides to their right, from one scene to the next.

Stan Murch’s Home

The thing that helped me find this location was the big highway next to the Murch household, which I suspected was the Long Island Expressway. As you can see in the first “then/now” image above, the expressway does a backwards S-curve not too far from the house. So I just looked on a map for any curves that could fit the bill, ignoring any areas that didn’t have a residential street paralleling the LIE.

With that specific criteria in mind, I soon landed on 55th Drive. And even though the Murch house has changed since the seventies, I confirmed the location by matching up several buildings on the other side of the expressway.

And by the way, if you’re a fan of 1980s sitcoms, you might’ve noticed the woman portraying Murch’s mother was Charlotte Rae, best known for playing Mrs. Garrett in Diff’rent Strokes and it’s spin-ff, The Facts of Life.

The Bar

This was figured out through the help of the New York Public Library on 42nd Street, which has a century’s worth of phone directories on microfilm. I could see from the neon sign outside the bar that it was called McGlade something, and I assumed it was a real place.

After searching a 1972 directory, I found a listing for a McGlade & Ward at 485 Columbus Avenue, just south of W 89th, which was not too far from the Kelp lock shop location. However, I still wasn’t fully confident I found the right place, partly because different versions of McGlade’s seemed to have appeared in several different addresses on the Upper West Side.

Adding to the difficulties in confirming this location, the building at 586 Columbus Avenue, along with all of its neighbors, got torn down decades ago. It wasn’t until the NYC Municipal Archives released the 1940 tax photos a few years later that I was able to match up several of the old buildings, including the one on the northwest corner of W 89th Street.

Finally certain I got the right bar, I did a little further investigations into the block and discovered that the building at no. 586 was actually used for the interiors of Travis Bickle’s apartment in the 1976 movie, Taxi Driver.

You can even see the same bar (but with a different name) in a promotional photo they took outside the building — an image that became the inspiration for its iconic poster.

Testing Out Explosives

This was the very last location I figured out for this movie, solving it only a couple weeks ago.

When it comes to rural settings like this one, unless I can find contemporaneous production notes/call sheets, or an interview with a cast or crew member who gives out specific details, the likelihood of me discovering its location is usually pretty slim. Over the years, I had halfheartedly tried to figure out what lake was used in this scene, but it wasn’t until I heard the news of Redford’s passing that I became more determined to find it.

By pure luck, I happened to be recently studying the filming location of the farmhouse in the 1976 movie, Network, which turns out, was located not too far from this lake. I figured this out when I noticed a similarity in some bluffs in the background.

Excited, I quickly compared screenshots from both movies and was able to successfully line up the rocks and ridges in the outlying bluffs.

They’re actually part of the Palisades Cliffs that run along the Hudson River, and we’re looking inside the Haverstraw limestone quarry which was blasted open, starting around 1927.

Then, after figuring out the general area where this scene took place, I zoomed in on a map of DeForest Lake (which is actually a manmade reservoir created in 1956 by damming the Hackensack River), figuring out where exactly the scene took place. In the movie, you can tell they’re near a small inlet, and the only inlet in that part of the lake is about a quarter of a mile from the Network farmhouse, along route 304.

I was incredibly excited that I found the right spot and was very eager to go there in person to take some pictures. Only problem: I don’t have a car. So, I ended up taking a PATH train to Hoboken, where I picked up the NJ Transit to Spring Valley, NY, and then walked the 8 miles to DeForest Lake in Congers. And of course, that meant I had to walk the 8 miles back to the train station in Spring Valley.

I also took a couple side trips along the way to visit some other filming locations, including the police station from the 1989 movie, Family Business. In the end, I walked about 2o miles that day, and as tiring as it was, it was a pretty fun way to spend an autumn afternoon.

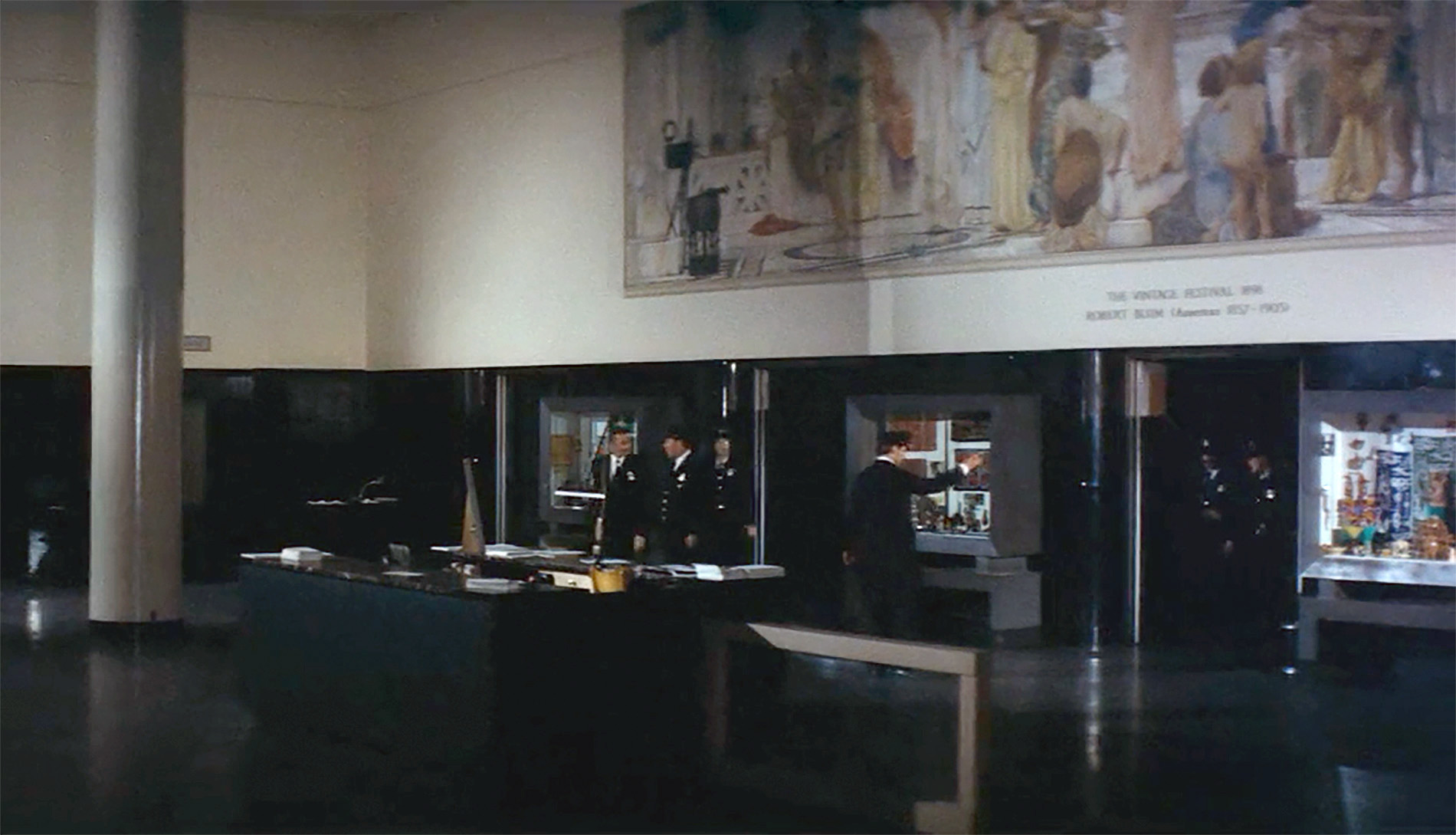

Museum Robbery

This is one of those locations that was pretty obvious to identify (Roger Ebert even mentions the museum by name in his 1973 review), but when I first saw this movie some 15-20 years ago, it seemed like a place from some other city. It’s a location that appears to be part of an intentional pattern by the filmmakers to use places that aren’t typical for NYC movies. Normally, you’d expect something like the Met or the Guggenheim to be the featured target, but by choosing the Brooklyn Museum, it shakes up our expectations and helps create a more offbeat urban landscape.

Founded exactly 200 years ago, the Brooklyn Museum has NYC’s second largest art collection, amounting to over 500,000 objects. And the museum’s neoclassical building is a bit of an art piece itself, containing the magnificent Beaux Arts Court where most of the movie’s action took place.

Designed by one of the city’s most prestigious firms, McKim, Mead & White, the main building was completed in 1897, although it’s been expanded several times over its lifespan.

The most obvious addition to the building, as seen in the exterior “then/now” images above, is its front entrance. This happened from 2000-2004 when museum officials hired architect James Polshek to design a new $63 million, glass-clad entrance for the building. (There was some opposition from local preservationists).

While there’s nothing wrong with it, I’m not sure exactly how much value the glass atrium added to the museum’s appearance, especially in light of its hefty price tag.

The changes to the building also made things a little harder for me to line up my “then/now” images. Not just for the exteriors, but also for the lobby area, which now looks very different from the movie.

The open stairwell is no longer there , nor is the giant mural above the doors, but fortunately, the large cylindrical post is still standing, helping me get my bearings for my modern photo.

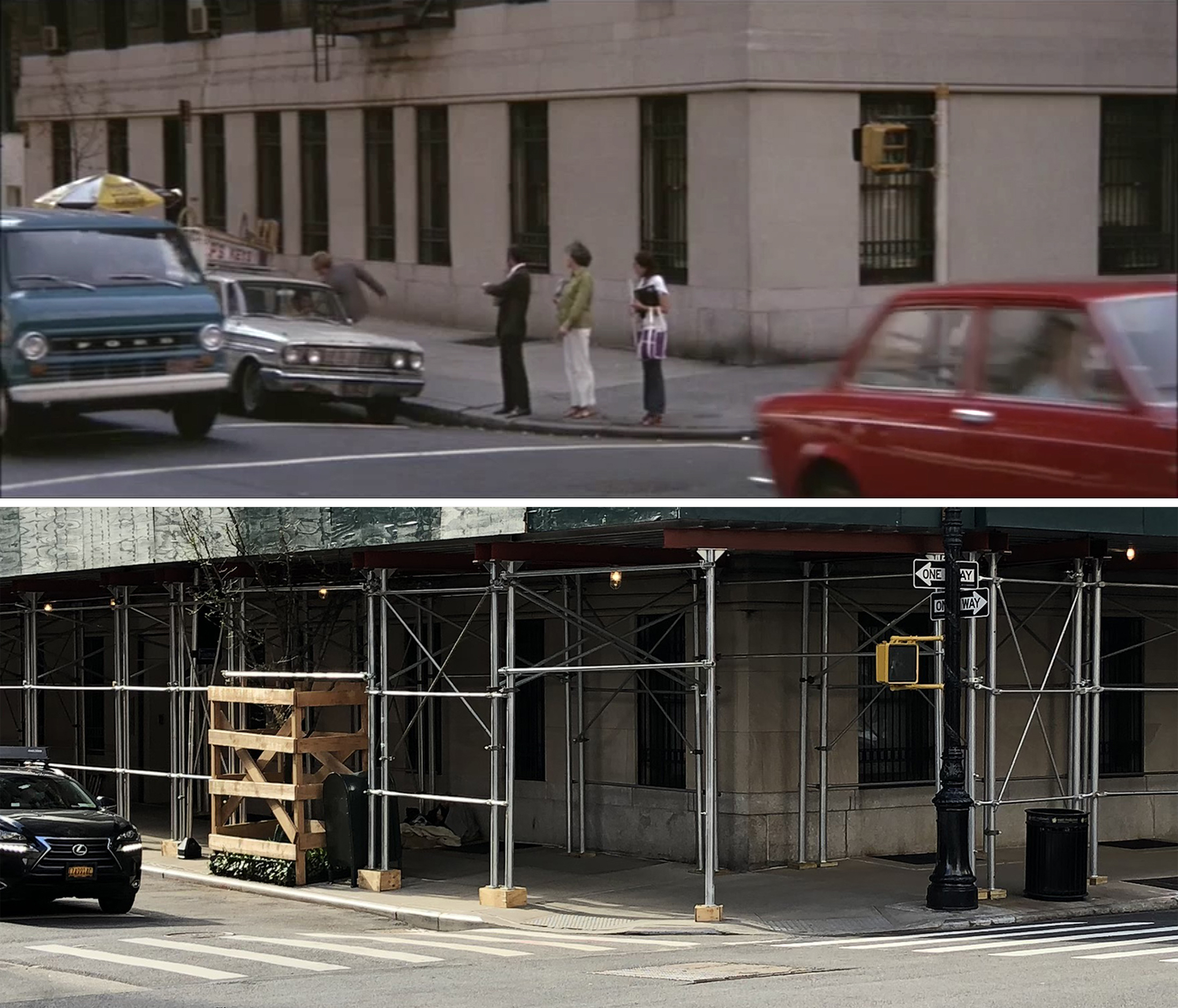

With all these changes to the front of the museum, it didn’t affect the staff entrance where Dortmunder and Kelp stage a fake mugging. That’s because it was filmed at the central branch of the Brooklyn Library just down the parkway. As soon as I studied the scene, I knew it had to have been filmed somewhere else because the residential buildings that appear in the reverse angle didn’t match anything that’s around the museum.

Unfortunately, the library is currently undergoing some renovations, causing a partial obstruction of the filming location, but you can still see the matching staff doors and even the same specks in the stone panel above them.

Sadly, the Brooklyn Museum has lost a lot of its revenue over the last decade or so, forcing them to lay off a large chunk of their staff. It’s a shame, because it has quite an impressive collection of art and artifacts, and has the benefit of being located right next to the Brooklyn Botanical Garden, which is the paragon of loveliness and serenity. Overall, it’s well worth a visit, and by being a little off the beaten path, it can be a nice diversion from the hustle and bustle of Manhattan’s Museum Mile.

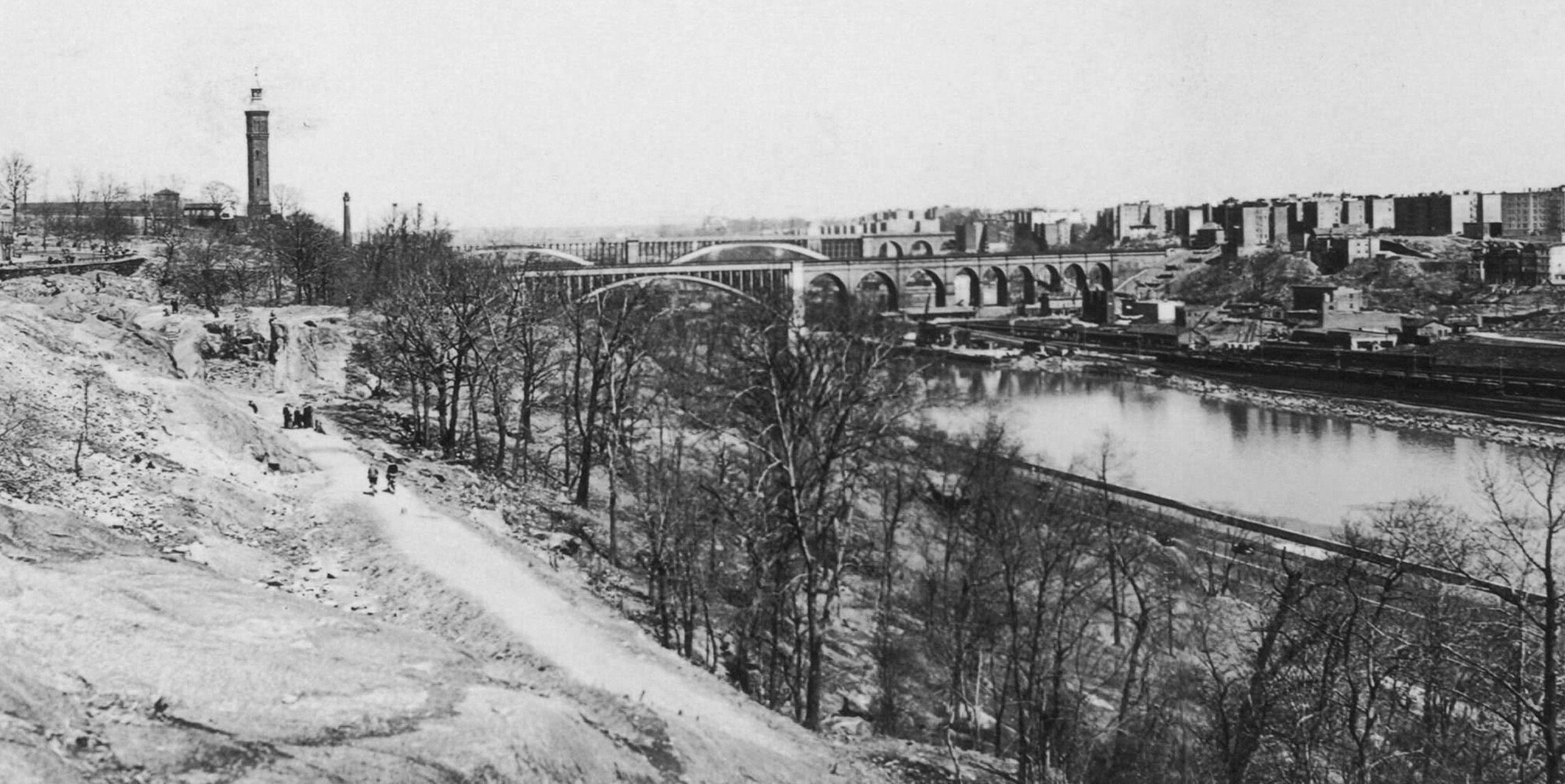

Meeting Greenberg’s Dad

This wasn’t necessarily a hard location to figure out, as there were several clues to work from, including the park’s distinct, 200-foot-tall water tower jutting from the river bank. The interesting thing is, I had no knowledge of Highbridge Park when I first began my investigation into this movie ten years ago. I’ve since become much more familiar with this Washington Heights park, along with its octagonal tower, and its steel arch bridge that stretches across the Harlem River into the Bronx.

The park derives its name from NYC’s oldest standing bridge, the aforementioned High Bridge, established in 1848 as a part of the Old Croton Aqueduct.

The cliffside park was developed in the late 19th century, and continued to expand in size over the next few decades. Appealing to upper-middle class New Yorkers, the park offered wide boardwalks for well-dressed Manhattanites to stroll upon, and acres of rolling hills for kids to frolic in. For more entertainment, folks could head to the north end of the park which was home to Fort George Amusement Park.

During its early years, the park’s main attraction was most certainly the Harlem River Speedway situated along the riverbank. It was here that visitors could watch horse and carriage races along the track, as well as boating competitions on the Harlem River.

At first, use of the speedway was restricted to equestrian travel, theoretically reducing the amount of menacing road traffic with other vehicles. In particular, bicycle riding was singled out, being prohibited from the speedway in no uncertain terms. This is evidenced in a 1898 New York Times article written just prior to the track’s opening, where it unabashedly declared: “No Danger that Bicyclists Will Mar the Horsemen’s Sport on the Speedway. THEY ARE EXCLUDED BY LAW.”

By the 1920s the Harlem River Speedway was paved and open to motorists, eventually being developed into the Harlem River Drive that exists there today.

In addition to horse and boat racing, Highbridge Park has a connection with another sport — baseball.

From 1890 until 1964, the park’s southern bluffs overlooked the Polo Grounds, a stadium that served as the home field to the New York Giants. It was also the temporary home of the Yankees before their Bronx stadium opened in 1923, and the Mets for two years before they moved to Shea Stadium in 1964. The site was cleared that same year and is now the location of a low-income housing complex called Polo Grounds Towers.

These days, Highbridge Park is a little shabby and not particularly popular, but it is definitely in better shape than it was in the seventies when this movie was being made. Once again, it was a bold, unusual choice by the filmmakers to shoot this scene in Highbridge Park, opposed to something more conventional like Central Park.

The United Nations

Breaking Greenberg Out

As I mentioned earlier, information on this movie was scarce back in the 2010s when I was researching it, but I did manage to find a Long Island message board that discussed this filming location in East Meadow. It’s usually hard to confirm these types of shopping centers since the businesses and the buildings will have gone though many changes over the years. But it certainly made logical sense that they filmed at 1980 Hempstead Turnpike since it’s less than a mile from the Nassau correctional facility.

When I finally visited the plaza in person, I was pleased to see that the layout looked correct. Plus, when I checked out the back area, the building that was a bank in the movie was virtually unchanged, convincing me that the folks on that message board were correct.

Meeting with Amusa Again

I found this location through a simple process of elimination. They were clearly on a river, and judging by the land on the other side, we were looking across the Hudson towards New Jersey. You can also see a distinct tower protruding from the Jersey shore, so I just virtually traveled up the river in Google Earth until I found what looked like a match. Then I checked out the Manhattan side and zeroed in on the boat basin at 79th Street.

The boat basin, which is located within Riverside Park, was first developed in the 1930s, as part of parks commissioner Robert Moses’ plan to improve the area and provide a parking garage for local residents. It was constructed as a three-level concrete and masonry rotunda, functioning on its upper level as a traffic circle for the Henry Hudson Parkway. The plaza-level arcaded rotunda was created in conjunction with the boat marina on the water, offering services to floating vessels parked along the long stretch of docks.

It’s one of a few publicly owned and operated marinas within the five boroughs and is the city’s most heavily-subscribed marina, although it’s currently closed as it undergoes repairs.

Luckily, I was able to take the modern photos of this location just before the area was closed off. The space was home to the Boat Basin Cafe at the time, but they were forced to move out when the repairs began. Once completed, the city has announced that they’ll let restaurant operators bid on the property — which is now reportedly reserved for fine dining venues.

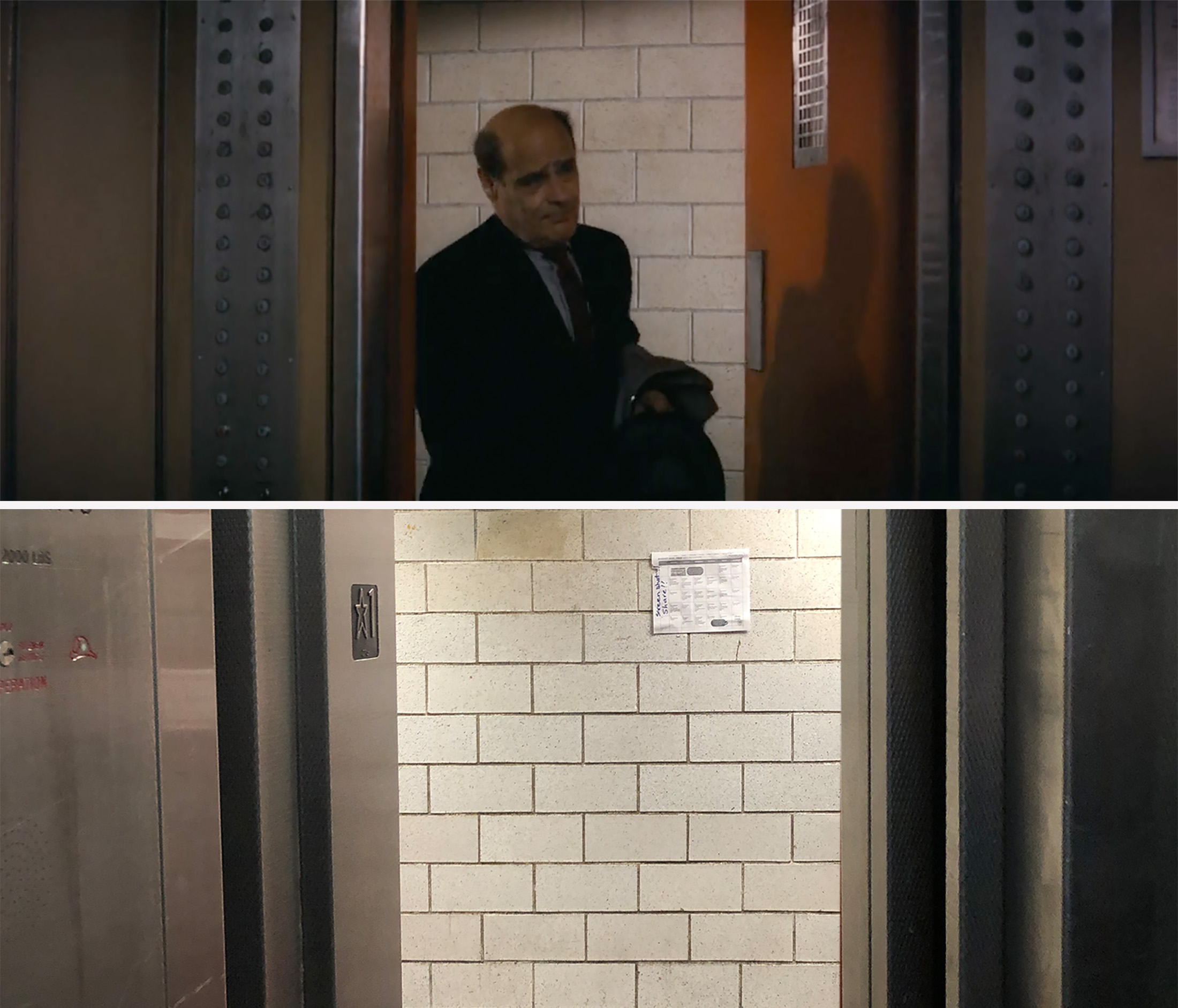

Scoping out the Police Station

While finding this location seems like an easy task these days, it took me some time to find it back in 2016. I basically spent hours searching Google Maps in 3D mode, trying to find matching buildings based off the helicopter footage used in a later scene that also takes place there.

There have been a few changes to the buildings along that block, but the police station, which is now a condominium building, looks relatively the same. And I was delighted to see that the entrance at 128 Charles, where Redford once stood, still has the same wood frame around it.

Back to the United Nations

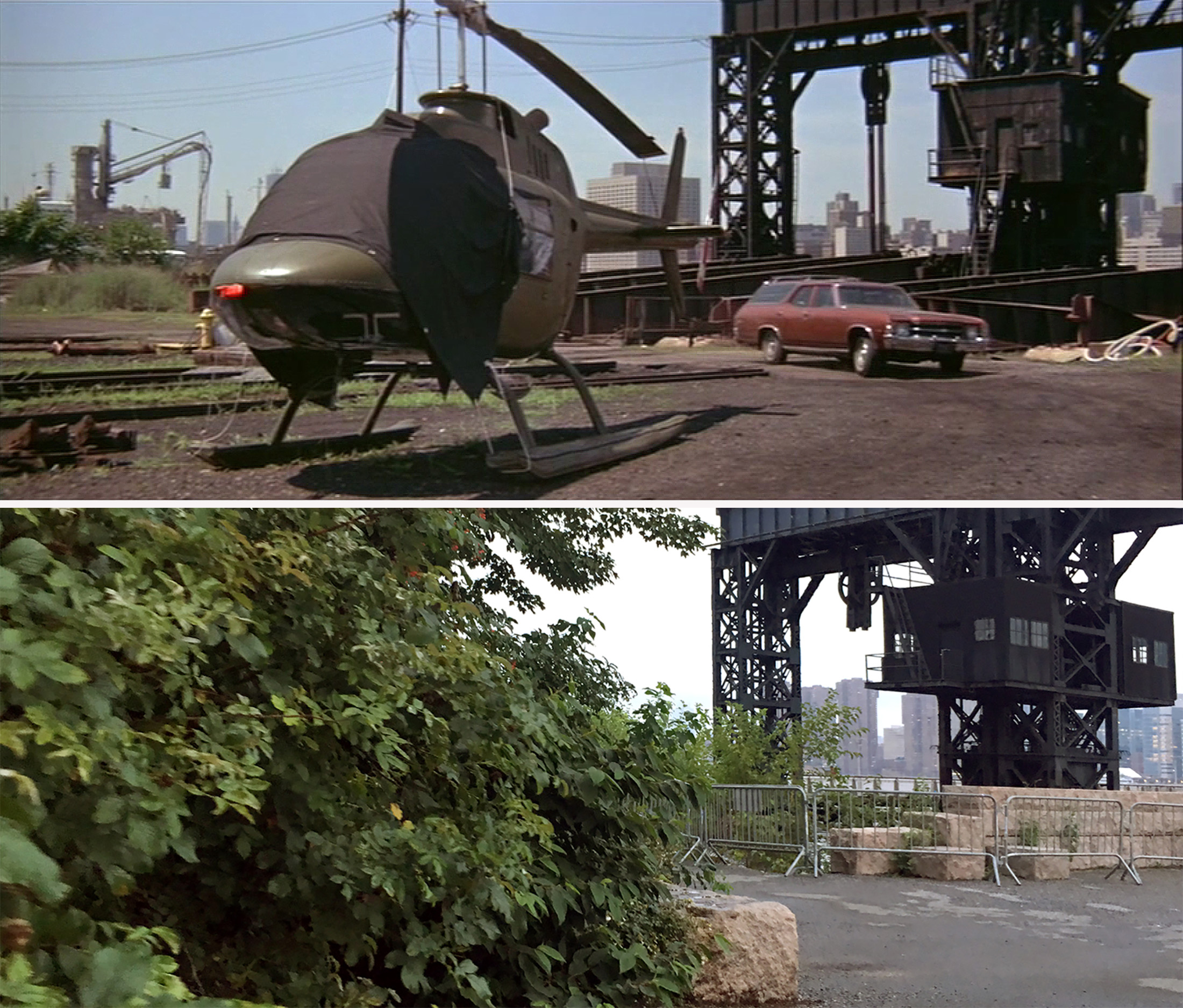

Flying a Helicopter

Attacking the Police Station

As I said earlier, these helicopter shots are what helped me find this police station location. Of course, one of the more poignant helicopter shots is that of the WTC towers being built. You can’t help but get an unnerving feeling seeing any sort of flying device so close to the towers, even if it’s just a helicopter thirty years prior to 9/11. But aside from that, it’s interesting to see how much taller the landscape has gotten in Lower Manhattan these days — and this upward growth doesn’t seem to be abating.

Even the West Village has seen more towers creep into its neighborhood, but luckily most of the smaller period buildings have remained intact. This includes the Beaux Arts police station on Charles Street, dating back to 1896 when it served as the 9th Precinct. The precinct was renumbered several times after that, finally becoming the 6th Precinct in 1929. The station remained the 6th into the sixties, ending with the department becoming infamously involved in the Stonewall Riots.

On June 28, 1969, riots and demonstrations erupted on the streets after police from the 6th precinct raided the Stonewall Inn, a known gay establishment, which was interpreted by locals as police persecution. The week-long event has been cited as a significant impetus for the gay rights movement in America, commemorated every June with the New York pride parade.

Shortly after the riots, the 6th Precinct moved out of the Charles Street Station, leaving the building empty for several years. It was during this time that they shot these scenes from The Hot Rock. And if you look closely, you might notice that comedic writer/director/performer Christopher Guest has a small part as a police lieutenant (played with goofy aplomb).

A few years after this movie was made, the old police house was sold at a public auction to Yugoslavian-born contractor Slavko Bernic for $215,000. The building was gutted, redesigned and reopened as an apartment house in 1977 named, “Le Gendarme.” .

These days, a one-bedroom there goes for about $4,000 a month, and just in case you’re wondering, is completely bereft of any hidden gems.

Scoping Out the Bank

Coming Up with a New Plan

This is one of those exterior locations that looked familiar —a two-way street with high-rise apartments leading into an open sky is a very specific configuration— but it took me a little time to recall where it was.

Having biked all over the city, there are certain areas that get more traveled than others. And even though I couldn’t quite place it, I had a strong feeling I had been there before. In the meanwhile, I tried another more basic tactic. I tried to see if I could find an old listing of an Esso gas station, seeking out an address for the one that appears up the street from Amusa’s high-rise. But I couldn’t find anything that made sense.

Finally, out of the blue, it just hit me! That two-way street was York Avenue, and its northern end sort of just merges into FDR Drive along the East River (hence the open sky). It’s all part of a biking route I used to take if I wanted to travel between Manhattan and Randalls Island (whose foot bridge is about ten block to the north).

Once I determined that the exteriors were shot on York Avenue and E 89th Street, I could tell the interiors were shot somewhere else. The buildings seen out the window lent to the environs of Midtown Manhattan, so I just did some roaming around, looking at the skyscrapers, eventually finding some matches along Sixth Avenue in the low 50s.

Then, judging by the vantage of the neighboring buildings, I determined they were on one of the upper floors of the Hilton hotel at 1335 Sixth Avenue.

Then, judging by the vantage of the neighboring buildings, I determined they were on one of the upper floors of the Hilton hotel at 1335 Sixth Avenue.

And I gotta tell you, when I went to the hotel in person last week, the folks were super nice, especially Brian, the Senior Sale Manager with Hilton Grand Vacations. He seemed genuinely interested in figuring out where exactly the action took place in the hotel, and shared some fun facts he learned during his 20 years with the company. With just shy of 2,000 rooms, the Hilton Midtown is the second largest hotel in NYC, and certainly one of the busiest. Over its years, it’s been a favored sojourn for several celebrities, including Lucille Ball, Elvis Presley, Robin Williams, and John Lennon (who wrote the lyrics to the 1971 song “Imagine” on hotel stationary while staying there).

When the hotel was being constructed, it went up directly to the east of the Adelphi Theatre, best known for being the stage where Jackie Gleason filmed the 39 classic episodes of The Honeymooners. The Adelphi was torn down in 1970 and was eventually replaced with an office tower that connects to the Hilton with a walkway.

The sales office on the west side of the 45th and 46th floors is where Conrad Hilton’s private duplex residence used to be. It still has a lot of the original fixtures from when the hotel first opened in 1963, including a fireplace and spiral staircase.

You can get a glimpse of what the penthouse looked like back then in a 1963 episode of Candid Camera, recorded shortly after the hotel’s opening.

Even though the office layout resembles what appears in The Hot Rock, it’s actually on the opposite side of the building from where they filmed this scene, Normally, that side of the building is only accessible for guests of The Residences staying in the penthouse suites, but Brian was kind enough to take me there so I could take a few photos.

The modern photo in the first “then/now” image above was taken in the private lounge on the 44th floor which offered virtually the same window view as the movie, but was just one floor lower.

However, if you want to be exactly where the scene took place, you’d have to book the one-bedroom penthouse suite at the southeast corner of the 45th floor (which, according to the website, goes for around a grand a night). The floorspace has obviously been subdivided into modern rooms, and the spiral staircase and fireplace are now gone, but the same balcony is still there (along with its southern views).

Getting Double-Crossed

Hypnotizing the Bank Employee

Blakeslee helped me find this apartment building. I could tell it was at some Manhattan public housing complex, but couldn’t figure out which one. In general, these complexes are fairly easy to find on a map, as they tend to take up multiple city blocks. However, finding the right one can sometimes be a lengthy task, and occasionally one can slip past your radar.

The problem is, many of these mid-century housing developments look a lot alike, usually with similar sizes and colors. But each development will have a few subtle differences in the buildings, such as their window arrangements, whether they have balconies or not, or how they’re positioned in relation to the streets. So you’ll often just have to go through them, one by one, looking for these specific differences.

In this instance, Blakeslee and I were both going through the process, and he simply ended up hitting the target first. He was also able to quickly confirm the location by identifying the school that appeared in the background.

Sitting on nearby W 102nd Street, the school was PS 179, aka, West Side High, which was replaced in the late 1990s with a 3-story modernist-style school.

Back to the Bank

This bank location was easy to find since you can clearly tell it was on Park Avenue and you can see the distinct Racquet and Tennis Club Building (EST 1918) catty-corner to it. Getting modern photos inside the building wasn’t such a straightforward task, especially in the basement-level where the safe deposit boxes are secured.

I ended up getting access to this area by posing as a potential bigwig customer, then snapped a few surreptitious pics as the bank employee was retrieving a sample box from the vault.

Even though they’ve since walled-in what was anon space in the 1970s, I was thrilled to see a lot of elements still intact, such as the vault door, the floor pattern, and the staircase.

Since all the ensuing shots after Redford leaves the bank were captured on Park Avenue, it wasn’t too hard to find the exact spots used. It just took a little looking around, and since a lot of buildings on Park are unchanged, it was easy to confirm. It’s a nice way to end my investigation into the filming locations of The Hot Rock.

Lightweight and family-friendly, The Hot Rock mostly succeeds as a fun caper flick thanks to Robert Redford’s effortlessly charming performance.

Sandwiched between Redford’s more recognized thievery movies —Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and The Sting— The Hot Rock has ended up being mostly forgotten. (I hadn’t even heard of it until the mid-2000s.) But like a lot of his movies during this period, it’s hard not to like it, even with some of its more ridiculous moments.

I personally like it because it takes the blueprint of a swell-oiled heist movie and spins it on its ear. Based on a popular series by Donald Westlake, the script was adapted by William Goldman, who would later pen two of my other favorite seventies movies, Marathon Man (1974) and All the President’s Men (1976).

The storyline is certainly fun, but it’s also fairly farfetched, but it’s made more believable by the cast of competent supporting actors. George Segal, Ron Leibman and Paul Sand all give distinct performances as Dortmunder’s band of criminal misfits, and Zero Mostel is used the appropriate amount as Greenberg’s overzealous and conniving father.

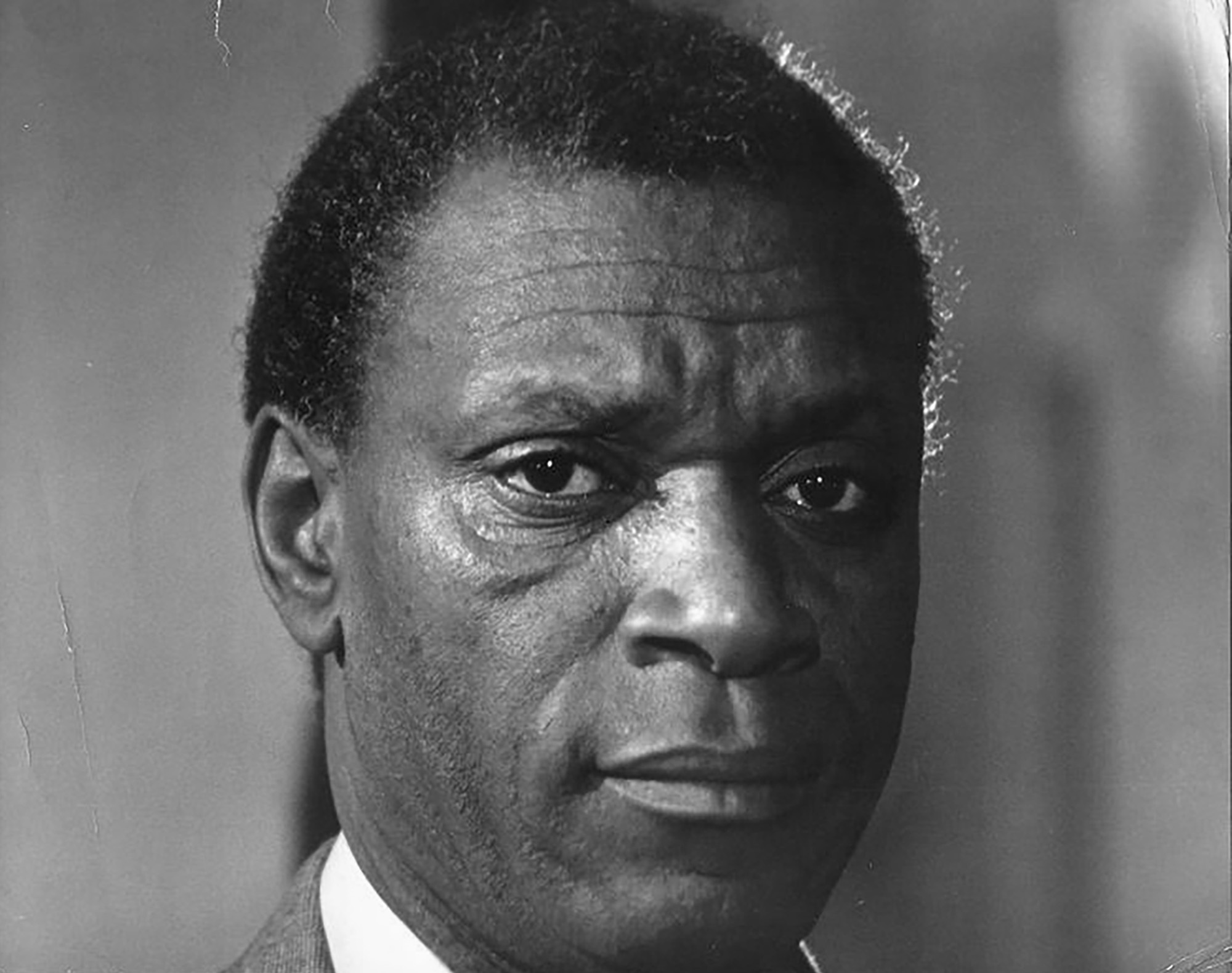

Anchoring the cast of scatterbrained characters is Dr. Amusa, who becomes the embodiment of exasperation, played with cool dignity by Moses Gunn.

Tying all this material together is British director Peter Yates, who keeps the story moving at fast pace, never lingering too long on a plot point to allow us to realize its absurdity. Like most of his work, there’s a certain glossiness to this movie, and it’s reflected in the beautiful photography, conjuring up a vivid and unique version of NYC.

As a whole, The Hot Rock might not resonate the same way Redford’s more famous NYC seventies flick, Three Days of the Condor, does, but it’s still a worthy entry into his expansive filmography.

Inventive and ambitious, this movie goes down with relative ease, and cutting through all its shenanigans is a singular vision of rakish urbanity. And I must say, it’s refreshing to see such an effervescent depiction of the Big Apple in an era that was generally filled with grit and grimness.