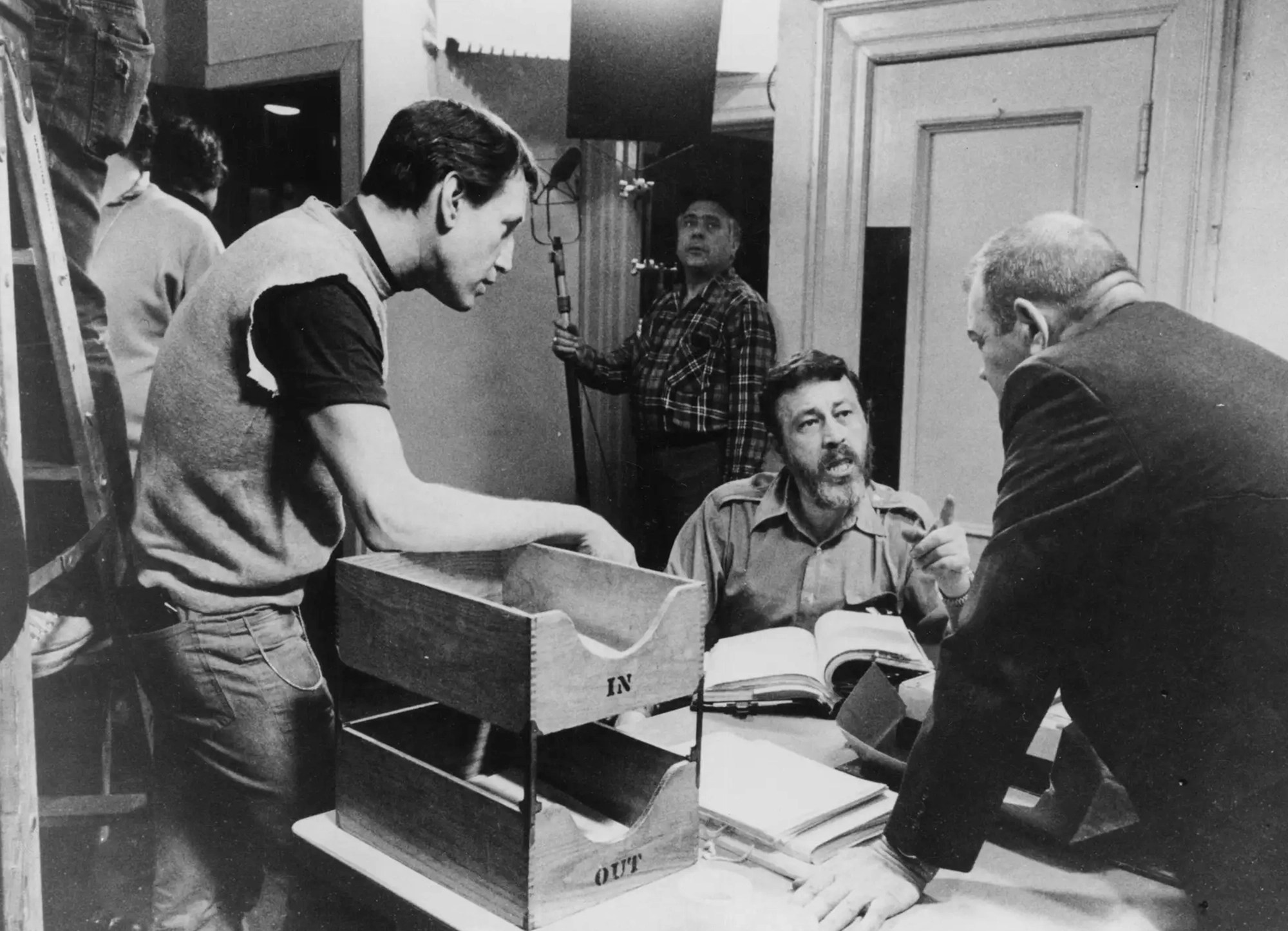

A 1970s action film most people have never heard of, The Seven-Ups is a riveting cop thriller that some have called the spiritual sequel to 1971’s The French Connection. It was directed by French Connection’s producer, Philip D’Antoni (his sole directing credit), has many of the same cast and crew —including technical advisor, NYPD detective Sonny Grosso— and once again takes place on the streets of New York.

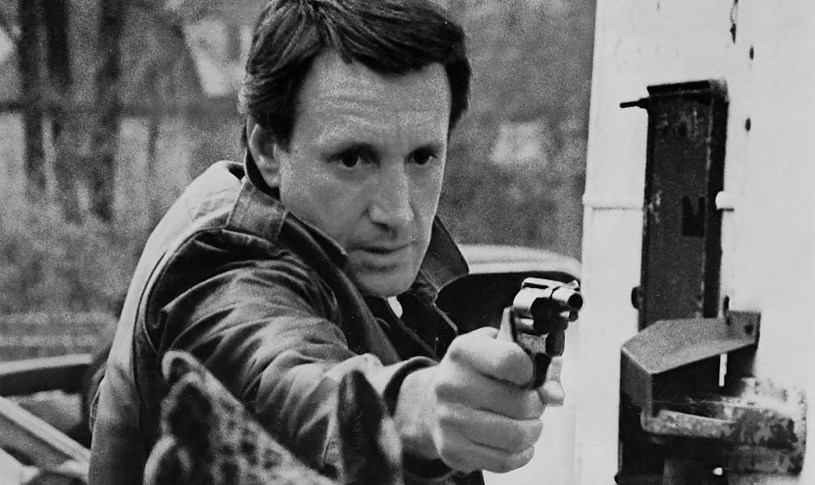

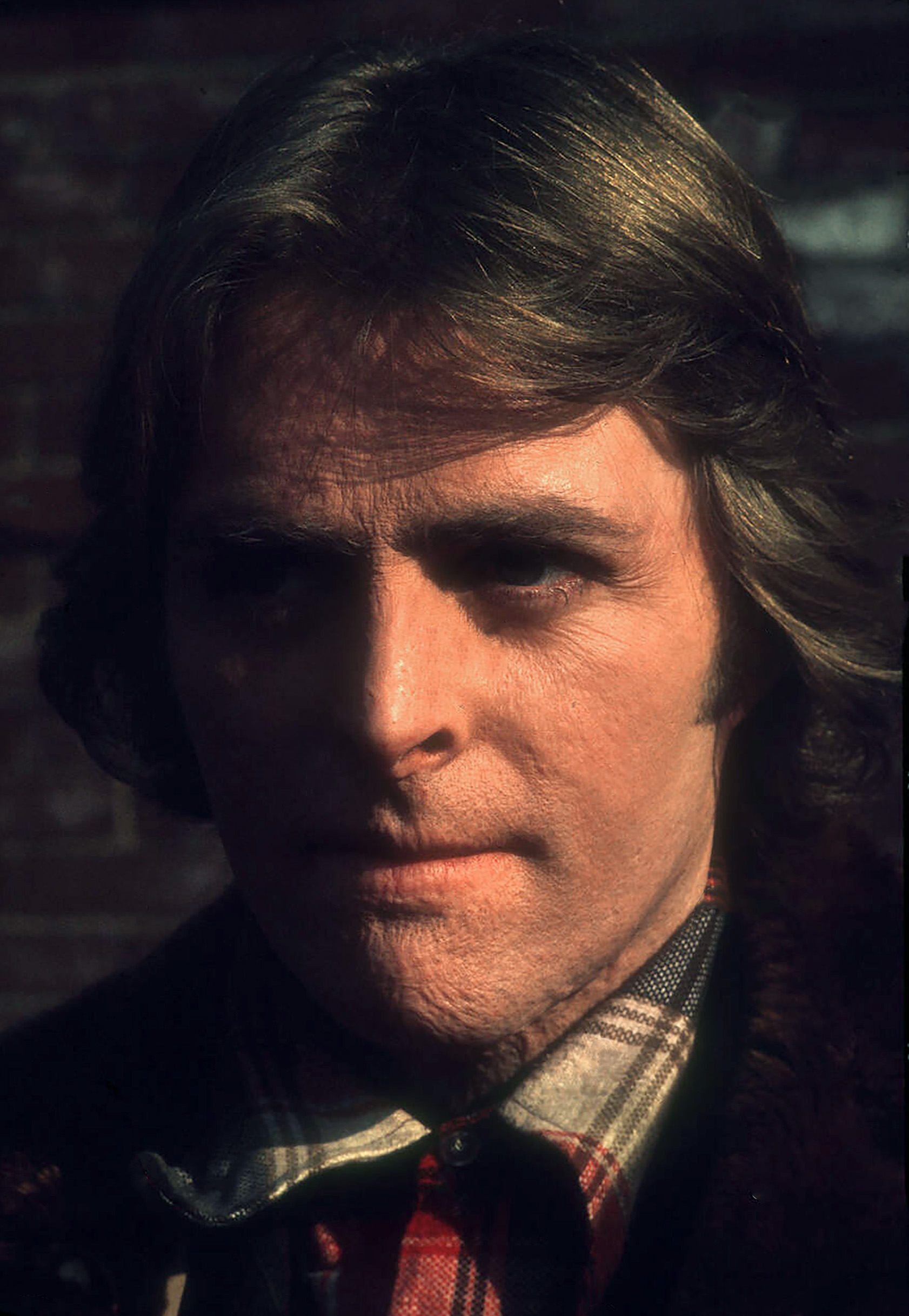

Filled with eccentric character actors, The Seven-Ups stars Roy Scheider as the main protagonist, with a supporting role played by Italian-American actor, Tony Lo Bianco (who just passed away last month). As an added bonus, the movie features an epic car chase with stunt driver Bill Hickman that rivals the ones in D’Antoni’s earlier productions.

While The French Connection spent a good portion of its story in Brooklyn, The Seven-Ups gives the Bronx its fair share of screen time, which got me highly excited. Whenever a movie features New York’s oft-overlooked northern borough, I’m eager to dive in and find all the locations.

Sting Operation

When I discovered The Seven-ups in the early 2000s, it was like discovering a lost movie sequel. While the characters are technically new, they feel like extensions of the ones established in The French Connection, which happens to be one of my favorite flicks from the seventies.

Another connective tissue is the soundtrack by Don Ellis, who composed the same type of brooding score present in the 1971 film. And of course, the New York photography has the same raw, gritty quality as its predecessor, showcasing some obscure locations in and around the city.

That being said, the location of this opening sequence is not so obscure, taking place in Midtown Manhattan. It was easy to identify since one of the shots clearly shows the building’s address on the wall behind Scheider.

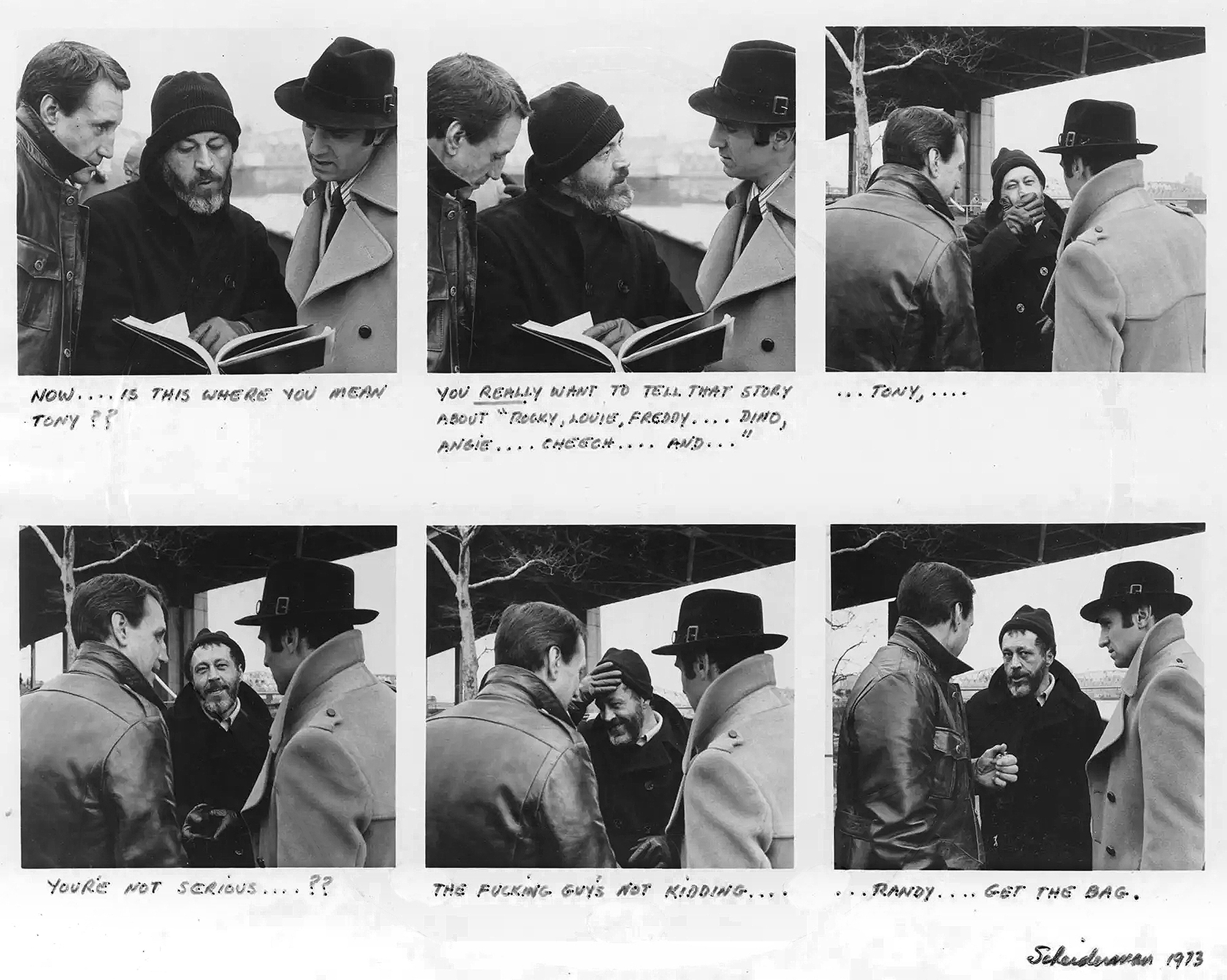

Buddy Meets with Vito

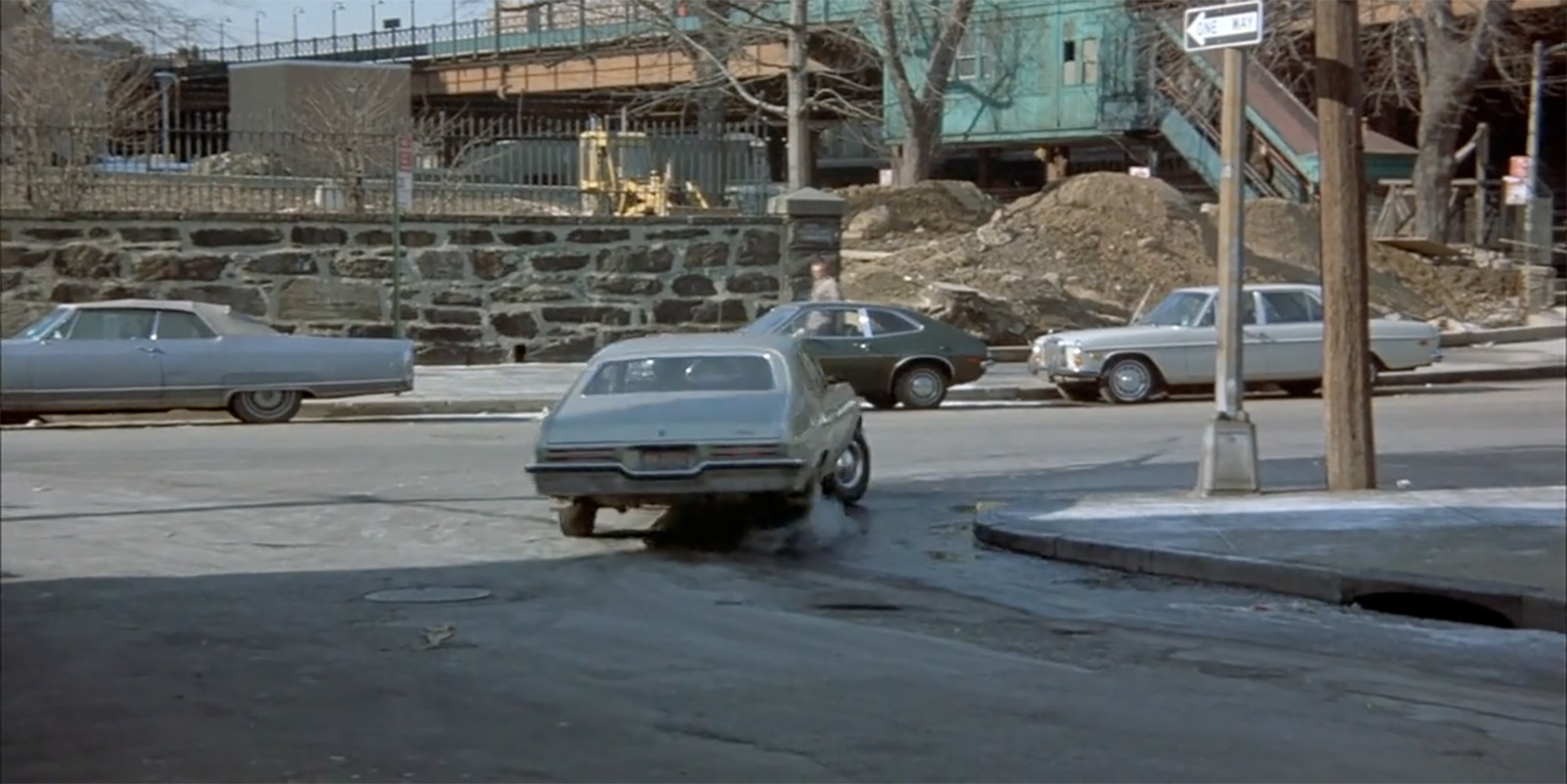

While not completely obvious on its own, this location was pretty easy to pinpoint. The scene was clearly taking place under a bridge with another bridge not too far up the river.

Since I could tell it wasn’t any of the southern bridges on the East River, I started up near the Triborough Bridge (renamed RFK Bridge) in East Harlem. Almost immediately, I became convinced that that was where they shot this scene. The primary clue was the Willis Avenue Bridge which is just to the north of the Triborough, connecting First Avenue to the Bronx.

It did take me a minute or two to confirm it, mainly because the bridge has since been replaced. But after digging up a 2009 photo showing the old bridge, I could tell it was a match.

When I figured out this location back in 2016, that section of the East River Esplanade was still a work-in-progress. And years later, things haven’t seemed to change.

The pathway ends at 125th Street at the Triborough Bridge, and the conditions there were a bit unkept with a couple homeless people setting up camp. I wouldn’t go so far as to call it sketchy, but it’s probably not the greatest place to view the East River.

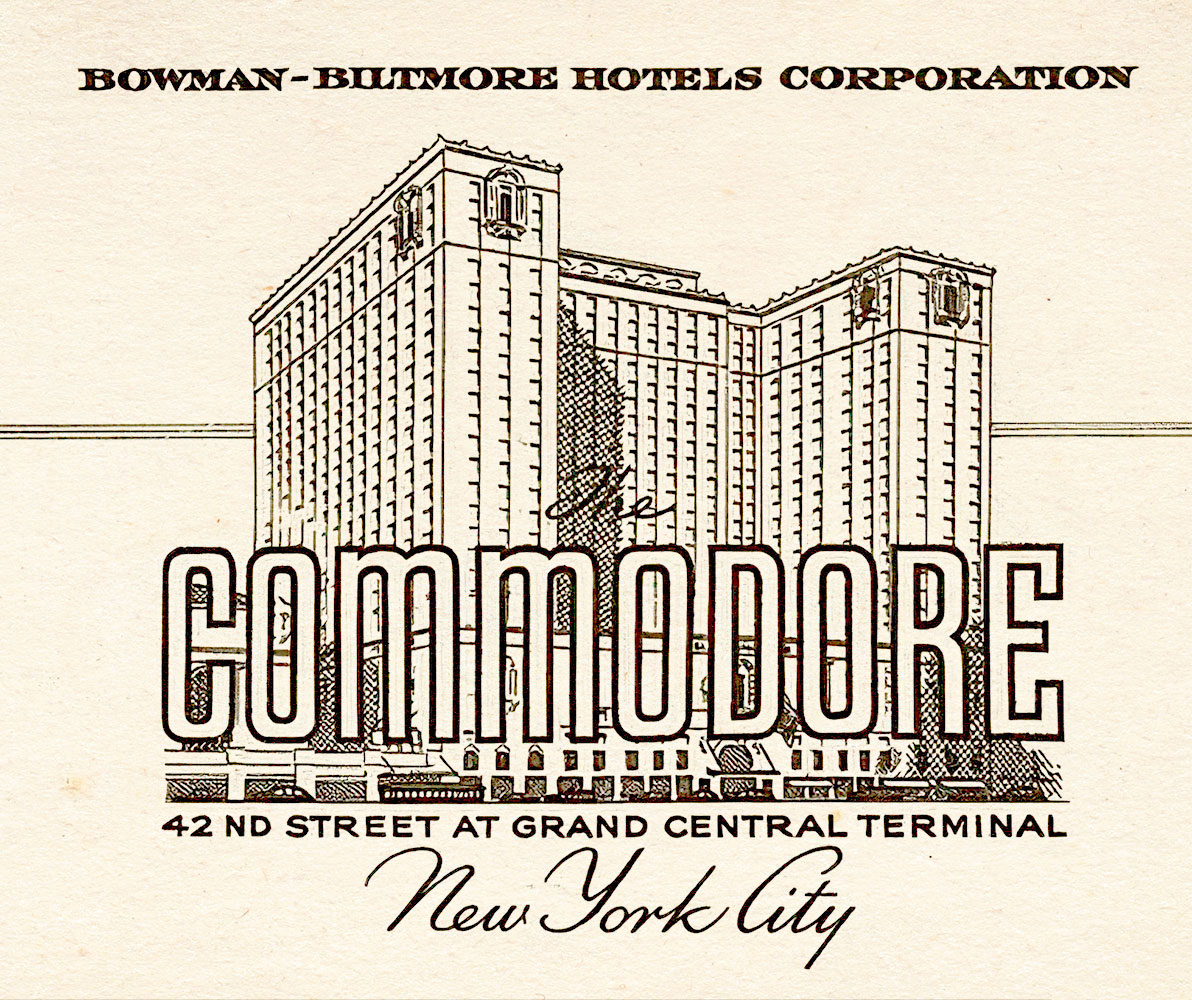

Hotel Meeting

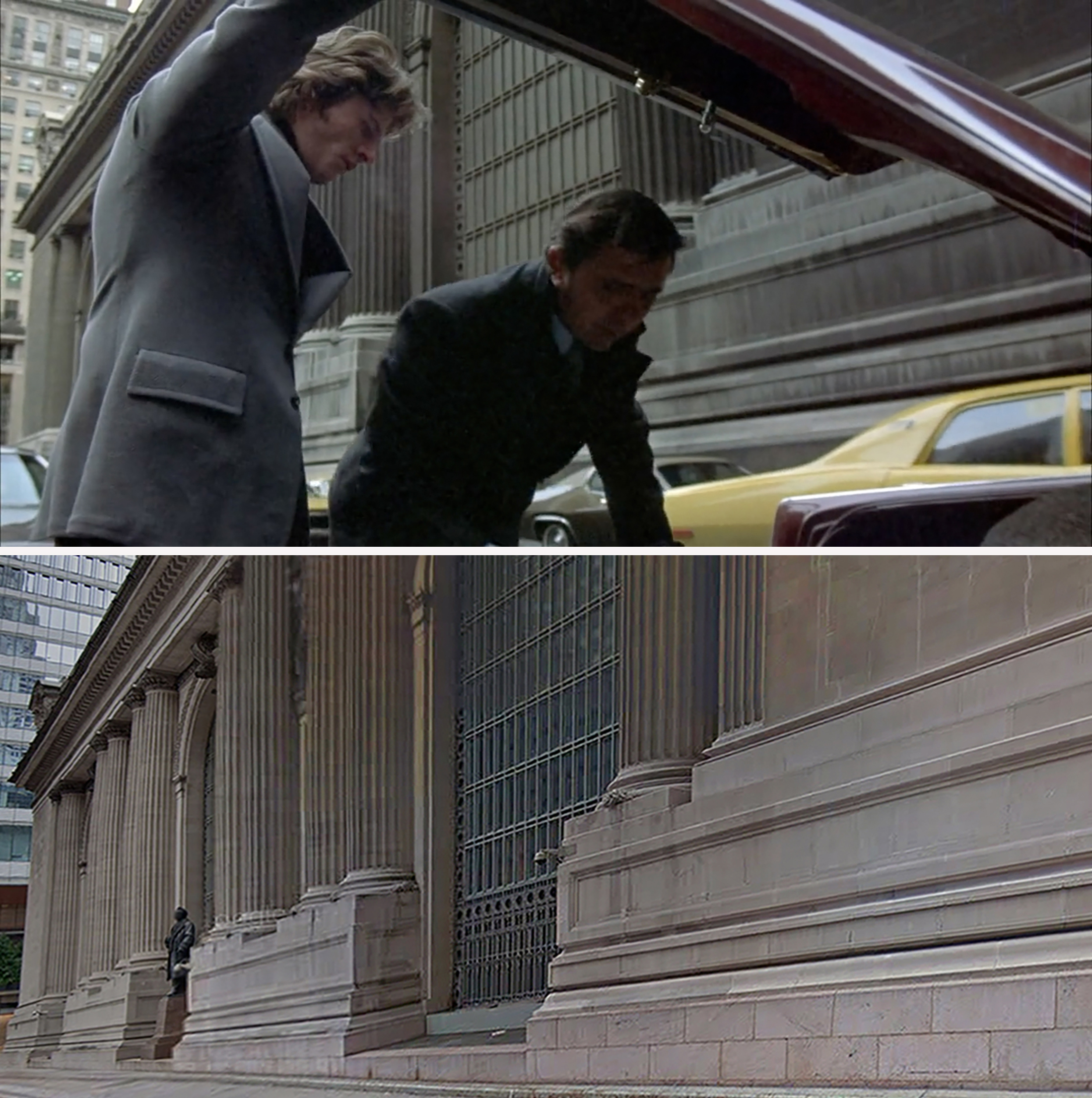

This hotel sequence is significant in a couple ways, the first being the fact that part of it was filmed on the Park Avenue Viaduct.

Until I began investigating this movie, I had no idea the hotel had a second story exit that connected to the viaduct. I always assumed that area was strictly off-limits to pedestrians, but I had no problem going there a few years ago to take these modern pics. It’s pretty amazing since you can get nice and close to the upper level architecture of Grand Central Terminal without having to deal with any large crowds.

The other significance to this sequence is with the hotel itself.

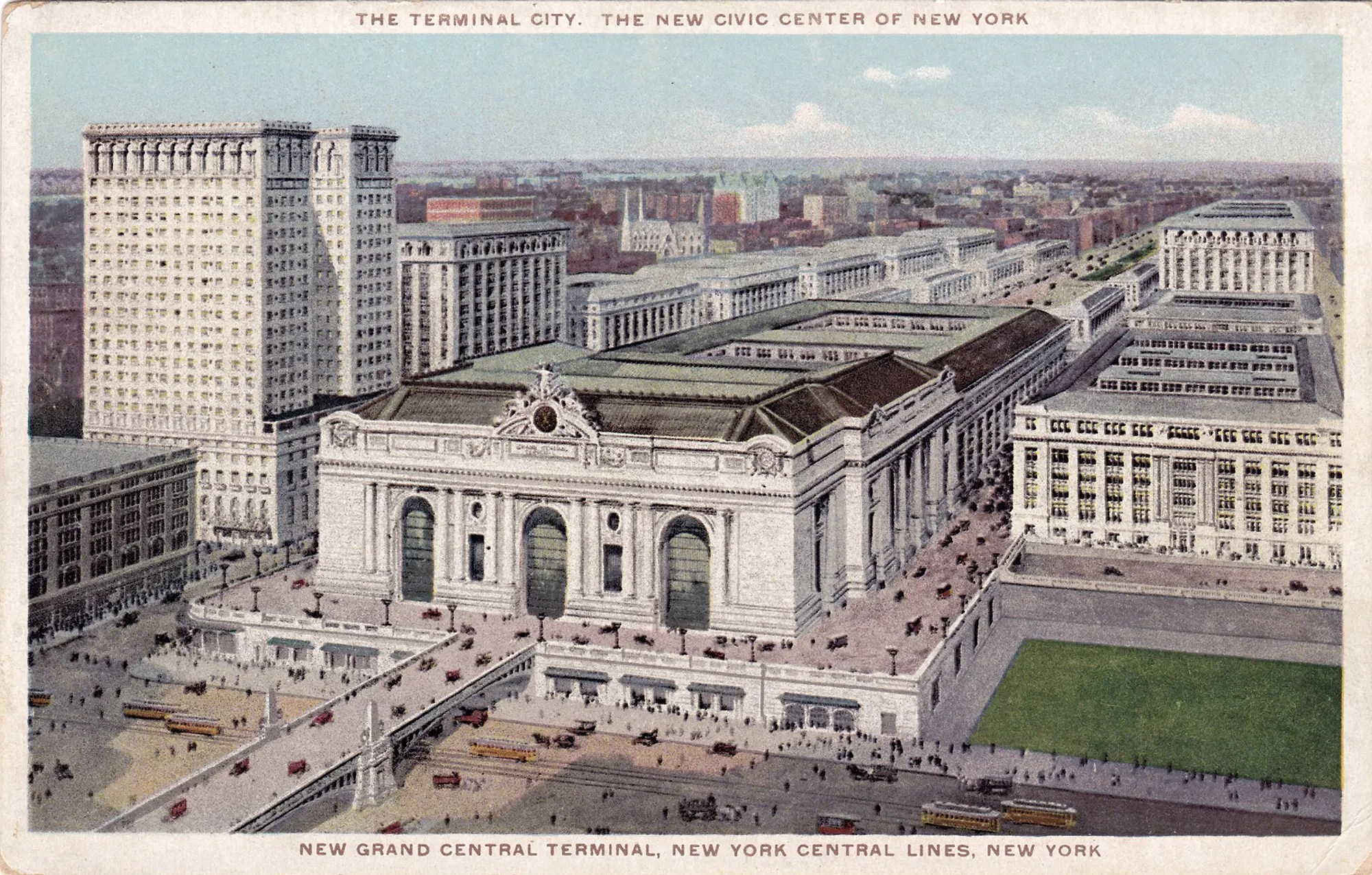

What is now called the Hyatt Grand at 109 East 42nd Street, originally operated as the famed Commodore Hotel when it opened in 1919. Situated next to Grand Central, the 2,000-room Commodore (named for “Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt) was one of the largest hotels in the world, and was considered an important element to New York Central Railroad’s ambitious “Terminal City” project.

This was the second of two railroad-adjacent hotels to open in the same week. The other one was the Hotel Pennsylvania over on Seventh Avenue, which sadly was demolished just a few months ago, despite its landmark status.

On opening night, nearly 3,000 people gathered in the Commodore’s grand ballroom (billed as the single largest room ever constructed) to celebrate the beginning of a new era of luxury accommodations in New York. Lasting between 1919 and 1976, the Commodore Hotel hosted a variety of major events and had its fair share of noteworthy guests, including baseball star Babe Ruth and president Calvin Coolidge.

One of the Commodore’s marketed features was its unique accessibility. This included a direct connection to Grand Central, giving subway/railroad passengers means of entry without ever having to step foot outside.

While the hotel’s main entrance was on 42nd Street, there was also a special motorists’ entrance on the viaduct, as seen in The Seven-Ups. Guests could leave their cars outside this entrance, and as they checked in with the second-level desk, an attendant would park their vehicle at the nearby Commodore-Biltmore Garage.

In addition to its proximity to a large train station, by mid-century, the hotel was near Manhattan’s first airline terminal, located on the southwest corner of Park Avenue and 42nd Street. It was a one-stop aviation facility where passengers could make reservations, get tickets, check their baggages, and then get transported by bus to either Newark or JFK Airport.

In the 1960s, as the city’s fiscal crisis began growing, it took its toll on “Terminal City.” By the 1970s, a rundown Commodore was consistently losing money, and it began earning a bit of a sleazy reputation.

By the time these Seven-Ups scenes were being filmed, it had become obvious that the hotel was being used as a place for lurid rendezvous, complete with in-room X rated movies and a less-than-legit massage parlor in the mezzanine called Relaxation Plus.

The parlor was eventually forced to close in May of 1975 after six private detectives reported that they engaged in “sex acts” with the masseuses for $20-$50. (Sounds like a real tough assignment for the detectives.)

Meanwhile, the Commodore Hotel’s occupancy rate was steadily declining, reaching a point where only half of the rooms were being rented. The owners knew they were irrevocably approaching foreclosure, and on the morning of May 18, 1976, after their last official guest checked out, they permanently closed their doors. But something else was brewing.

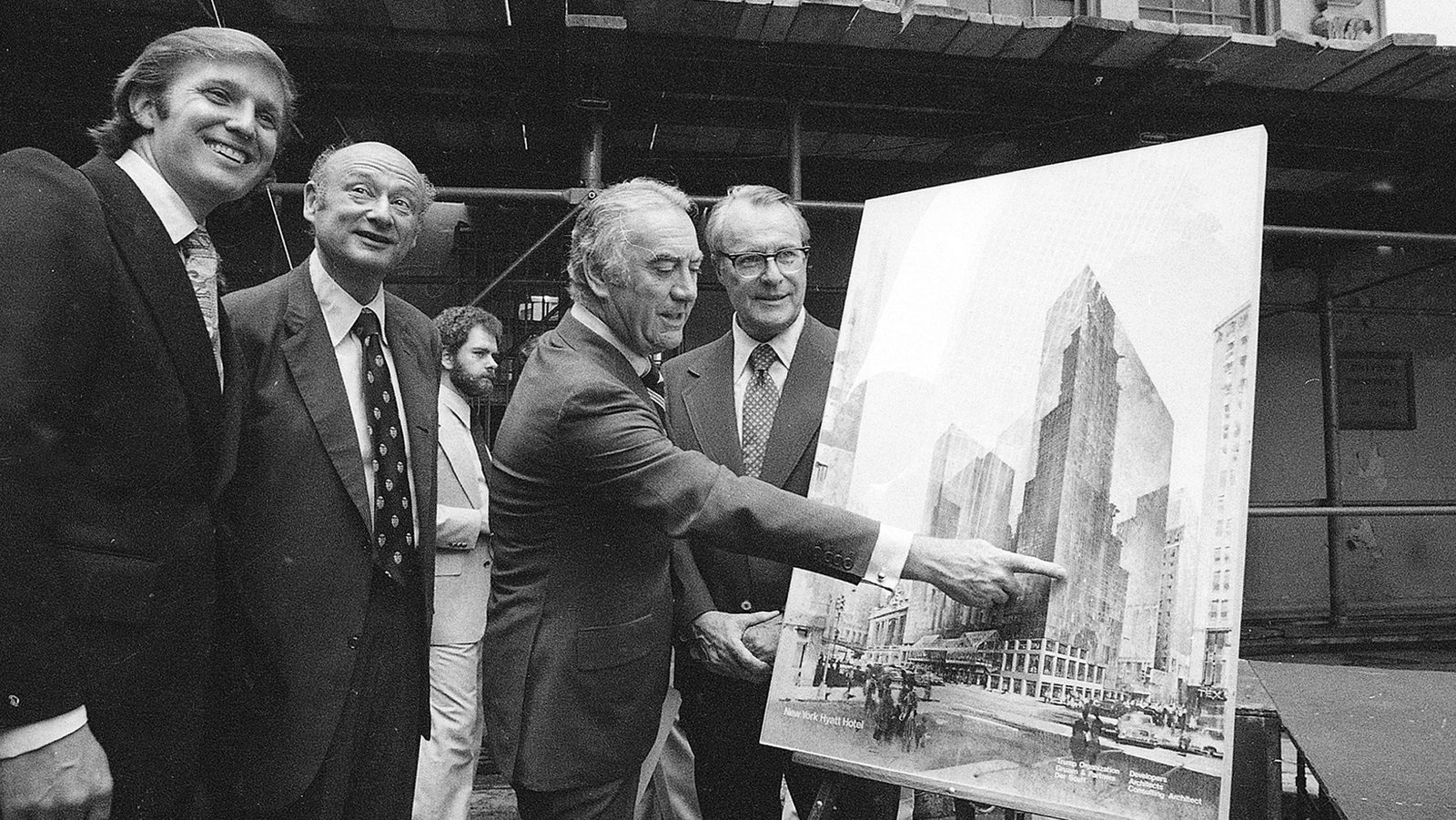

As the Commodore was winding things down, Grand Hyatt and a rising real estate developer named Donald Trump invested in the property with plans of creating a new, modern hotel.

It began when Trump managed to negotiate an unprecedented 40-year tax abatement by the city (amounting to a $1-a-year lease agreement). From there, he oversaw a $100 million renovation to the building. This included removing almost all of the Commodore’s original decorations and shrouding the facade in dark glass, which some architectural critics called, “presumptuous” and “sinister.”

But the new 1,400-room Grand Hyatt turned out to be a huge hit when it opened in 1980, helping put Donald Trump on the real estate map. It also boosted enthusiasm in the modernization of the city and helped revitalize the neighborhood.

In 1996, Trump sold his half of the hotel to the Pritzker family’s Hyatt Corporation for $140 million, bringing an end to what was often described as an acrimonious partnership. To further distance themselves from their former partner, the Pritzkers updated the hotel in 2011, shedding a lot of the Trump “glitter,” including the gold pillars and mirrored ceilings in the casino-style lobby.

The 42nd-Street hotel is still in operation today, but it appears its days are numbered. In 2026. the building is expected to be torn down and replaced with a massive 85-story skyscraper, operating under the title, Project Commodore.

When completed, the glass and metal replacement will become the tallest skyscraper in Midtown East, surpassing other recent office buildings that arose from the 2017 Midtown East Zoning initiative. As described by its developers, Project Commodore is designed to “create more public space” and “make considerable improvements to the surrounding infrastructure.”

At any rate, with an expected opening date of 2030 (which I’m sure will get delayed), we have a bit of a wait before we can see if this redevelopment becomes a hero or a hinderance.

Kidnapping Max

Whenever I encounter a rural scene with affluent-looking homes, I become pessimistic that I’ll be able to identify it. But fortunately, this was shot in New York City proper (opposed to some nearby town), and the scene contained a pair of street signs.

The fact the street signs were colored white-on-blue, I immediately knew we were in the Bronx. In the first of two scenes shot in this neighborhood, I could see one of the street signs said, two hundred and something-sixth. My guess was that the middle number was a four or five. Then, in a later scene, I could see the other sign, which I made out to say, Fieldston.

Using that info, in conjunction with what appeared to be a roundabout, I was able to home in on the intersection of W 246 Street and Fieldston Road in the Fieldston Historic District. Strangely enough (or maybe it’s by design), Google Street View didn’t have any images of this area, but I was still pretty certain I had the right place based on the general layout.

Once I went to the location in person, I was able to determine that the featured house was 4560 Fieldston Road, and the fake cops were parked on the opposite side of the traffic circle.

I only assume the reason this neighborhood has been omitted from Google Street View is because it’s technically made up of private roads.

The Fieldston Historic District is a 140 acre development in the Riverdale section of the Bronx, containing around 250 early 20th-century houses.

The plot of land that makes up the Fieldston neighborhood was first purchased in 1829. Then, in 1909, a good portion of the land was developed as a private park for country homes.

If you travel up and down this hilly, tree-lined community, you’ll come across a variety of architectural styles, including Colonial Revival, Medieval, Tudor, and Mediterranean. There are even a few modernist homes in the mix.

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated the Fieldston neighborhood a historic district in 2006. However, some critics have accused the push to designate it a historic district was contentious, fueled by ulterior motives. Proponents argued that Fieldston’s rich architectural history and unique topography were enough to warrant a landmark status, whereas others saw the efforts as inhibiting and unnecessary.

Regardless, it is certainly a serene, picturesque neighborhood that is antithetical to the average person’s image of the Bronx.

The quick driving shot that follows the scene in Fieldston was found thanks to two prominent movie theaters seen in the background —the RKO and the Valentine— both on East Fordham Road (and incidentally just a few blocks away from my old Bronx apartment).

The Valentine Theatre opened in 1920 and was one of several movie houses in the Fordham area of the Bronx. According to Cinema Treasures, the main theater had 1,252 seats and the “Roof Theatre” on top of the building seated 482. It was remodeled in 1950 and remained in business into the 1980s where it operated as a triplex.

Ransom & Drop-Off

This sequence took place in three different boroughs. The first was obviously back at Grand Central in Manhattan, the second was in Brooklyn (I’ll cover this location later in the post), and the third was in the Bronx.

The main thing that helped me find the Bronx location was the High Bridge Tower, seen across the river atop a small ridge. I became familiar with the slim tower from my research of The Hot Rock, which has a scene that takes place at the base of it.

It’s hard to know if I got the exact spot since the scene is in the middle of an open lot and the area has been built up a bit (although, it’s still quite remote). I technically had to trespass on the property to get the modern photo, as the land is a Metro North railroad yard.

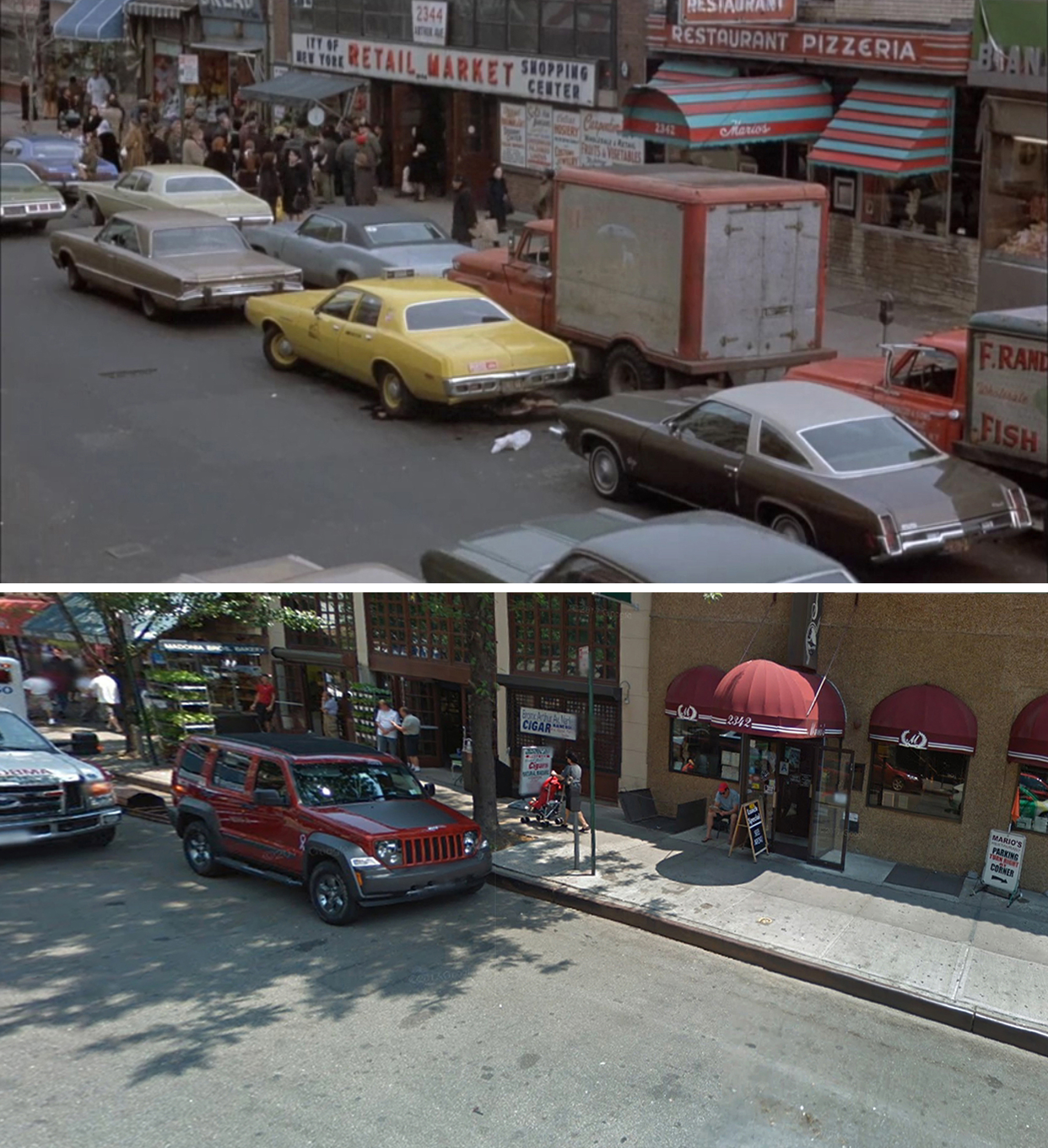

Buddy in Little Italy

I could tell this sequence took place in the Bronx’s Little Italy, I just had to do a little looking around to find the exact spots used. But since this Italian district is fairly small and most of the buildings are still standing, it wasn’t a gigantic task.

When I went to what used to be the barber shop (now an Albanian restaurant named, Teuta Qebaptore), I asked the assistant manager if I could take a couple photos, but was surprised when she appeared a little resistant. In my experience, I’ve found most small, locally-owned businesses are happy to let you take pictures and hopefully get a little publicity.

She eventually allowed me to take a couple quick pics, but I’m not sure why the reluctance. I did read a few reviews on the restaurant that praised the food but said the staff were “unfriendly.” So maybe it’s the Albanian way.

Meeting at the Botanical Garden

When I began investigating this film around 2016, there weren’t a whole lot of location listings on the web, but IMDb did indicate that they shot some footage at the New York Botanical Gardens in the Bronx. And there was only one place in the gardens that resembled the building in the movie and that was the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory.

The beautiful, Italian Renaissance greenhouse was constructed between 1899 and 1902, with renovations taking place periodically over the years.

Like the Hotel Commodore, by the 1970s, the conservatory was in a state of extreme disrepair and it was decided that it either had to be extensively rebuilt or razed. The conservatory was ultimately saved from demolition with a $5 million contribution by publisher and philanthropist Enid Haupt. She then donated an additional $5 million endowment for maintenance of the building.

A subsequent renovation, which occurred in 1978, restored the conservatory to its original design, which had been significantly altered during earlier repairs. It was right around this time that the building was renamed Enid A. Haupt Conservatory in commemoration of her support.

Of all the locations in this film, I’d say this one is the most extraordinary to visit, taking you inside one the most incredible glass structures in the world.

Kidnapping a Bondsman

When I first started researching this movie 5–6 years ago, it took me a little while before I figured out this sequence was shot at Brooklyn’s Borough Hall. It’s funny because I have since become very familiar with the building, mostly from its numerous movie appearances. During the 1970s and 80s, Borough Hall was used often by filmmakers, utilizing its grand rear steps by Columbus Park as well as its courtrooms inside.

Strangely enough, even though IMDb now lists a good chunk of the filming locations from The Seven-Ups, it still hasn’t included Brooklyn Borough Hall. I don’t understand why that is, since it’s certainly less mysterious than some of the other places on the list.

Schoolyard Meeting

The big clue in helping find this location was the pair of apartment towers looming in the distance. Assuming they filmed this scene in the Bronx, I just searched around the borough in Google Map’s satellite view until I stumbled upon the towering Tracey Towers on Mosholu Parkway. From there, I spotted the nearby DeWitt Clinton High School and was able to quickly figure out roughly where this scene took place.

The only tricky part was getting the modern photos on school property since it was surrounded by a chainlink fence which was typically locked up whenever the fields were not being used. A couple times I biked by the school, contemplating climbing the back fence, but never followed through.

Luckily, I happened upon the school one late afternoon and noticed the gate was open, with only a few people on the field. I seized the opportunity and grabbed a few key pics near the bleachers and was on my way.

Funeral

This ended up being an easy location to find since the Lucia Funeral Home is still in business today.

When it comes to local NYC businesses, I have found funeral services tend to stick around. This is because they’re family-run, usually own the property outright, and have a business model that doesn’t dramatically change over the generations. (Let’s face it, us humans keep on dying.)

Aside from the fact the funeral home and surrounding buildings look practically unchanged from over 50 years ago, there are a couple other interesting things about this sequence. One is seeing how big the tree got in front of 2324 Hoffman, the other is seeing the Third Avenue El during its final days in the Bronx.

After the Third Avenue El was completely disassembled in Manhattan in the 1950s, the MTA kept a portion of the line in the Bronx, basically using it as an extended shuttle. Designated the “8 Bullet,” it ran from East 149th Street to Gun Hill Road.

The El finally closed on April 29, 1973 (shortly after production of The Seven-Ups was completed) and all traces of this 19th century relic were wiped away by the end of 1977.

Funeral Procession

There are a couple Bronx parkways that look like the one in the scene — specifically, multiple one-way roadways, separated by grassy, park-like parcels of land. Nevertheless, I was able to figure out that this was on Pelham Parkway mostly thanks to the subway station that appears in the first shot.

It was a little trickier figuring out where exactly Mingo pulled off the procession, since all you really see is grass and a few distant buildings, but I’m pretty sure it was near Bogart Avenue.

One interesting thing I captured while taking pictures of this location was a group of MTA inspectors standing at a “Select Bus Service” stop looking for fare evaders.

On regular buses, riders pay the fare as they get on, but on a Select Service line, riders have to pay their fares ahead of time, using one of the outdoor machines at the stop. After that, it sort of works on the honor system, as no one typically checks for a receipt. The only exception is when inspectors set up a random “stop and check,” as they were doing on Pelham Parkway. If a rider cannot provide a receipt, it can result in a $100 summons.

When this system was first put into place about 15 years ago, I actually got caught on the M15 without a receipt. But luckily, my free transfer was still loaded on my MetroCard, so I wasn’t issued a summons.

The Car Wash

None of these locations leading up to and at the car wash were specifically listed on IMDb when I began researching this movie in 2016. However, the website did list one location to be Mosholu Parkway in the Bronx, which I had a feeling was where the first part was filmed.

Be that as it may, I still needed to do some further research to figure out the specifics. I ended up finding all the stuff on Mosholu Parkway by matching up the buildings in the distance and on the side streets. This was done pretty quickly since the local parkway is only about a mile long.

After going through IMDb’s other generic locations, none of them seemed to be connected to the car wash, so I knew I had to basically start from scratch.

While I was aware the previous scene was shot up in the Bronx, I had a feeling the car wash was down in Brooklyn. Having biked around both boroughs, I knew Brooklyn had a lot more streets with a narrow median strip down the middle like the one in the movie. So, working off that hunch, I began a search for any of the business names that appeared in the scene.

In the end, the thing that got me to Atlantic Avenue was a car wash listing in a 2004 edition of the Kosher Yellow Pages. (I didn’t even know car washes could be “Kosher.”)

Even though the car wash name and facade have changed, and the interior mechanisms have undoubtedly been updated, I had a feeling I found the same place. Naturally, the median strip was an obvious piece of evidence, but after studying the surrounding buildings (which amazingly have stuck around), I found several indisputable matches.

Unfortunately, last time I was on Atlantic Avenue in 2023, I discovered scaffolding had gone up on several of the buildings, which makes me think they’re being prepped for demolition. Although, it is possible they’re just getting some renovations, like the corner building at 1050 Atlantic.

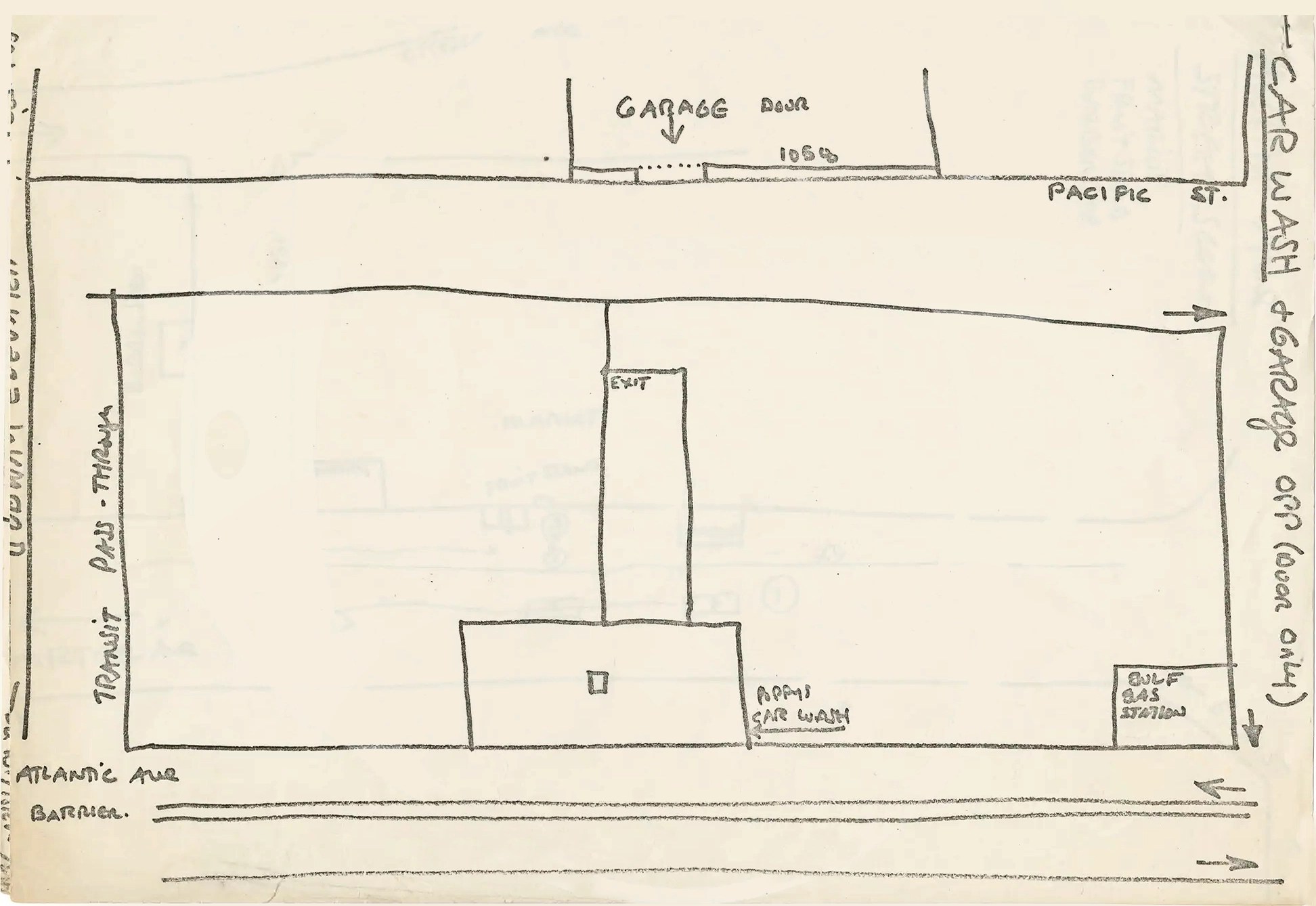

While I was quick to match things up on Atlantic Avenue, I must admit, once the mobster’s vehicle goes through the car wash and Buddy’s vehicle goes through a garage, I got a little lost. At this point in my research, I knew the following garage scene took place in Manhattan, but I had a feeling the garage they go into was still in Brooklyn.

After finally going to the location in person, I got a better sense of the orientation of the scene and was able to match up a few of the buildings on Pacific and finally end my confusion.

Years later, I made a discovery that could’ve saved me a lot of legwork on this location. While looking for behind-the-scenes photos, I came upon a website selling production notes and material from The Seven-Ups, which actually included a hand-drawn map of the car wash location. The map laid out where everything was and confirmed that the garage on Pacific Street was only used for the initial entrance.

Once the car goes inside the garage on Pacific in Brooklyn, the action immediately switches to 56th Street in Manhattan, which will then become the starting point for one of the greatest cars chases in movie history.

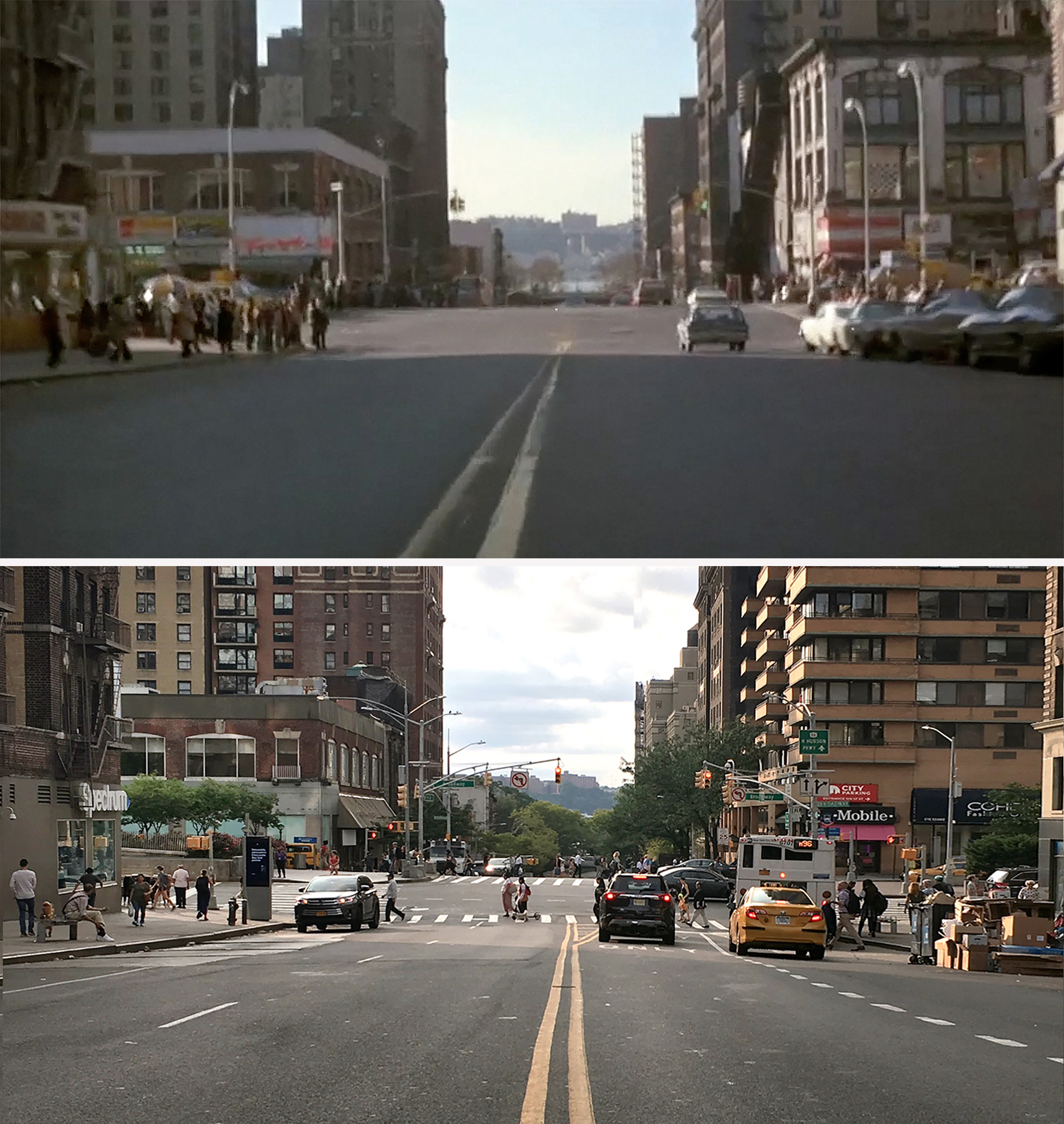

Car Chase – Hell’s Kitchen

Examining this chase sequence as a whole, I could tell the first part was shot in the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood of Manhattan, There were enough clues sprinkled here and there — like the Port Authority bus ramps that appear in the background when they’re on Ninth Avenue, or the Red Cross building that appears when they reach Tenth Avenue (a place I was familiar with from my research on Remo Williams (1985)).

As to the garage location, when the bad guys’ car exits the garage, you can see a sign giving an address of 514-526 W 56th Street.

The garage has since been torn down, but I was able to establish the location by matching up the building across the street. And in doing so, I was also able to establish that all the interiors were shot on 56th Street in Manhattan, opposed to Pacific Street in Brooklyn.

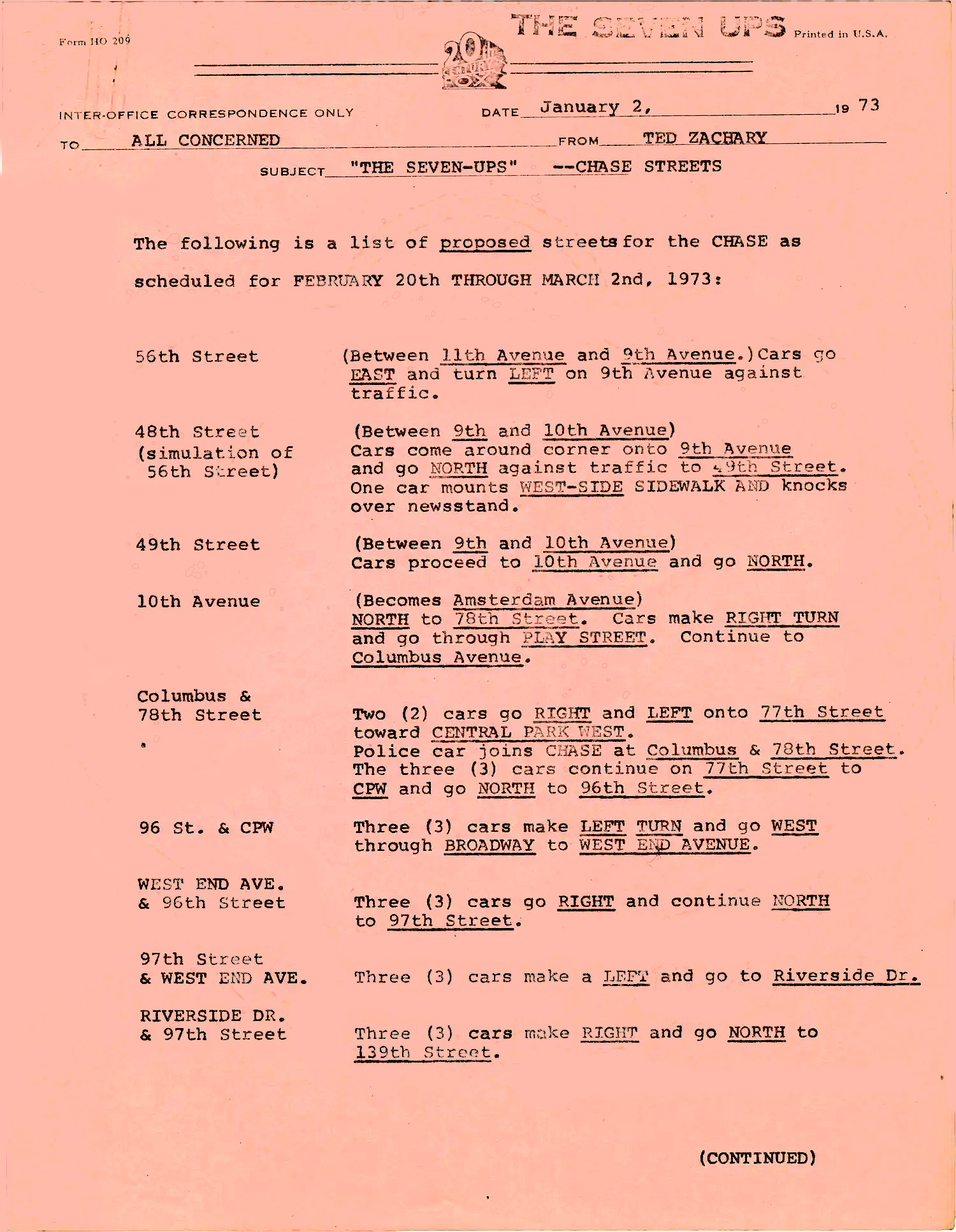

Once I was able to nail the garage location, pretty much everything else in Hell’s Kitchen fell into place pretty quickly. It helped that the geography was a pretty much accurate — the only wonky part was at the beginning of the chase, where they jumped from the garage on W 56th down to W 48th. In fact, you can see a reference to this switch in one of the Seven-Ups production notes I found for sale a few weeks ago.

Dated January 2, 1973, the document was of proposed filming locations scouted out a few months prior to the shooting schedule, but it looked like pretty much all of them were ultimately utilized. In the document, it calls out that W 48th Street was essentially doubling for the street the garage was on.

Once the action switches to Tenth Avenue, things become pretty straightforward. The only geographic glitches come in the form of using the same intersection more than once. This was hidden to most viewers through clever editing and the use of different camera angles. I assume this was done to stretch out the chase a bit and increase the tension.

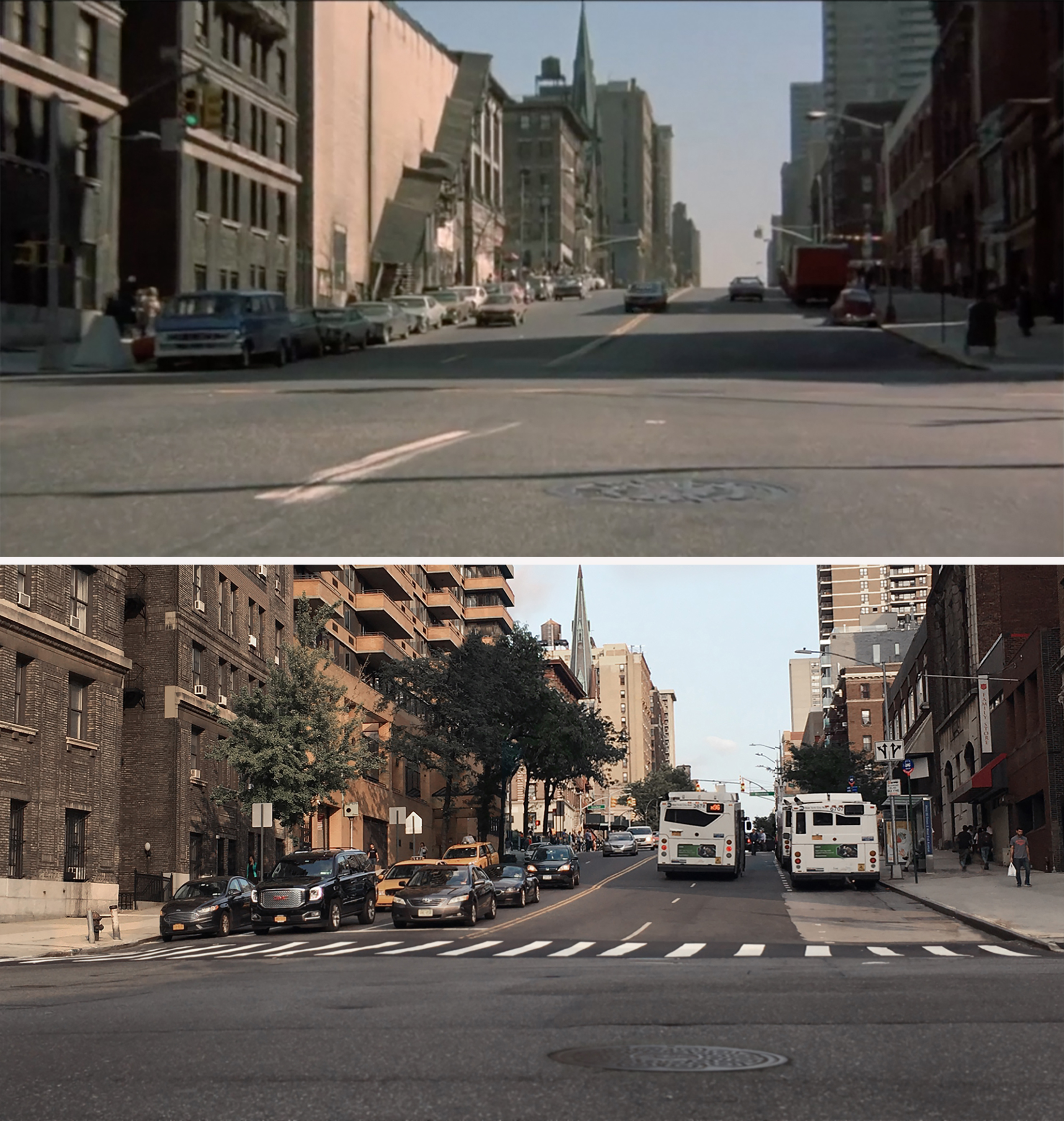

Car Chase – Upper West Side

Once again, since this part of the chase sequence was more or less geographically accurate —minus a few slight jumps and repeats of some intersections— I was able to figure out most of these locations pretty easily. Any time I got stuck, I’d just move ahead to the next location that I could identify and then backtrack from there.

One of the more interesting places used in this part of the chase sequence was W 78th Street where the kids are playing in the street. For some reason, this was a popular block for movies in the seventies. On the corner was the hero building from the Neil Simon comedy, The Goodbye Girl, and about halfway down the block, an alley was used for the 1974 crime-thriller, Death Wish. Not sure why this rather indistinct street was used so many times in a short period, but maybe it had a reputation of being amenable to film crews.

Once the action hits W 96th Street, that’s where the editors do some of the more egregious reusing of the same intersection. By splicing together different angles of the same action, it’s made to look like it’s two different places. They clearly wanted to make it seem like the hill going from Amsterdam to West End Avenue was much longer, which is understandable since the steep slope helped loft the cars into the air at several points.

If you watch this section, you can’t help but be reminded of D’Antoni’s first production with a major car chase, Bullitt. Obviously, the incline on W 96th is not as drastic as the ones in San Francisco, but you can see some unmistakable similarities.

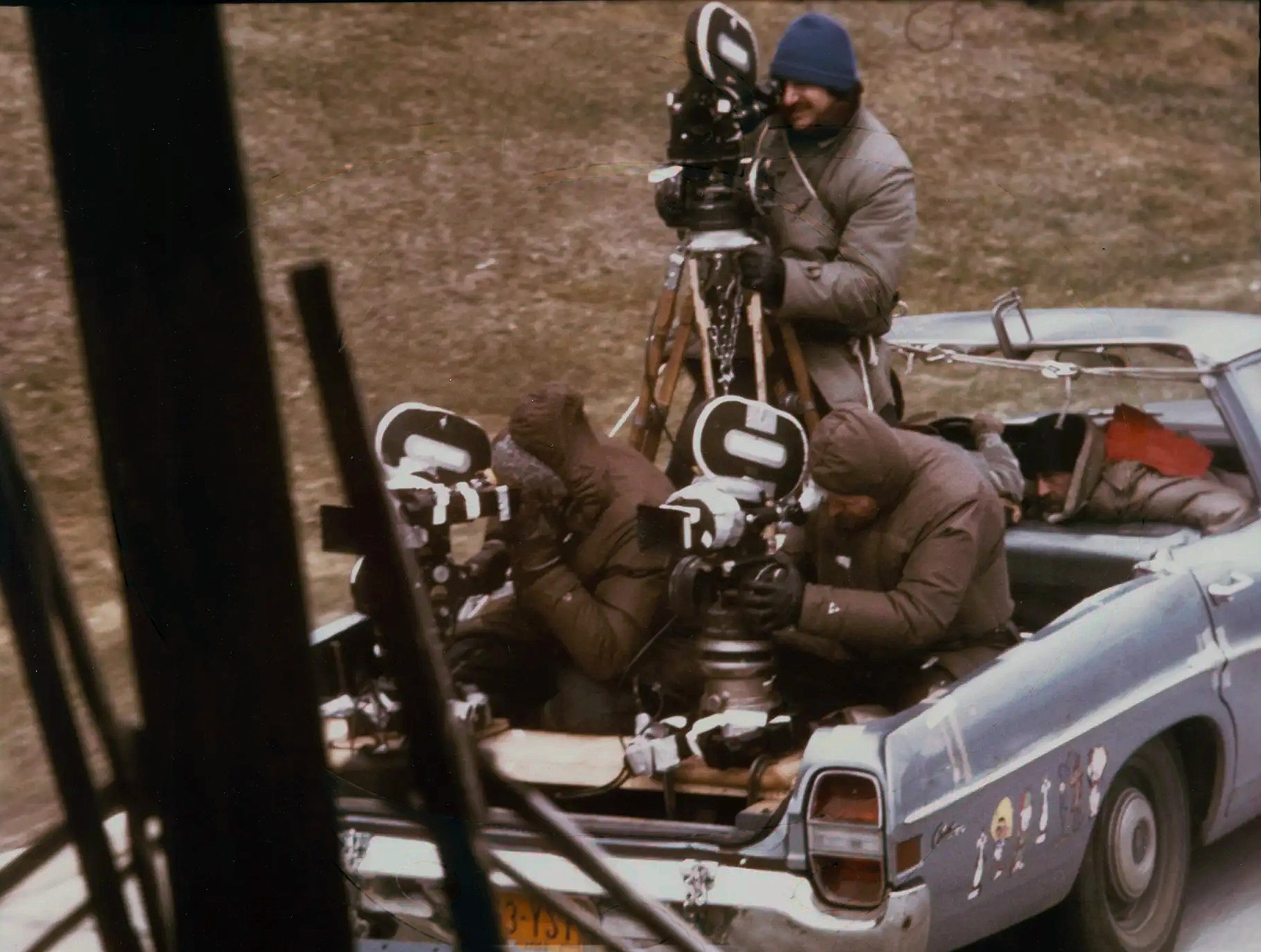

According to production notes, they shot these NYC car chase scenes over a period of about ten working days, and did the stuff in Upstate New York later in the schedule. While most of the driving was done by stuntmen, like Bill Hickman and Jerry Summers, they did have Roy Scheider do some of the driving in a special car rigged with a camera mount.

One little titbit I got from a reader, Frank Farago, about the part of the chase near the Riverside Viaduct. Apparently, if you look along the far rail, you can see a second camera team filming the action from another angle.

It’s one of those things that wouldn’t ever happen in a major production these days, but honestly, I never would’ve noticed it if it wasn’t pointed out to me by the reader (who claims he was one of the people standing there).

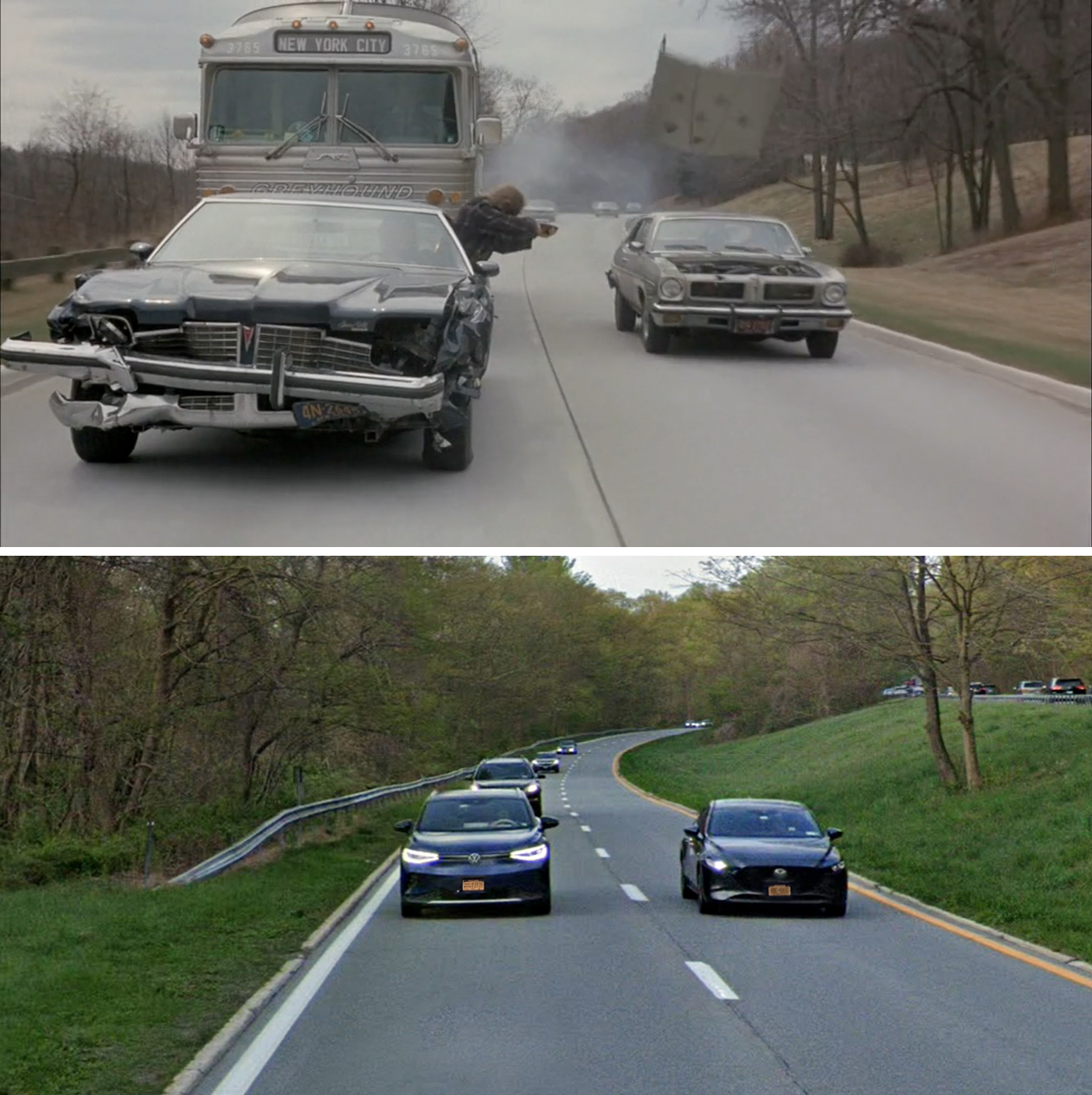

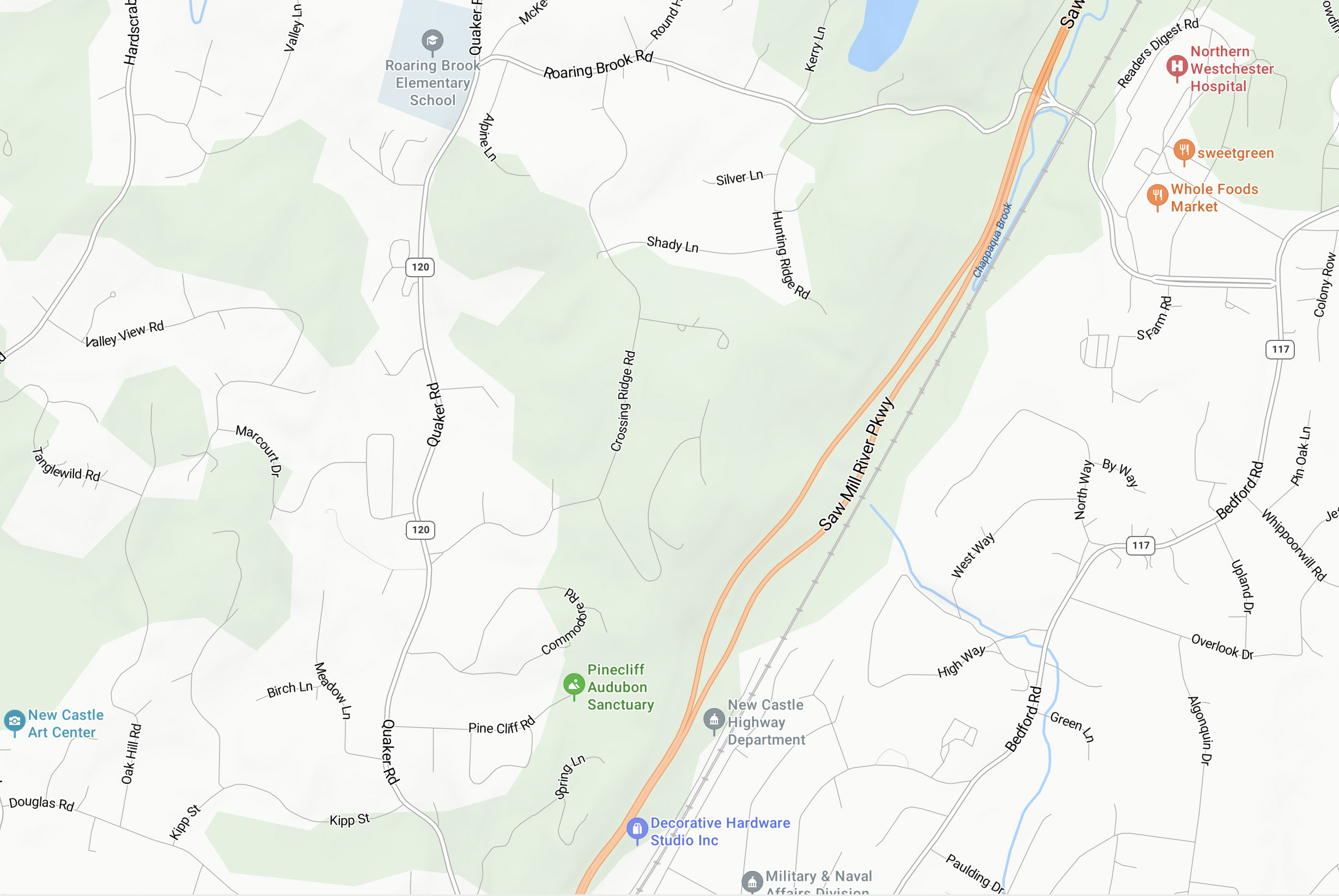

Car Chase – Upstate

Even though the cars go west across the George Washington Bridge into New Jersey, the action almost immediately switches back to the east side of the Hudson River in Upstate New York.

I got a good sense of where the action took place thanks to a discussion on IMDb’s message board (before it was disbanded in February of 2017). The subtopic was the highway locations, but it was mostly geared towards general geographical inconsistencies. The folks discussing the matter were clearly from the Tri-State area, and couldn’t believe the production switched from the New Jersey Palisades to the New York Taconic and Saw Mill Parkways, as if it was a glaring mistake anyone would notice.

No one got into the specific locations, except for the exit ramp where the chase ends. Naturally, since there were a couple signs that appeared at and near the exit ramp, there wasn’t much of a mystery as to where it was taking place.

Finding the location of the previous section with the bus was a little harder, but I eventually figured it out. Given the consensus on the web was that production used both the Taconic and the Saw Mill for this chase, and I knew the ending was shot on the Taconic, I guessed that the earlier stuff was shot on the Saw Mill.

Fortunately, this stuff with the bus was shot at what I assessed to be a unique part of the expressway. You can see there’s actually some large bedrock outcroppings on the median, which normally is just flat grass with maybe some trees. That meant the roadway going in the opposite direction was actually on the other side of those rocks, most likely on higher ground. And if all this was the case, the median was probably quite wide.

So, I just followed along the Saw Mill on a map, looking for any parts where the northbound and southbound sides were separated by a wide median. After checking out a couple different places, I landed on a strip outside of Chappaqua. Once I looked at that strip in Google Street View, I spotted some matching rocks on the northbound side, verifying that I found the right place.

After that, there wasn’t much more to search for. That’s because the entire section of the chase involving the bus was filmed at essential the same spot — they just backtracked and reused that same stretch of road a couple times. This was probably because the crew only had a small portion of the parkway closed off for them.

When it came to taking modern photos of the parkway, since I don’t have a car, I ended up biking there, which ended up being a fun, albeit tiring, excursion upstate. Since the traffic was pretty heavy when I reached the filming locations, it was a little dangerous running onto the parkway and taking pictures, but I made it without getting hit by any cars.

Boatyard

This location was found by matching up the buildings in the Manhattan skyline.

As you can see from the modern photos above, the area has changed dramatically since the 1970s. What used to be a rough waterfront shipyard is now a group of pricy condominiums.

Hospital Interrogation

Even though the name of the hospital is clearly shown when the characters walk inside, I did still have to do a little bit of work to figure out what entrance they used and confirm I had the correct building.

The problem came from the fact that the hospital façade has been heavily remodeled since the 1970s, making almost everything unrecognizable. The biggest help in verifying this location, since I wasn’t able to dig up any vintage photos, was matching up the housing complex that appeared in the background as a car first approached the hospital.

The Gouverneur Hospital at 227 Madison Street was actually quite new at the time they filmed this scene. The original iteration of the hospital was in Manhattan’s Financial District, but it lost its accreditation in 1959 and was forced to close. It was replaced by a new Gouverneur Hospital at 227 Madison Street, which formally opened just a few months before filming began on The Seven-Ups. This new 14-story, 216-bed hospital served Little Italy, Chinatown and the Lower East Side.

Then in 2008, a $180 million modernization project was embarked on the facility, where new and refurbished buildings were added, allowing healthcare services to be expanded by 15%. The project was completed in 2014, making the building 13 stories high, with a new 8-story tower to serve as a nursing home.

White Tower

This is the only location I’m not 100% positive about, but I’m fairly sure that I got it right.

Based on the eatery’s design and decor, I was able to establish that the scene took place at a White Tower — a fast food restaurant chain specializing in hamburgers.

Often considered to be an imitator of the White Castle chain, White Tower managed to stay competitive through a good chunk of the mid-20th century, selling hamburgers at discount prices.

The restaurant’s white decor was supposedly meant to evoke a feeling of hygienic conditions, which was reinforced by having the female staff, nicknamed “Towerettes,” dressed in nurse-like uniforms.

At its peak in the 1950s, there were 230 White Tower locations across America, with several outlets in New York City. But by 1973, the only location I could find in the city was on Broadway in the Bronx.

I haven’t been able to verify that the Broadway White Tower was the only one left in the five boroughs, but the fact that it wasn’t too far from some other filming locations used in The Seven-Ups, I would tend to believe that that is where they filmed this scene.

Also, I recently discovered a fascinating book published by MIT Press about the restaurant chain, aptly titled White Towers, which proved to be helpful in my research. It was chock-full of vintage photos, including one of the interior of the White Tower at 6007 Broadway in the Bronx (designated as New York no. 18). Taken in 1936, the photo showed the basic layout of the restaurant, which strongly resembled what appeared in the movie.

I still wouldn’t call this definitive proof (especially since a lot of the outlets had similar layouts), but it definitely helped support the case. At this point, I would estimate my confidence to be around 95%, but I’m always open to being disproven.

Toredano Released from Jail

When actor Joe Spinell, who played Toredano the garage attendant, exited the jailhouse, you can see both a sign for a “Civil Jail,” and a street number of 434. With that info, I was quickly able to determine that they shot this scene on W 37th Street.

Originally built in 1870 as a police headquarters, NYC’s Civil Jail was a four-story lockup that used to house civil prisoners for all five boroughs. Its inmates included some high-profile labor union leaders who defied court orders to end illegal strikes, infamous racketeers who were in contempt of court, along with your basic, nameless ex-husbands behind in their alimony payments. In fact, for a while, it was widely known as the “Alimony Jail” for all the delinquent men being held there.

After operating for more than 70 years, the civil jail was shut down the year before The Seven-Ups was filmed. My guess is the building got torn down at some point in the 1980s or 90s. I’m actually amazed that there’s still just an empty lot there and it hasn’t been taken over by some giant super-tower.

Final Shootout

This was another location that I found by first getting a generic location on IMDb. On their filming locations page, they listed Erskine Place, with no further information. Fortunately, as the actor, Joe Spinell, goes into his dilapidated house, you can see the number 2083.

Even with an exact address, I still had a little trouble laying out where this sequence took place. The main problem was that, aside from the large apartment tower at 120 Erskine Place, all the buildings that appeared in the movie have since been replaced. The two buildings that intrigued me the most was a large industrial structure that basically formed a dead end on the dirt road, and a rickety nightclub called, Jack’s Red Cheetah — both of which were razed only a few years after this movie was made.

The one structure that semi-survived into the 21st century was the corner house at 2198 Palmer Avenue which didn’t get updated until 2017. So, when I looked at it in an older Google Street View, I could match it up with the scene. Then from there, I could get a good idea of where the rest of the action took place.

Overall, this area of the Bronx was quite interesting-looking back in the 1970s, appearing more like some remote New England town than a part of NYC. Even though the housing has been built up over the decades and the dirt road is now a paved Erskine Place, it’s still quite a remote area.

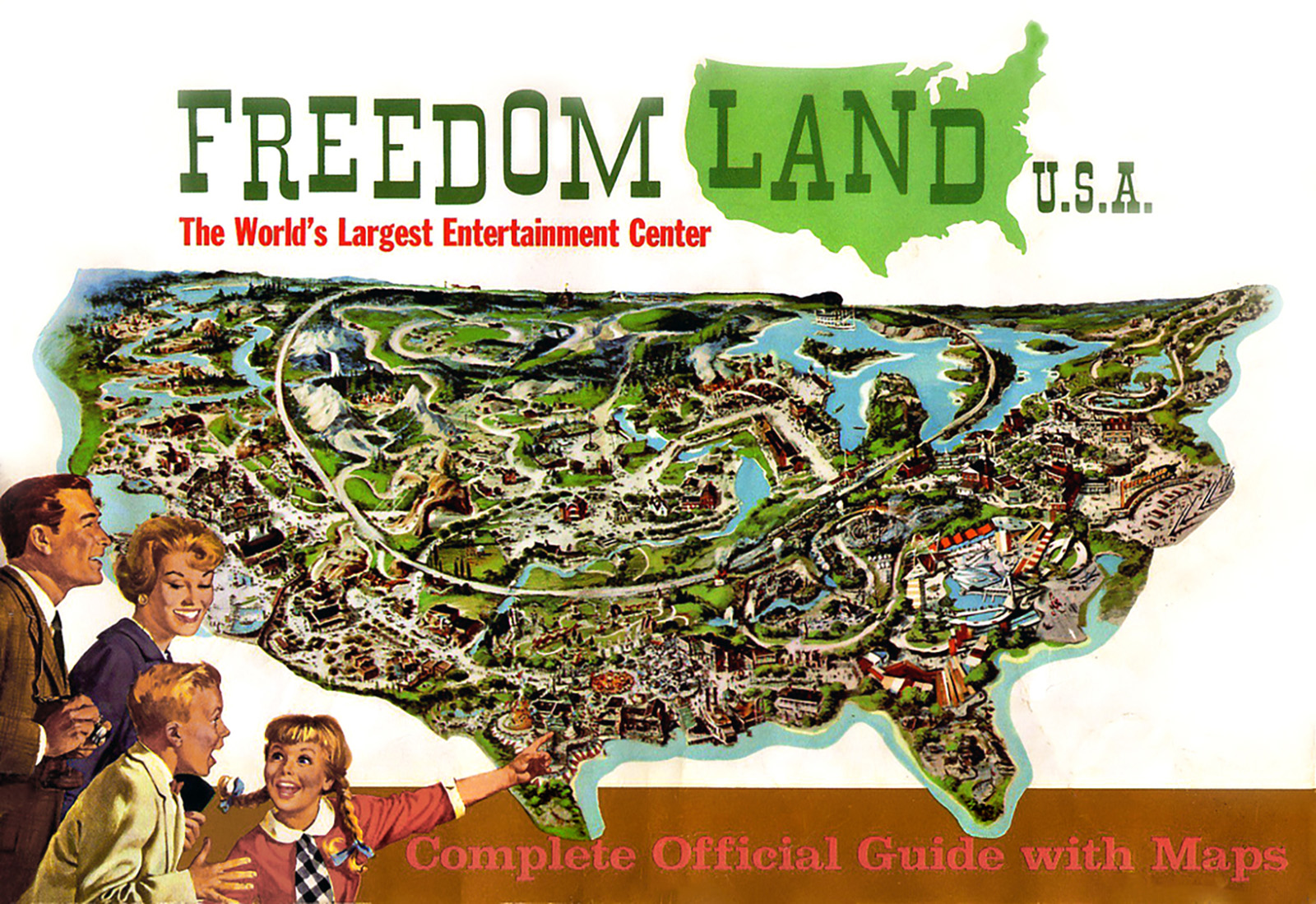

Situated on a marshland along Pelham Bay, the small Baychester neighborhood is home to Co-Op City, one of the largest housing cooperatives in the world. But before the giant housing complex was completed in 1973. a section of the land was the location of an expansive theme park named Freedomland USA.

Filled with rides and attractions dedicated to American history, the 205-acre entertainment center (often referred to as the Disneyland of the East) only operated for a little over four years — from June 19, 1960 until September 1964.

Turns out, Freedomland’s extremely short lifespan may have been planned from the outset. It’s been suggested that Freedomland was a “placeholder” to quickly obtain land variances from the Zoning Board, permitting the development of Co-Op City without the need to undergo a 15- to 20-year monitoring period.

While the neighborhood is now dominated by Co-Op City, the small section where this movie’s climax took place is still made up of modest single-family homes and is quite isolated. It isn’t near any subway stops and doesn’t even have a lot of easy ways to walk there. When I biked there a few years ago to take the modern photos, I had to take this convoluted greenway that took me over a network of highways and railroad tracks that surround the area.

And getting to the rail yard was equally convoluted, but thankfully, it wasn’t completely fenced off. It gave me the opportunity to wander around this isolated, unassuming corner of New York City — a fitting end to my exploration of this 1973 movie.

While not a good as The French Connection, The Seven-Ups is still an enthralling thriller, satisfying almost any fan of the 1971 predecessor. Philip D’Antoni definitely knew how to match the style and mood of his earlier productions, capturing New York’s era of dirty streets and dark corners, but without hammering the idea that menace was lurking behind every corner. We get a sense of some New Yorkers blithely carrying on with their lives, disconnected with the hardened criminals worthy of being sent away for “seven years and up.”

I have a few quibbles with D’Antoni’s direction, but they were mostly technical issues — things I think he would’ve smoothed out if he continued directing. Instead, he chose to transition into television producing, working on several series and TV movies for NBC.

I think he decided to direct this one movie because he wanted to rekindle the magic from The French Connection, giving him the chance to work in his hometown with a lot of the same cast and crew. And it was great that he gave stunt driver Bill Hickman a sizable acting role in this film (which ended up being his last).

I’ve always loved Hickman’s deadpan quality, but by far the most intriguing actor in the bunch is Richard Lynch who played the creepy kidnapper, Moon.

Moon’s ominously scarred look wasn’t make-up, but Lynch’s real-life appearance. It was the result of a 1967 incident where he set himself on fire while on drugs in Central Park, burning more than 70% of his body. After spending a year in recovery, he gave up drugs and began training at The Actors Studio and HB. Because of his damaged appearance, Lynch was often cast as a movie’s antagonist, and in The Seven-Ups, he plays the main nemesis with great delectation.

Of course, the thing that makes The Seven-Ups truly stand out from other 1970s cop movies is its monumental car chase. When comparing it to the chases in D’Antoni’s other productions (French Connection and Bullitt), it’s hard to know how to rate it. On a sheer technical level, I think it’s probably the best out the three. I think Connection had the best concept —a car chasing an elevated train— and Bullitt had the best setting — the winding, hilly streets of San Fransisco.

But to be clear, all of them are spectacular, and worth watching if you haven’t seen them. Each one embraces the integrity of a car chase, without sacrificing any creativity. And the amazing thing is all of them were done without any music — just the sounds of revving engines and smashing glass and metal. Ahh, the simple pleasures of a 20th century action movie.

The aerial view labeled as “Parkchester,” is actually Co-Op City.

And that Erskine Place wasn’t around when the movie was shot. Where the movie was shot was essentially a non-existent, unnamed, street (one of a few in that section of the Bronx at that time). Erskine Place came about a few years later, with the establishment of the last “Section 5” of Co-Op City (’75-’76).

LikeLike

THANK YOU AGAIN!!!!!!!!!!

I will never forget the first time I happened upon the Taconic exit for 133. Of note no trucks or busses were or are permitted on that rout, it was just for the film.

LikeLiked by 1 person

*NOT permitted!

LikeLike

Whew! A lot of research Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

WHEW! !! THANKS

WHAT DETAILS!!

66 YEAR OLD FAN OF THE MOVIE, WHICH I

SAW IN ITS ORIGINAL THEATER RELEASE.

AS A LIFE LONG NEW YORKER BORN IN THE

BRONX AND LIVED IN MANHATTAN I RECOGNIZED

MANY OF THE FILM LOCATIONS AS I WATCHED

THE FILM, I ENJOYED IT SO MUCH THAT I STAYED

IN THE THEATER AND WATCHED IT A SECOND TIME.

THANK YOU FOR TAKING THE TIME IN DOING ALL

THE RESEARCH, IT SEEMS TO ME THAT THIS IS A

LABOR OF LOVE FOR YOU AND I REALLY RESPECT

THAT. IT HELPED RELIVE MANY MEMORIES OF

YOUTH.

THANKS AGAIN

LikeLiked by 1 person

Quite comprehensive. I really appreciate the effort to replicate camera angles through polite trespassing. The site at Madison and 54th that housed the antique shop was replaced in the early 80s with a new office tower. The clothing shop pictured occupies the same space but it is not the same room anymore. Seeing the elevated Franklin Av shuttle tracks over Atlantic Av in one shot clued me in as to where to find the car wash. The White Tower restaurant on Broadway makes sense geographically, just down the hill from the Fieldston location. Feel 100% sure on that one. Some interiors remain mysteries. Gilson’s office, the Seven Ups locker room, Toredano’s lockup and interrogation – some or all of these could be inside the closed Civil Jail. The final confrontation happened on Bassett Av, as Erskine place was still named at the time – the street sign is clear when Moon whips around to draw his gun. I looked up “Chez Rippy” in a 1972 Bronx phone book and found the Boller Av address in Baychester.

LikeLike

Toredano’s lockup and interrogation took place at 43 Herbert Street in Brooklyn NY. A former NYPD precinct now condominiums.

LikeLike

Wil J.

Regarding Toredano’s lockup and interrogation, it took place at 43 Herbert Street a former NYPD precinct. Building is now condominiums.

LikeLike

Director D’Antoni went to DeWitt Clinton High School.

LikeLike

I lived at 1547 Basset Avenue in the 70’s. The train tracks and trains that went by all day may have been the best part. I was just a few blocks away when they were filming the shootout scene – hard to believe over fifty years ago I was probably outside watching trains or playing with a Spaldeen when this was going on a bit down the road. I just discovered this movie last year and I actually like it better than French Connection and like the car chase better than Bullitt. Thank you for doing this outstanding analysis. I certainly did recognize Tracy Towers and Pelham Parkway too!

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing your memories. And yeah, I think Bullitt car chase is a great setting (SF hills), but Seven-ups car chase is better executed. What was the neighborhood like back then? Was it mostly families living there? When I visited the site a few years ago, it still felt quite isolated from the rest of the Bronx.

LikeLike

Thank you Mark! I am 58 now but remember living there like it was yesterday. Yes very isolated. Nothing was on Bassett Avenue and only one or two other families. No kids my age so I learned to be independent and still have fun very early! And I had a blast. Amsterdam Paints was right next door. A welding shop was on the corner of Bassett and Wilkinson. Farberware was across the tracks. There was a Wiseguy bar around the corner called Tik Tok. Mongelli garbage company at the other end of the block. There was a horse stable at the other corner – McDonald Street or Avenue. And the trains. My Dad was a railroad guy. Worked for New Haven and NY Central for a while. Amtrak passenger trains all the time just like the movie. A few freight trains which were the best. Very desolate place to live but I loved it. Will always be home. I could talk Bronx all day. Hit me up if you want to hear more Bronx stuff!

LikeLike