Quite possibly my favorite actor of all time is Gene Hackman (a close second is Hackman’s former NYC roommate, Dusting Hoffman) and when news came earlier this year that he passed away, I knew I needed to do a write-up on The French Connection in his honor.

Considered the break-out movie for Hackman, The French Connection is the epitomic seventies police thriller, full of dark themes, gritty locations, and complex, conflicted characters. Of course, it goes without saying, Hackman’s performance is phenomenal as the stubbornly amoral cop, “Popeye” Doyle, but the real star of this film is New York City. Director William Friedkin paints a cold and indifferent world, showcasing both dilapidated slums and luxurious amenities that co-exist in the Big Apple.

The French Connection was filmed entirely on location, without the benefit of any sets (or sometimes even filming permits), giving us a raw, documentary-like experience. Consequently, all the action feels eerily disquieting, and above all else, completely genuine. This includes what is arguably one of the best and most ingenious car chases in cinema history, executed on the actual open streets of Brooklyn and Queens, often intermingling with real New York traffic and pedestrians.

So, let’s throw on our seatbelts and surge into this seventies classic.

Santa Drug Bust

With pretty much the entire movie shot at real locations, it goes without saying that there will be a lot to cover in this post. And with The French Connection being one of my favorite NYC movies, I might’ve gone a little overboard with all the photos, but hopefully most of them will prove to be insightful and engrossing.

When it came to identifying the locations used in the film, a lot of them had already been figured out by others, most notably by Nick Carr in a 2014 post on his website ScoutingNY. As usual, the site’s author did a dedicated and comprehensive investigation into the filming spots, but considering how much ground needed to be covered, it was inevitable there’d be a few holes in his research.

This included this “Santa Drug Bust” sequence, where he identified most of the places used, but didn’t/couldn’t find a few of the street running locations as well as the empty lot at the end of the sequence.

The streets weren’t too hard to find, despite the fact most of the buildings have been replaced since 1971. I assumed they were somewhere near the bar on Broadway, so I just looked around the area in Google Street View until I found a match. Fortunately, the building at 17 Melrose Street still has the same fake brick facade that was there in 1971 (pretty amazing after 54 years), so it was easy to verify.

Finding the vacant lot where Popeye gives his famous “picking feet in Poughkeepsie” routine wasn’t as straightforward. Carr couldn’t figure it out, and while the message board on ScoutingNY had a bunch of suggestions, I determined all of them to be incorrect. The one thing that was certain was that it wasn’t filmed in the same area as the rest of the sequence. (The reason this part was filmed in a different neighborhood is because it was actually a reshoot of a scene that was originally staged inside a police car.)

The only real clue as to its whereabouts was the set of buildings across from the lot, which had specific door and window patterns. Those buildings would also be the only way I could confirm the location if I found it.

The big problem was, I didn’t really know where to start, as it could have theoretically been shot at a number of different areas of Manhattan, Brooklyn or Queens.

I ended up starting my search in East Harlem, mainly because the rubble-strewn lot reminded me of an alley featured in the James Bond film, Live and Let Die, which was shot in that neighborhood.

But of course, with so much destruction in that area at the time, there was a good chance the buildings across from the lot were long gone. So I decided to use the old tax photos in the NYC Municipal Archives as my main source, going through each East street, one at a time.

Astonishingly, after a couple hours of sifting through old tax pics, I was able to spot one featuring a set of buildings on E 119th Street that turned out to be the ones from the film. It’s often quite easy to miss a matching building in a sea of tax thumbnails, but I got lucky in this venture and it was crystal clear I got a perfect match.

As predicted, those narrow tenements were torn down at some point in the late 80s or early 90s, and both sides of the street received new residential buildings around 2003.

It was very satisfying finally finding this missing location but it’s always unfortunate when virtually nothing survives from a film.

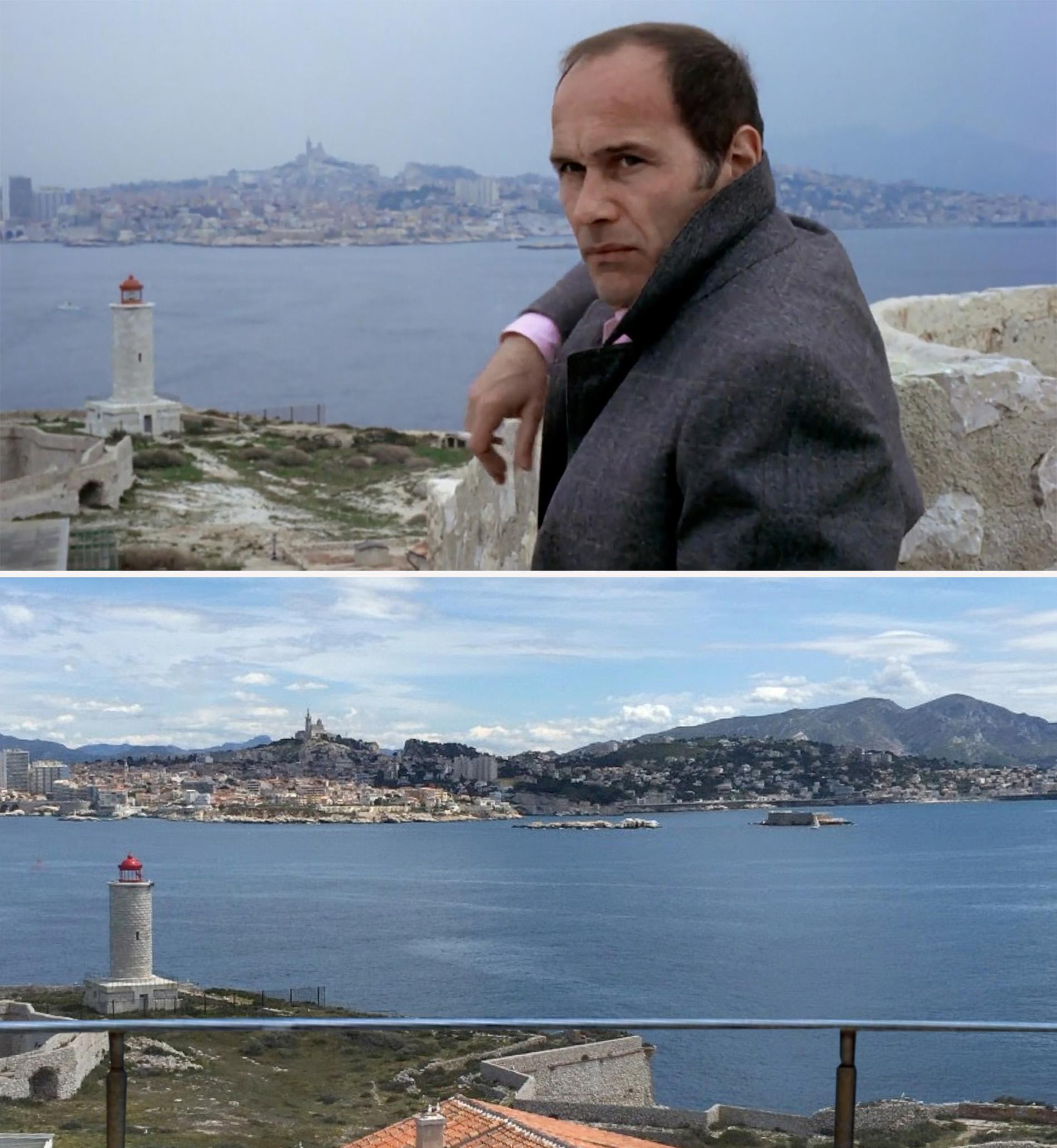

France

As might be expected, most of these Marseille locations were found by other, more continental folks. My main source was a great YouTube video showing the French locales from not only the first movie, but from the 1975 sequel.

I did have to locate two of the locations —the scene on the harbor and the subsequent driving scene — but they were fairly easy to find since they were both on the water in Marseille, limiting the number of places I had to look.

As you can see from the images above, not much has changed in Marseille over the last half century. While most European cities tend to embrace their past and make an effort to preserve its rich history and architecture, New York seems to only make a nominal effort to preserve its landmark buildings, leaving a lot to be destroyed.

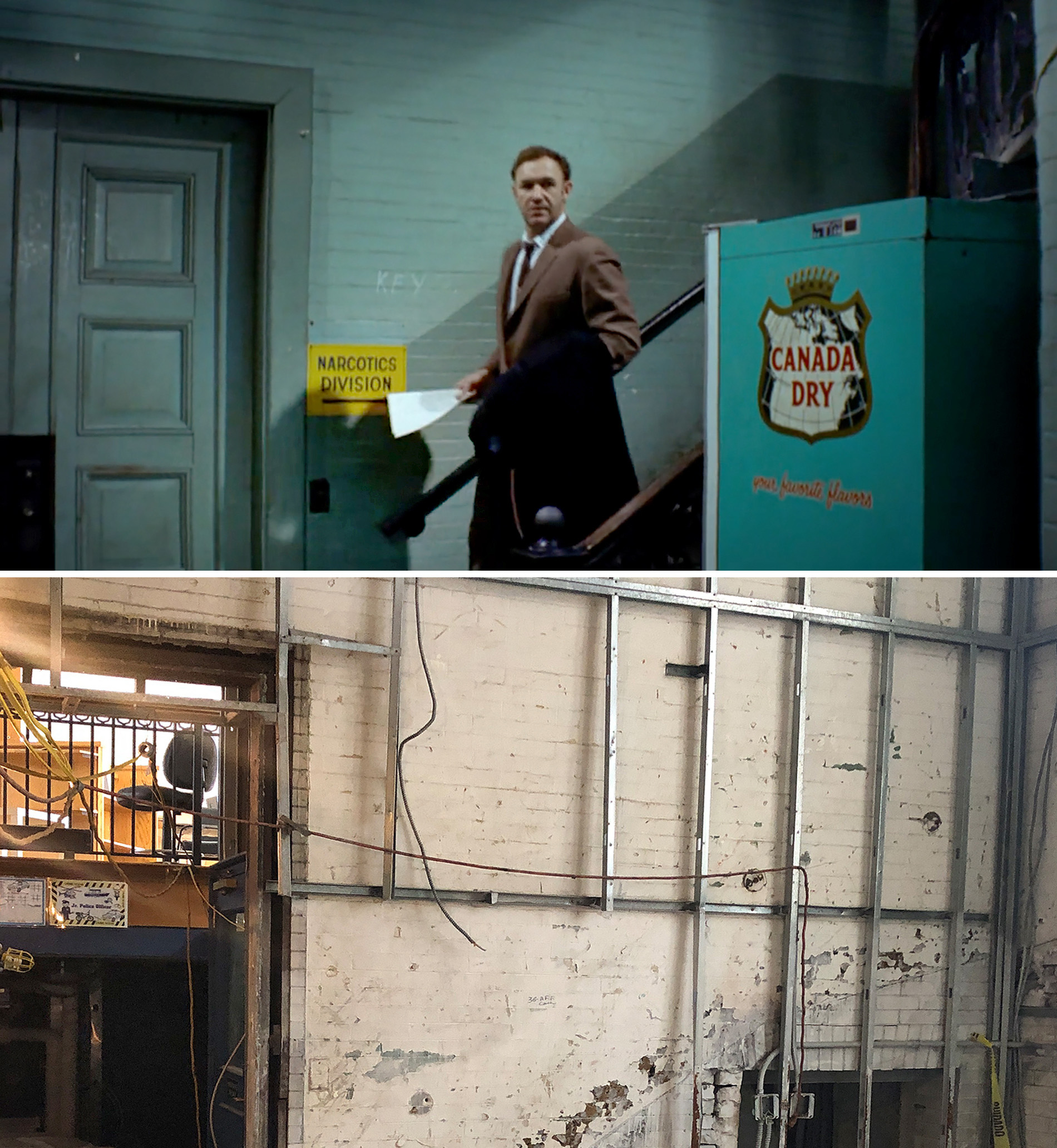

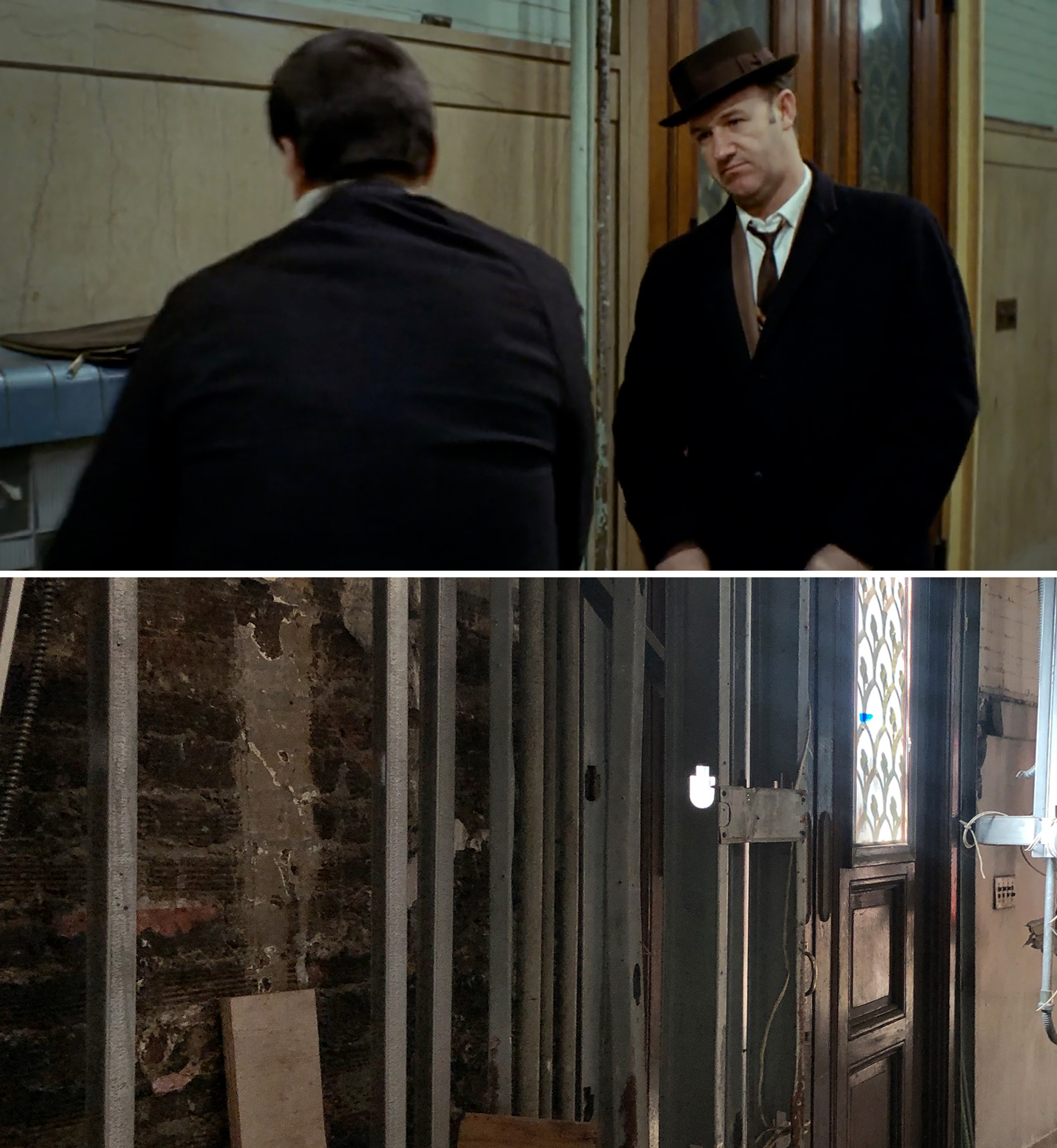

The Station House

Up until about a month ago, this precinct house location was unidentified in all movie books and websites, so I was keen to find it.

In the audio commentary, director Friedkin talked about how they didn’t use sets and how they tried to use the locations of the real-life events that were the basis of the movie’s story. So I figured, since the characters ‘Cloudy’ Russo and ‘Popeye’ Doyle were based on real NYPD detectives Sonny Grosso and Eddie Egan, maybe they used one of their station houses.

Over their years in the force, the two men worked out of a bunch of different precincts, such as the 23rd and the 25th in Harlem and the 81st in Bedstuy, Brooklyn, but none of those seemed to match the movie.

However, with the help of my research partner, Blakeslee, we were eventually able to figure out they shot these station scenes at the original 1st Precinct in Lower Manhattan.

As far as I can tell, neither detective worked out of the 1st Precinct house during their careers; it was probably used by the crew because it was no longer a fully operational station in 1971. What eventually led us to that location was an excerpt from an interview Friedkin did with the DGA (Directors Guild of America) where he casually mentions, “we shot it in an actual police station, the old 1st Precinct in downtown Manhattan.”

Because 100 Old Slip is officially closed these days, I originally had to confirm things by matching up the ironworks on the front door, and comparing the front desk with a scene from Superman: The Movie (1978) which had used the 1st precinct in one scene.

The building hasn’t always been closed. Back in 2002, 100 Old Slip was the official home to the New York Police Museum, but that only lasted about ten years. Due to its location in a highly susceptible area of the flood zone, the 5-story, freestanding building was heavily damaged by Hurricane Sandy in 2012, forcing the museum to move to a temporary pop-up space on Governors Island.

Recently, the city commissioned an architecture and design firm to preserve, rehabilitate and “floodproof” the 115-year-old Florentine Renaissance palazzo, with hopes of reopening it as a museum again.

However, thirteen years after Hurricane Sandy swept through NYC, the structure is still being worked on. While the exterior got a much needed cleaning and restoration, the interior is still gutted and has evidently seen very little progress.

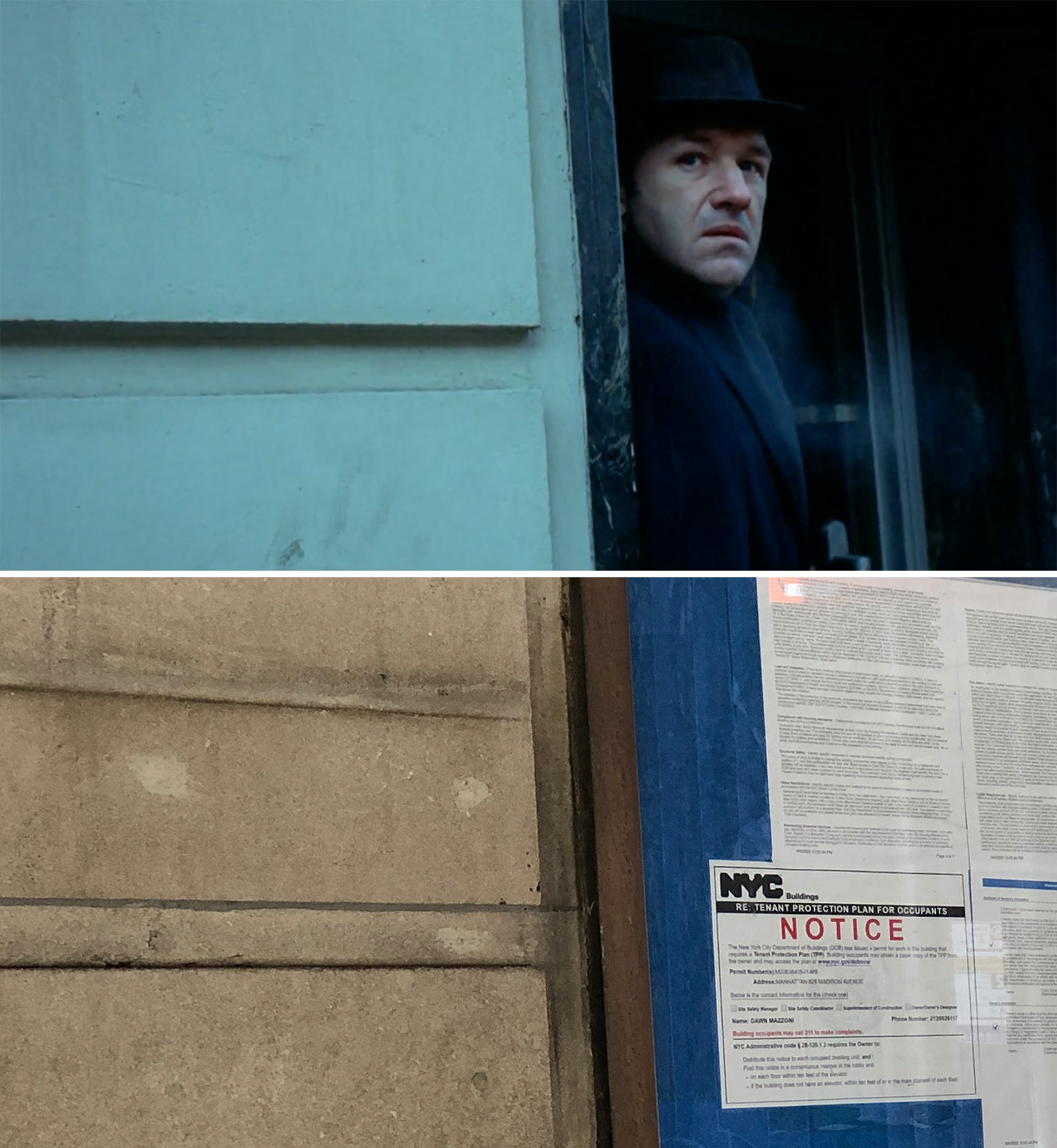

With the building formally closed and under construction, I figured the best I’d be able to do —in terms of modern photos— was grab a couple shots through the windows. But one thing I’ve learned over the years of doing this “NYC in Film” project: even if a building appears locked-up, it never hurts to try opening a door. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve gained access to seemingly closed-off spaces by just stumbling upon an unlocked door and giving it a yank. And that’s exactly what happened at 100 Old Slip.

Knowing there was a back entrance to the building, on a whim, I decided to try it out.

I went to the imposing double doors, waited until the coast was clear, then cautiously pulled at the handle. A few seconds later, to my surprise, the wooden doors slowly started to give way, but I assumed it was because they were chained shut on the inside and just had a little bit of slack. But amazingly, the doors continued to part with no impediments, and before I knew it, I was facing a clear entryway into the aged building.

It didn’t appear as though anyone else was there, so I decided to leap at the opportunity and go inside. My heart racing, I quickly scanned the area, made a beeline to the main entrance where this scene took place, and furiously took as many pictures as possible.

Because the backdoor was unlocked, it technically wasn’t a B&E, but since it could be considered a case of trespassing, I didn’t want to dawdle. So, after about five or six minutes, I curtailed my picture-taking spree and departed from the old police house

Once outside and safely across the street, I was still full of vim and vigor. The first thing I did was send Blakeslee one of the pics I took inside to share the moment with him.

Definitely one of my more thrilling adventures… and another adventure associated with this movie is yet to come.

Nightclub

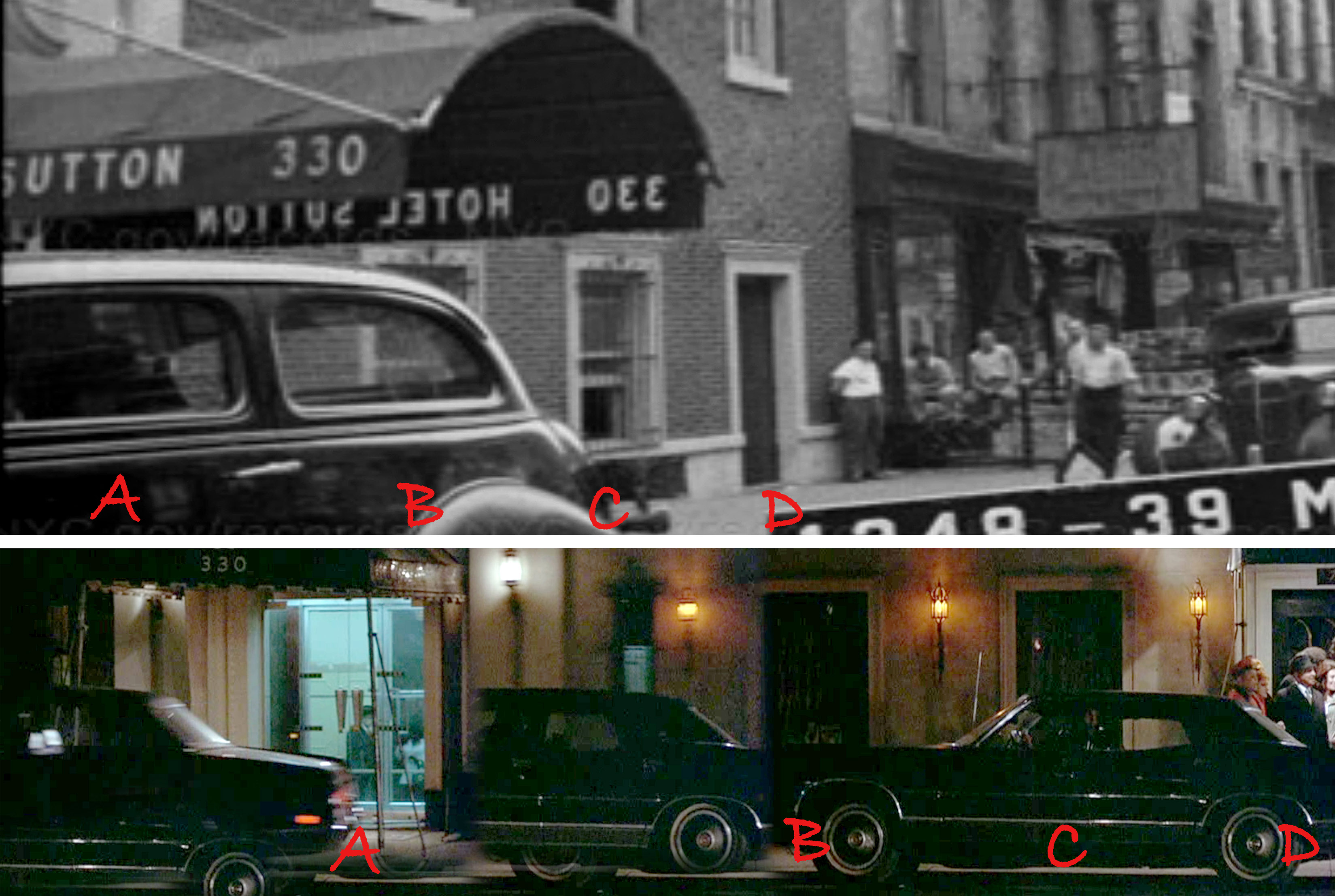

This was a location that was unidentified when I began researching this film back in 2017. There weren’t many clues to go on, other than the number 330 on an awning outside the club.

In the movie, the scene was supposed to be taking place at the famed Copacabana nightclub on E 60th. Being somewhat familiar with the Copa, I could tell they weren’t at the actual place, but it did look like a real nightclub, so I did an internet search for New York clubs in the 1970s to see if any of them had a street address of 330.

It was a slow process, but I eventually came across a 1977 ad for a Pembles discotheque-restaurant that was at 330 E 56th Street.

Only problem was, the building that’s there today looked nothing like what appeared in the movie. So, it was off to the tax records to see what things looked like in the 1940s.

It was a little hard to see, but I did find similarities when I compared the tax photo of 330 E 56th to a composition I made from the movie. The most striking correlation was both of them had a main entrance with an awning, followed by two windows and another entrance.

Even if it wasn’t definitive proof, it was very convincing, and inspired me to dig a little deeper into this Pembles establishment.

First thing I found was a 1970 review in The New York Times that was mostly focused on the club’s supper menu (which included a sirloin steak dinner for $5.95!). However, the thing that offered solid proof that Pembles was the club in the movie was a January 30, 1971 issue of Record World.

The trade magazine had a small blurb about the female singing group, The Three Degrees, announcing that they were chosen by producer Philip D’Antoni to appear in his upcoming movie, The French Connection. But most importantly, the short article confirmed that they would be “seen singing at the Pembles Club on East 56th Street.”

These days, the building is the location of AKA Sutton Place, a luxury, extended-stay hotel that provides furnished apartments with full-service accommodations. The street-level area that used to be Pembles discotheque is now a bar and lounge.

Following Sal in Manhattan

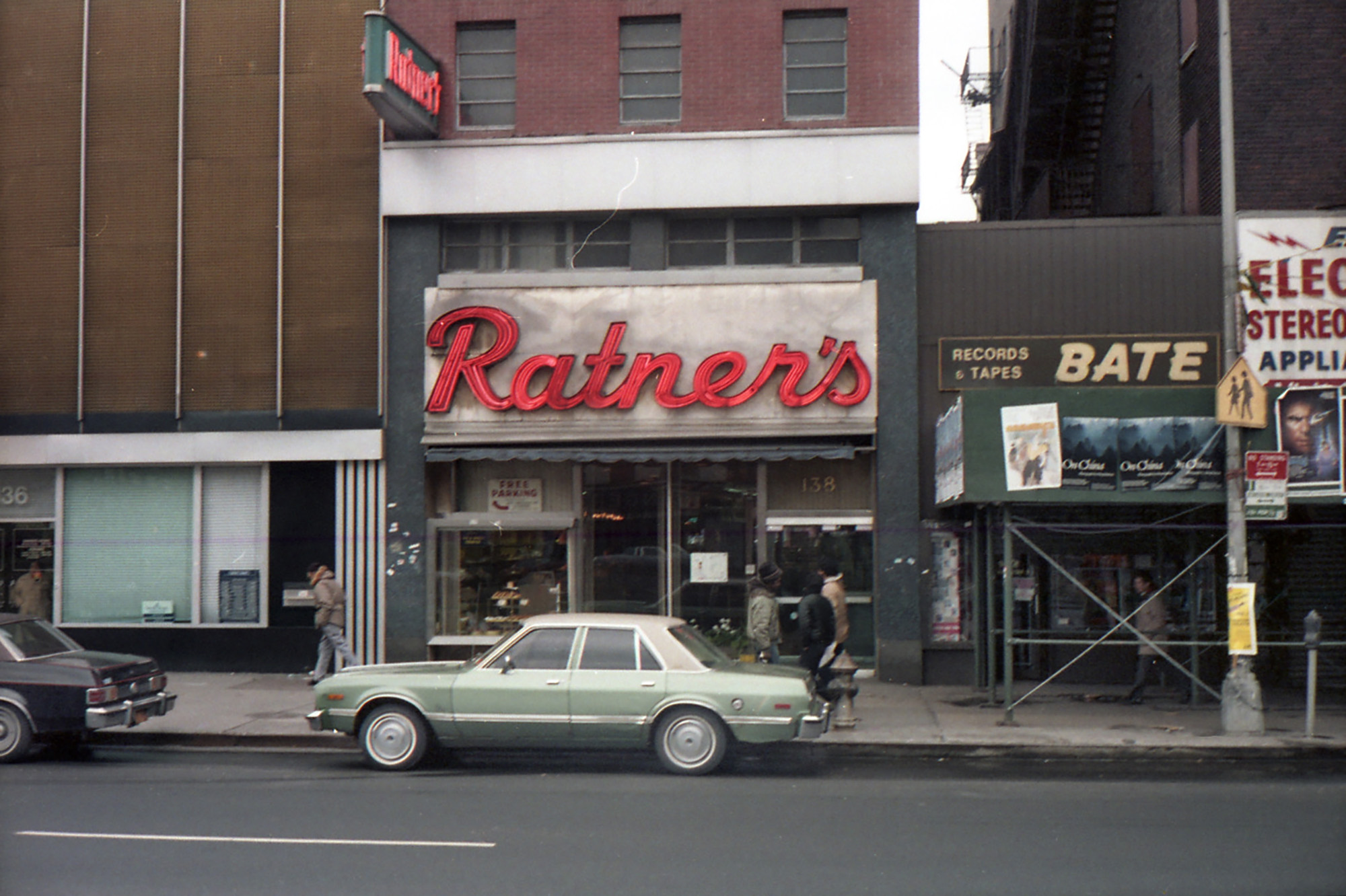

All these locations were already identified before I began working on this film, most of which were published on the ScoutingNY website. But decades earlier, a young French Connection fan had already tracked down several of these locations and photographed them in 1985-86.

His picture of the Williamsburg Bridge was interesting, as it showed the old pedestrian promenade still in place, about five years before it was remodeled in the 1990s.

This young photographer, who’s only known by his Flickr handle, Dr. Speet, also took a picture of Ratner’s, where Sal and Angie Boca are seen exiting during this sequence.

Founded in 1905, Ratner’s was probably the most famous kosher Jewish dairy restaurant on the Lower East Side. These types of dairy restaurants used to be popular destinations in NYC as a solution to the strict rules of separating meat from milk-based products in Jewish law. Basically, these dairy restaurants were an alternative to traditional Jewish delicatessens that typically served meat.

As the 20th century came to a close, this category of kosher restaurant became less common, and in 2002, Ratner’s closed its doors on Delancey Street. However, a number of in-store products are still manufactured under the Ratner’s name, including blintzes, crepes, potato pancakes, pierogies, and matzo balls.

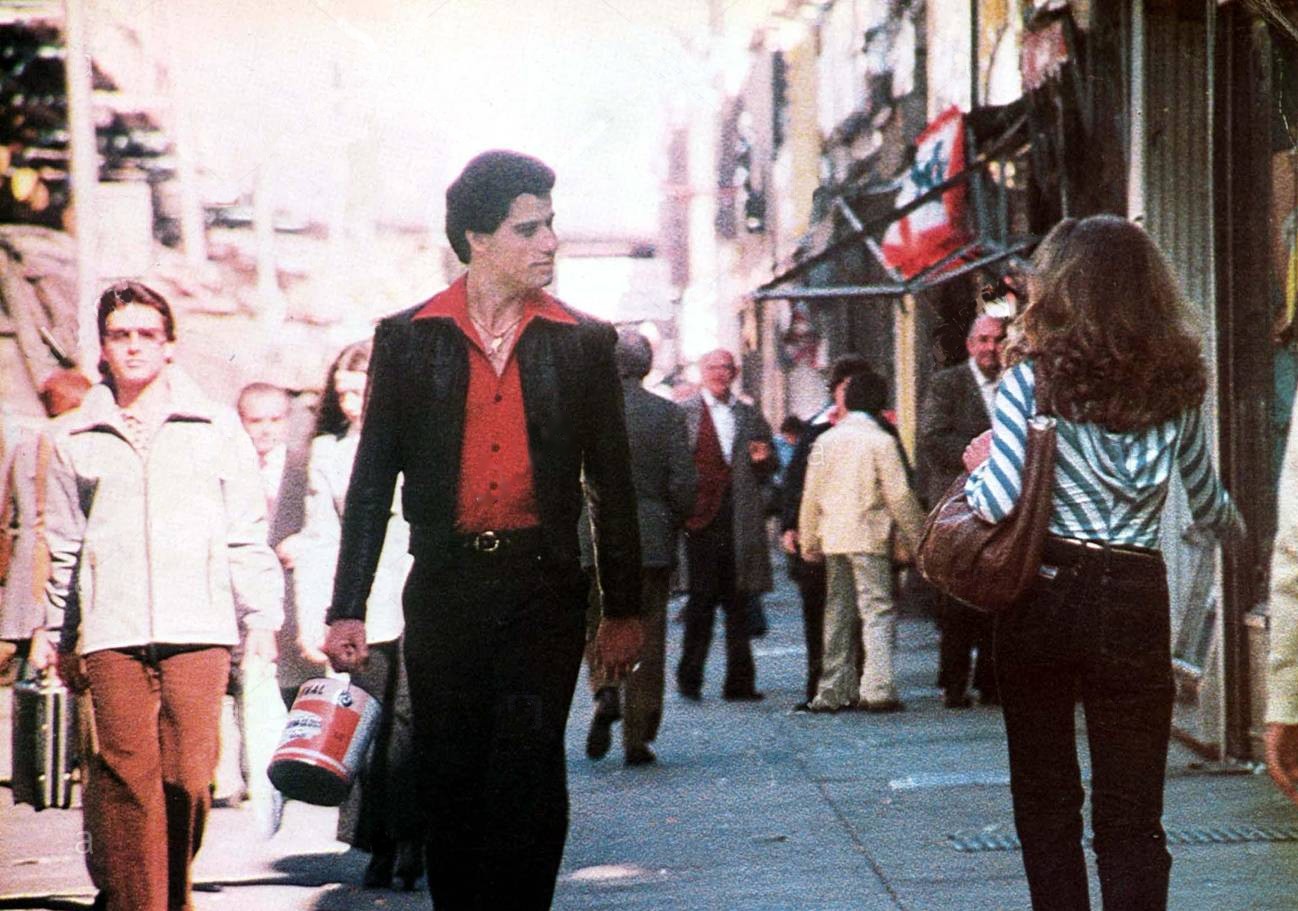

Little Italy

Once again, all these spots were already found years ago, and remarkably, many of the businesses that helped identify these locations are still around today. This includes such institutions as Caffe Roma on Broome, as well as E Rossi & Company on Grand, which has been in business since 1910, making it the oldest gift shop in Little Italy. But like any small business in NYC, its future is always uncertain.

Case in point, the building across from E Rossi & Company —which used house Alleva Dairy— got torn down just a few months ago. I was completely shocked when I saw the empty lot a couple weeks ago, having taken a photo of that corner just last fall when the building was still there.

Alleva Dairy, a 130-year-old Little Italy cheese store known for its fresh ricotta and mozzarella, closed in March of 2023 after a long battle with its landlord over back rent (which was a jaw-dropping $23,756 a month).

Less than a year after the cheese shop moved out, the landlord allegedly had some illegal construction done to the lower levels of the building that undermined its structural integrity. Shortly thereafter, the city ordered the property owners to demolish the building for “safety reasons.” Yet, I feel this could’ve been just an elaborate plan by the owners to get permission to replace a landmark building with a modern structure that will undoubtedly net them more revenue.

Who knows if that’s true. But just goes to show, you never can tell what the fate of a building will be in this crazy city.

Following Sal to Brooklyn

No work was needed on my part in figuring out these Brooklyn locations as ScoutingNY already laid it all out. Although, his descriptions were a bit confusing, making the geography seem more complex than it really was. Essentially, all the action revolved around an unused field in Brooklyn Heights which is now Hillside Park.

I have to admit, I did have to cheat the modern photos of the Bocas switching cars (last two “then/now” images above), standing a bit closer so I could get unobstructed views. In 1971, the shots were taken from Willow Street, replicating the detectives’ point of view. But what was only a barren field back then is now a lush park with trees that block any views of Columbia Heights from Willow Street.

Aside from the development of the parkland, the only real change to the area is the closing of Middagh Street, which reportedly happened sometime in the early 2000s.

Apparently, a tall tractor-trailer on the BQE below hit the overpass, damaging it so much that it was deemed impractical to restore. So the city closed the Middagh bridge and put up barriers and a small green space.

And I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the Federal-style wood-frame house on the corner of Willow and Middagh, which is one of the oldest surviving houses in Brooklyn. While the exact construction date is unknown, historians estimate it was most likely built somewhere in early to mid 1820s, shortly after Brooklyn was incorporated.

You can tell by the front entrance alone that the property has retained much of its 19th century charm, including a Federal doorway with Greek columns, a leaded-glass transom window, and vintage boot scrapers on the wooden stoop. Once operating as a local tavern, the three-story main house is also connected to a two-bedroom guesthouse (converted from a stable) by a sizable walled courtyard.

The Brooklyn Historical Society praised the home as “one of the best reminders of the early days of Brooklyn Heights,” and I couldn’t agree more. It’s a precious gem in a neighborhood that’s already filled with time-honored treasures.

Sal and Angie’s Shop

Even before ScoutingNY published these Bushwick filming locations in 2014, I was fully aware they were featured in The French Connection. The reason being, from 2011-2013, I lived just one block away from Wyckoff Avenue. In fact, the deli on the corner of Suydam —where Popeye makes a u-turn— was one of my go-to shops. It was bit more rundown than the other delis (and often smelled like cat pee), but it was a perfectly adequate place for cheap drinks and prepackaged snacks.

The corner deli eventually closed down as the neighborhood became more gentrified in the mid 2010s. The space is now vacant after housing a gourmet kitchen for about six years.

As to where the cops set up their stake-out of Sal and Angie’s luncheonette, I estimated they were in what is now apartment 2E at 70 Wyckoff Avenue, basing it off the height and angle seen out the window.

Over at 91 Wyckoff, it appears the space was already an eatery when they filmed these luncheonette scenes. It had become a sandwich shop by the time “Dr. Speet” visited the neighborhood in 1986, still bearing a pair of Coca-Cola logos above the entrance.

The retail space has more or less always housed a food business of some kind or another. Although, it’s consistently been Latino-themed since the 1990s when the demographics of the neighborhood began heavily leaning that way.

It’s now a Mexican restaurant called Mesa Azteca which has both indoor seating and outdoor seating in their back patio.

Following Sal to Wards Island

Not much to say about this quick scene on the bridge to Randall’s Island. The one big change was the elimination of the tollbooths in 2017.

There’s now an automatic scanner where the booths once stood, significantly reducing the amount of traffic backups. Definitely one the city’s modernizations of which I wholeheartedly approve.

The Lawyer

This lawyer building was easy to find since it was across the street from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Not much has changed with the residential building, although when Nick from ScoutingNY visited the site in May of 2014, he discovered a pair of statues flanking the front entrance, to which he decried as “the goofiest I’ve ever seen in New York.”

I don’t know the date of when they filmed these brief scenes, but it had to be sometime after November 14, 1970, as that’s when the “‘Masterpieces of Fifty Centuries” show began at the Met. (Its big red banner can be seen in the third “then/now” image above.)

A Bar Bust

This was a location that stumped Nick Carr of the ScoutingNY website, and the suggestions in the comments section were all over place — none of which were correct.

Because the single-take exterior shot quickly pans as the two actors turn the corner from Broadway to Myrtle Avenue, it looked like they were walking on one straight block. That gave the impression that those stairs to an El station were in the middle of the block (something that is very uncommon).

This misconception of the stair placement caused a lot of the problems in figuring out the filming location. But the most valuable clue was the sign above the bar, which seemed to say Duplex Bowling

So, all I had to do was look up the name in a 1971 Brooklyn phone directory at the 42nd Street Public Library and get an address. Turns out, Duplex was located on the second floor of 1128 Myrtle Avenue. The building has since been demolished, so it was hard to verify, but one thing was consistent — it was right next to the stairs to an El station.

About a year after I got the bowling alley address, the NYC Municipal Archives released all of their 1940s tax photos, allowing me to grab a picture of the location. And once I sew matching stones and a bowling alley sign (even though the name was Schumacher back then), I knew I had accurately found the right place.

In retrospect, it’s kind of funny reading some of the suggestions that were being made in the ScoutingNY comments section back in 2014. Things even got a little snarky, with each party smugly confident they were correct, when it’s clear now, neither were correct.

As I already mentioned, the building got torn down years ago. It is now a Popeye’s Chicken, which is wonderfully appropriate.

Devereaux Arrives in New York

This location was already identified when I started tackling The French Connection, but it wouldn’t be too hard to find considering the scene has informative vista views of Lower Manhattan.

What used to be a shipping yard and entry point for immigrants, is now part of the sprawling Brooklyn Bridge Park. What’s nice is, the developers of the park made sure to keep a few remnants of the old shipping days in place, such as the framework of the large pier shed (which now houses a large playing field) and one of the original moorings.

Plus, the NYC Ferry system has a stop there, giving you direct access to Wall Street or Governors Island.

Picking Up a Bicyclist

The bar’s location was given on the ScoutingNY website, but it didn’t specify where Popeye picked up the bicyclist or what apartment he lived in. The cyclist was clearly on the nearby Cherry Street, based on the Manhattan Bridge in the background, and the specific apartment was found by zooming in on the door, which had 5E on it.

The brief scene of Popeye leaving the bar was part of a much longer sequence that began in the evening. The first scene involved Gene Hackman improvising a conversation with a bunch of actual ex-cons, discussing old pugilism schemes.

The bartender was another non-actor, who went by the name “Fat Thomas.”

Fat Thomas was a retired bookmaker who still had connections to the New York underworld, and according William Friedkin, was instrumental in finding several of the locations used in the movie.

At the time they filmed these scenes, this South Street water hole was officially called Bar 100, nut was better known as Mutchie’s, referring to the owner and bartender. Often a popular destination for local fishermen and longshoremen, Mutchie’s was also frequented by pressmen and reporters, mostly coming from The New York Post, whose building was just a few blocks north.

I’m not sure exactly when the bar was torn down, but by my estimations, it was somewhere between 1980 and 1984. Today, the corner lot is part of Murry Bergtraum Softball Field, named after a former president of the NYC Board of Education.

Tailing Sal Across the Brooklyn Bridge

As expected, you can see a few new skyscrapers in the background that have sprouted up since the seventies. Another significant change is on the bridge itself, which now has a protected bike path on the same level as the cars. The path used to be up on the wooden walkway, forcing pedestrians to share the space with speeding cyclists, often making it a crowded and sometimes hazardous experience. Now, as a pedestrian, all you have to contend with are slow-moving gawking tourists.

Tailing Sal in Midtown Manhattan

Most of the locations in these sequences were found through the benefit of street and retail signs, including the 1924-established Roosevelt Hotel between E 45th and E 46th Streets. The hotel has been a filming location for several productions, including the 2010 thriller, Man on a Ledge, which I worked on for several weeks as an extra in the crowd.

It’s hard not to recognize the building, thanks to the distinctive swirls in the antique marble on the ground floor (reportedly imported from southern France).

After being in business for nearly 100 years, it was announced in 2020 that the hotel would be closing, due to financial losses caused by the pandemic. It reopened in 2023 as a shelter for migrant asylum seekers, but Mayor Adams just recently stated that the controversial center is scheduled to shut down this coming summer.

And now, the feeding frenzy among commercial developers begins.

According to The New York Post, the property’s owner is putting the building up for sale and is seeking upwards of one billion dollars from prospective buyers. And with no landmark status, that would mean a developer could tear down the historic hotel and build a towering skyscraper of up to 1.8 million square feet, taking advantage of the city’s recent rezoning rules.

Tailing Charnier to a Restaurent

Like that Alleva Dairy building in Little Italy, the deli building Charnier goes into in the first “now/then” image above was there one day and gone the other.

Truth be told, when I visited 940 Second Avenue in 2022, the building was already surrounded by sidewalk sheds (more commonly referred to simply as scaffolding), so I had I feeling its days were numbered.

Fortunately, over on First Avenue, the restaurant and surrounding buildings are still intact with no immediate plans for demolition. And to my surprise, the current restaurant at 891 First Avenue —Copinette Restaurant & Bar— has fully embraced its link to The French Connection.

They recently hosted an anniversary party of the film’s premiere, screening the film and serving French prix fixe specials at close-to-1971 pricing.

They also have a plaque on one of their tables, commemorating the movie.

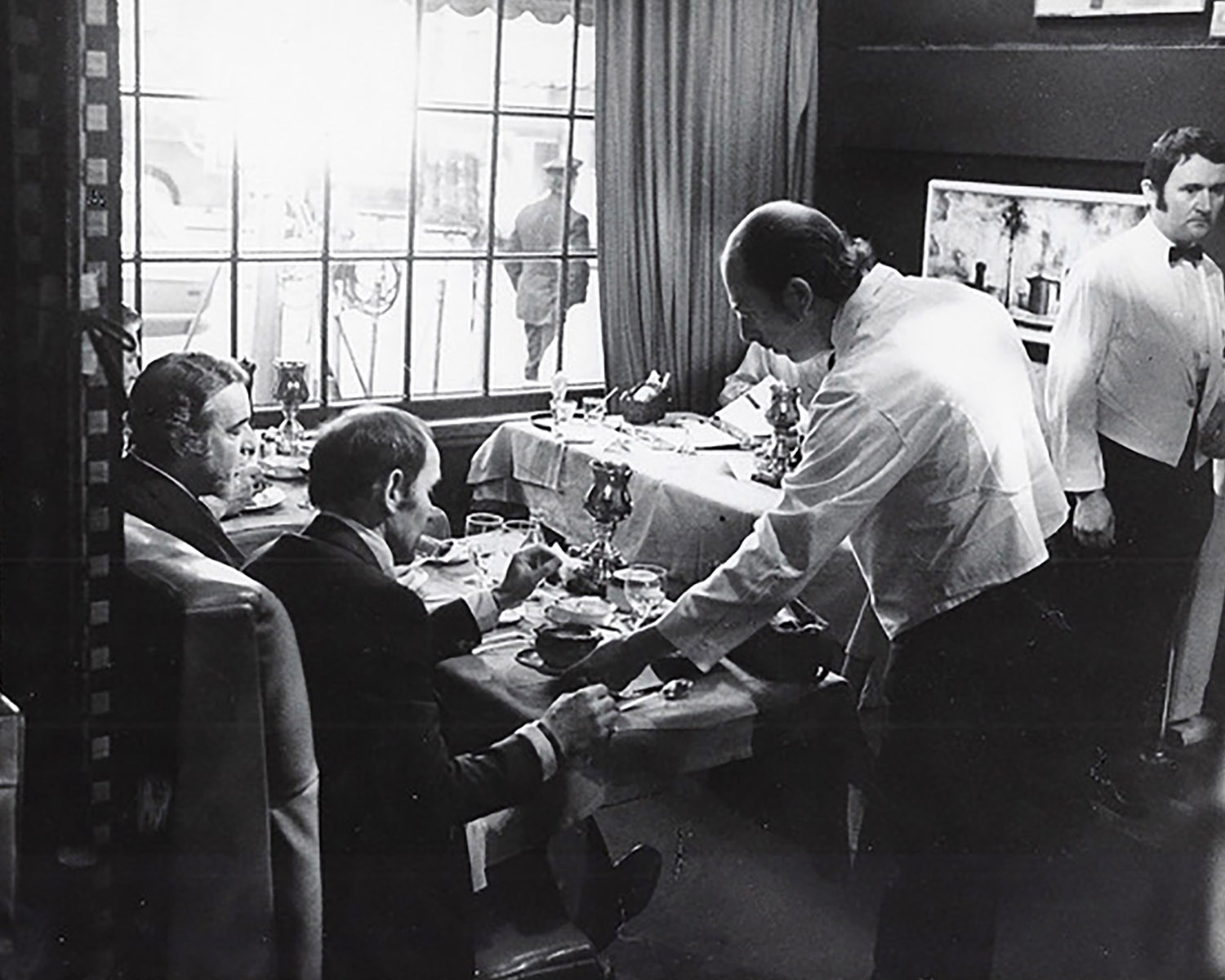

At the time this movie was being made, the space was a French bistro called the Copain, which had been in business since 1945. The restaurant was started by an ex-navy man named Ed Kerns, who developed a taste for French food in his travels abroad. The menu was full of the old-school classics, such as frogs legs, escargot, chicken a la king, rolled roast beef tenderloin, and shellfish platters.

Apart from fine food and wine, the Copain also offered something else that appealed to its affluent neighbors — delivery — a service that was fairly unusual back in the 1940s.

While the Copain already had a solid reputation before its cameo in The French Connection, the restaurant became even more fashionable after the movie’s release and subsequent Oscar wins. It’s been said that the table where the actors sat became the most requested seat in the house.

I think what’s most salient about the scene at the Copain is the stark dichotomy being shown. As the drug smugglers are served sliced boeuf and French press coffee, the blue-collar cop has a pizza slice and cold bodega coffee in the freezing cold. Given those two options, most people would probably choose the life of the criminal.

As much of a boost the movie provided for the Copain, it wasn’t enough to secure the restaurant’s popularity forever, and the upscale bistro was gone by the time the 1980s rolled around.

At that point, a BBQ joint called Wylie’s moved in and ended up having a solid 14-year run at that address. After that, the space saw a variety of cuisines come and go before finally sitting vacant from around 2015 to 2018.

Today, the current restaurant, Copinette, serves American cuisine with a French influence, boasting on their website that they’re continuing the story where Copain left off — “honoring the history of this space but telling its story from a different perspective.”

And any business that embraces its connection to a classic movie always puts a smile on my face.

Tailing Charnier to His Hotel

These hotel scenes were filmed at the former Westbury in Lenox Hill, which when I first took pictures of it in March of 2025, was covered in scaffolding. But thankfully, the building was mostly clear when I returned a few months later in late-summer.

The Westbury, situated on the corner of Madison and E 69th, was first built as an apartment house and hotel in 1927 with about 65 percent of the rooms for transients. Post-WWII, the clientele of the 334-room hotel began to change more towards society-types, thanks to its proximity to museums, boutiques and Central Park.

As the years went on, the Westbury attracted a healthy share of celebrities, with Joan Rivers, Sidney Poitier, Nancy Reagan, Anthony Quinn, and Richard Nixon all being guests at one point. Both Liza Minnelli and Al Pacino were once residents of the chic Upper East Side hotel, the former of whom often requested the kitchen tenderize lean ground beef for her dog.

The Westbury Hotel closed in 1997, and the building is now solely condominium apartments. As to the ground floor where the lobby scenes were filmed, the space has since become a super exclusive members-only club called Maxime’s.

It’s one of those places that makes me cringe just to think about — filled with judgmental staff and pretentious Upper East Siders wearing outfits that cost more than a used car. Described in a recent NY Post article: “It’s very British. And you need a jacket. And no tables of more than four people of the same sex.“ Sounds like a breeding ground for every John Hughes movie villain.

Naturally, with such a private space, I couldn’t get any modern photos other than a fleeting view taken through a crack in their curtains.

My hope is that Maxine’s will be a flop and the space will eventually be converted into something that doesn’t require a jacket and a seven-figure bank account to pass through its velvet-roped entrance.

Tailing Charnier From His Hotel

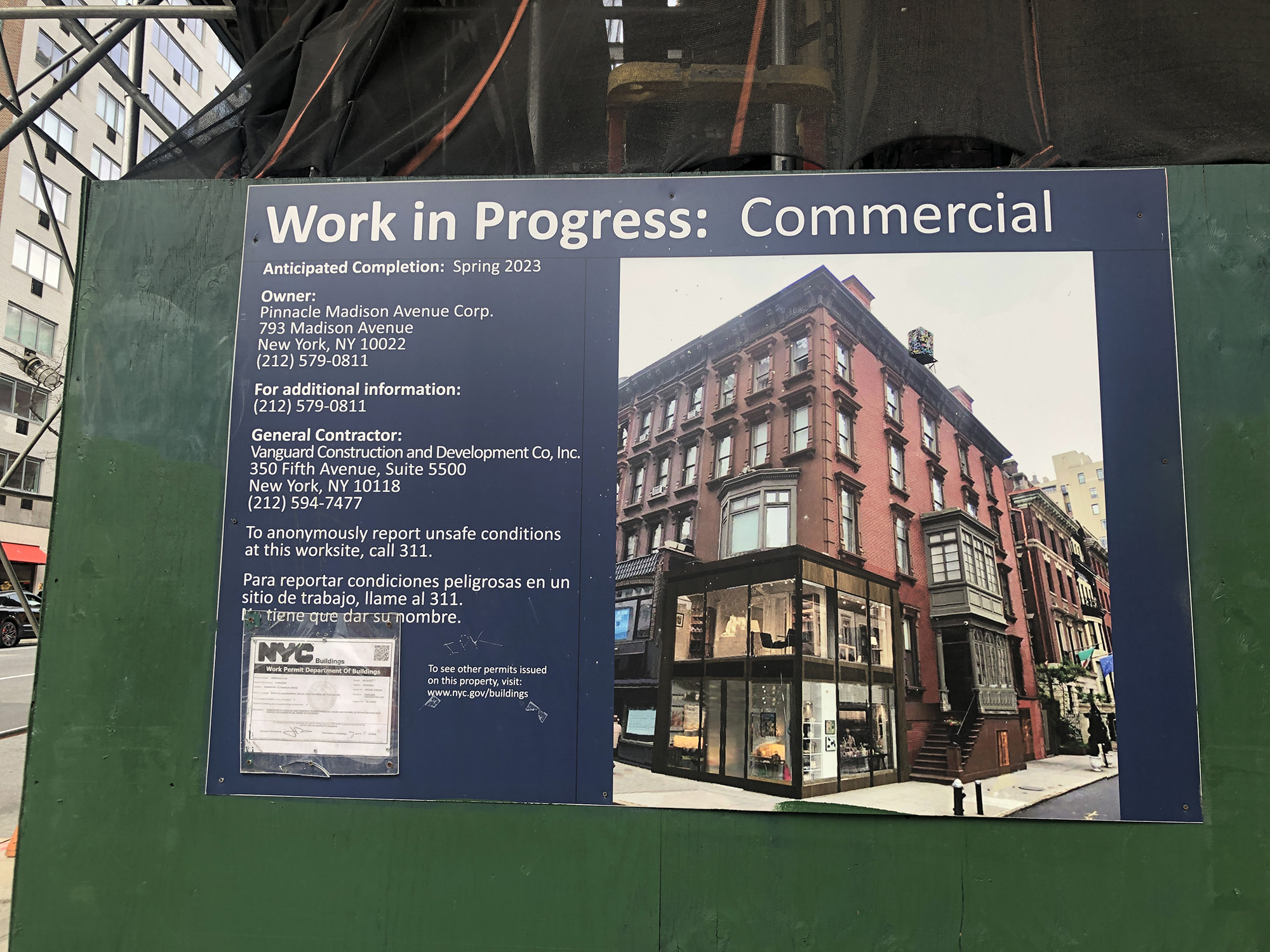

I can’t tell you how dismayed I was when I discovered the lower shop on E 67th street was covered in sidewalk sheds. The bad news: all that plywood and steel piping mucked up my modern photos. But the good news: it appears the building is only being repaired and isn’t slated for demolition.

Based on a rendering posted at the site, it appears the building is getting restored and upgraded for a more open commercial space. (It also appears they’re behind in their work as the estimated completion date on the sign was spring of 2023, and as of this writing, the building is still shrouded in construction apparatus.)

Regardless, it’s nice to know that this five-story, Neo-Grec building from 1881 isn’t going anywhere.

Fortunately, most of the other filming locations along Madison Avenue are still around and unencumbered by scaffolding. A lot of the buildings still have recognizable details from the movie, but one glaring change happened on the corner of 68th where Hackman leans up against the building.

The corner building was built in 1882, but its facade was dramatically altered by 1971, creating a sort of futuristic design on the lower levels.

This was more or less reversed in the 1990s and the ground level now looks more like its original 19th century design.

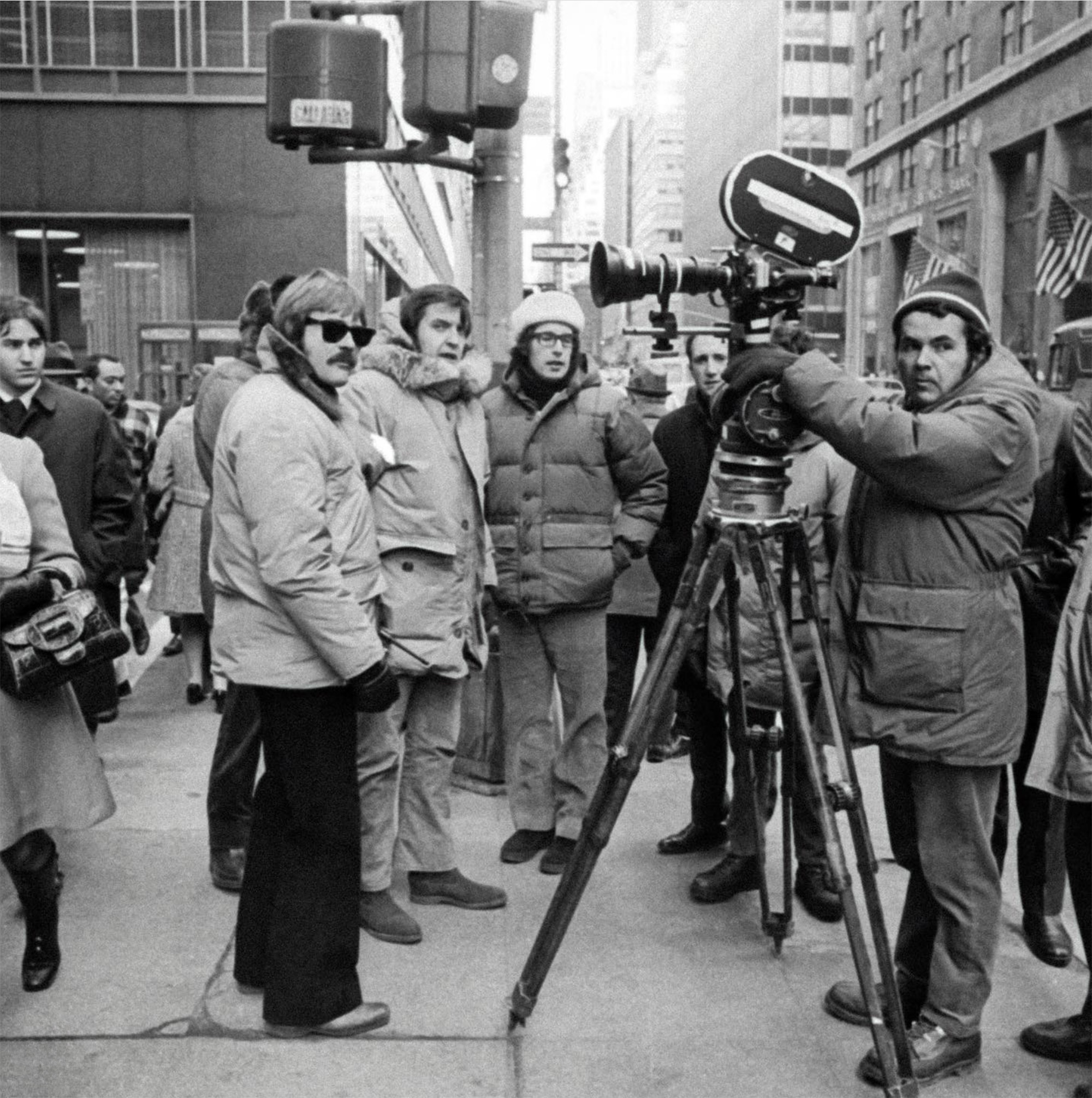

Amazingly enough, for all these scenes on Madison Avenue, production decided to shoot it without any extras. As told by cinematographer Owen Roizman in a 1972 interview:

The assistant director was worried about people looking at the camera, so we talked about hiding the camera, camouflaging it, or shooting out of cars. The day we went out to shoot, I said to him: ‘Let’s try to shoot without any coverup. Let’s just put the camera out on the street, hand-held or on a tripod, and see what happens.’ I had the feeling that New Yorkers were so used to seeing newsreel cameramen running around that they would pay no attention. Sure enough — it worked! We even got so brazen as to set up a 12-foot parallel right on the sidewalk in the busiest section of Madison Avenue, and nobody looked at the camera.

Typical New Yorkers — too busy to give a rat’s ass.

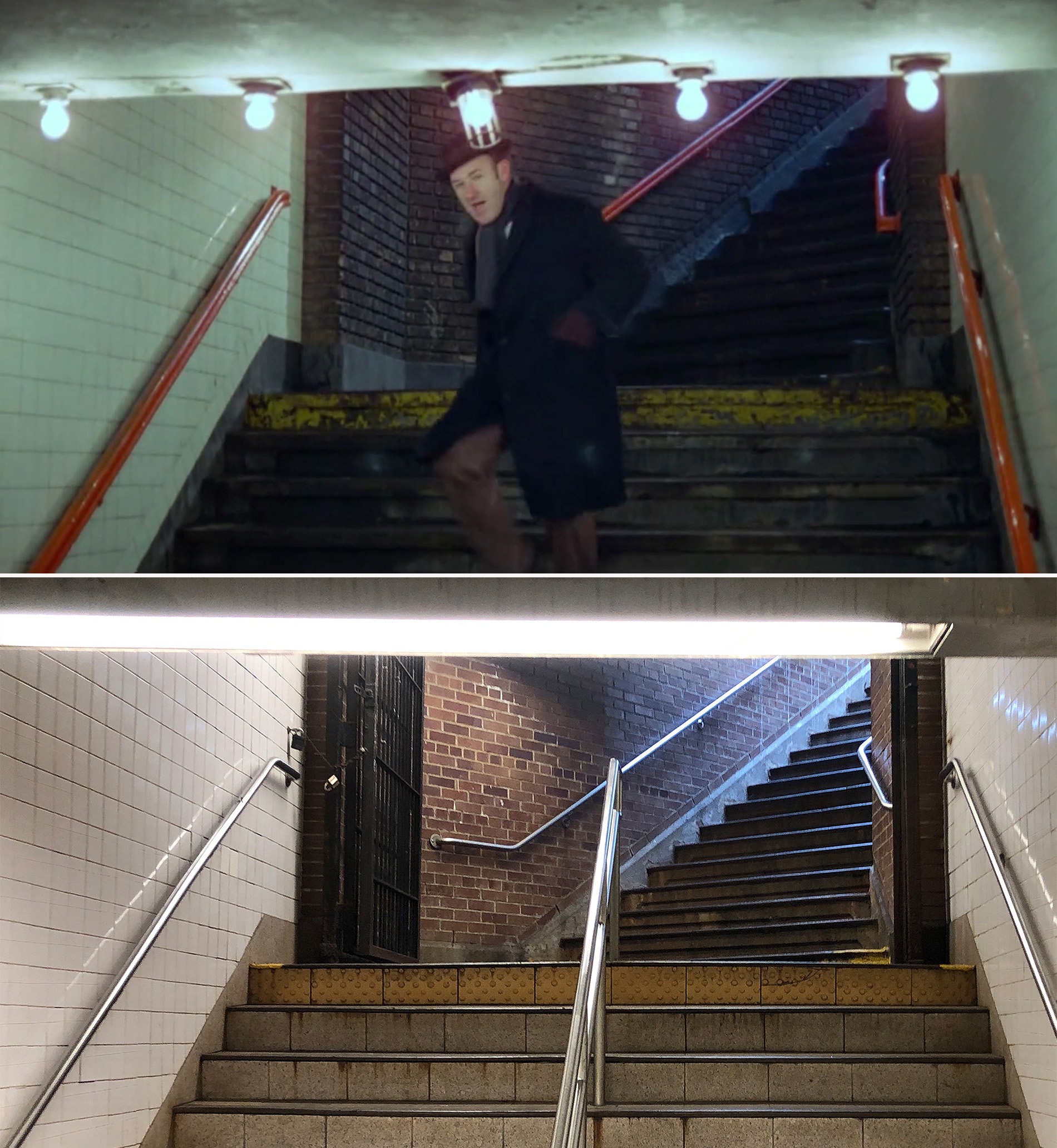

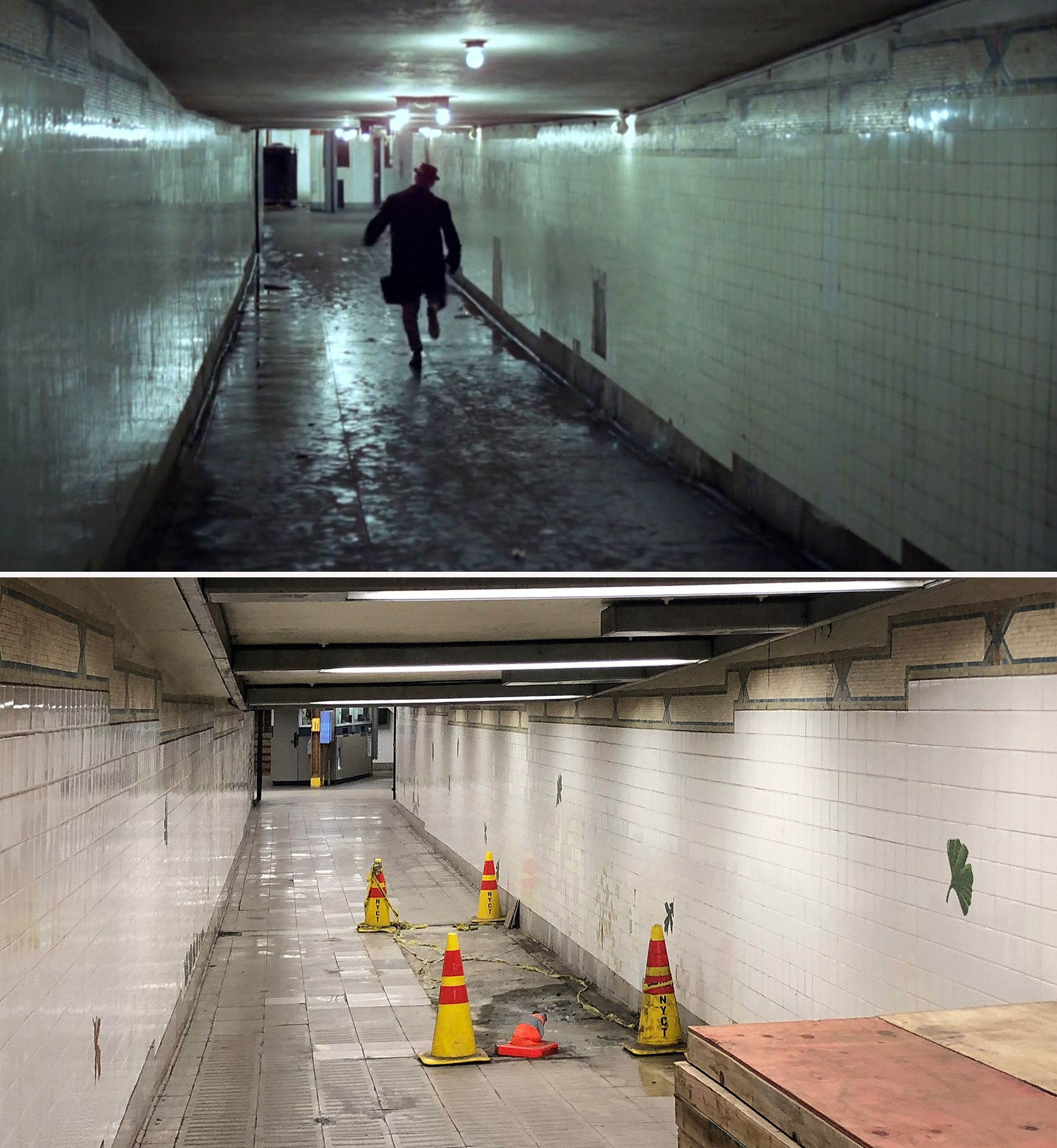

Subway Cat and Mouse

Both of these subway locations were easy to identify, thanks to concrete visuals outside the 5 Av/59 St station entrance, and signage inside the 42nd Street shuttle station.

Aside from the well-choreographed, heart-thumping game of cat and mouse on the platform, the best thing about the scene at 42nd Street is the presence of of those kitschy refreshment stands on the platform.

Not sure when those carnival-style booths were removed, but they lasted until at least the mid-1980s.

After their removal, the next big change to the station happened in 2020-21. That’s when the shuttle system was upgraded and the center track (number 3) was eliminated from service.

Meeting in Washington DC

The Washington DC locations were easy to find thanks to the well-defined landmarks in the area, such as the Washington Monument and the United States Capitol.

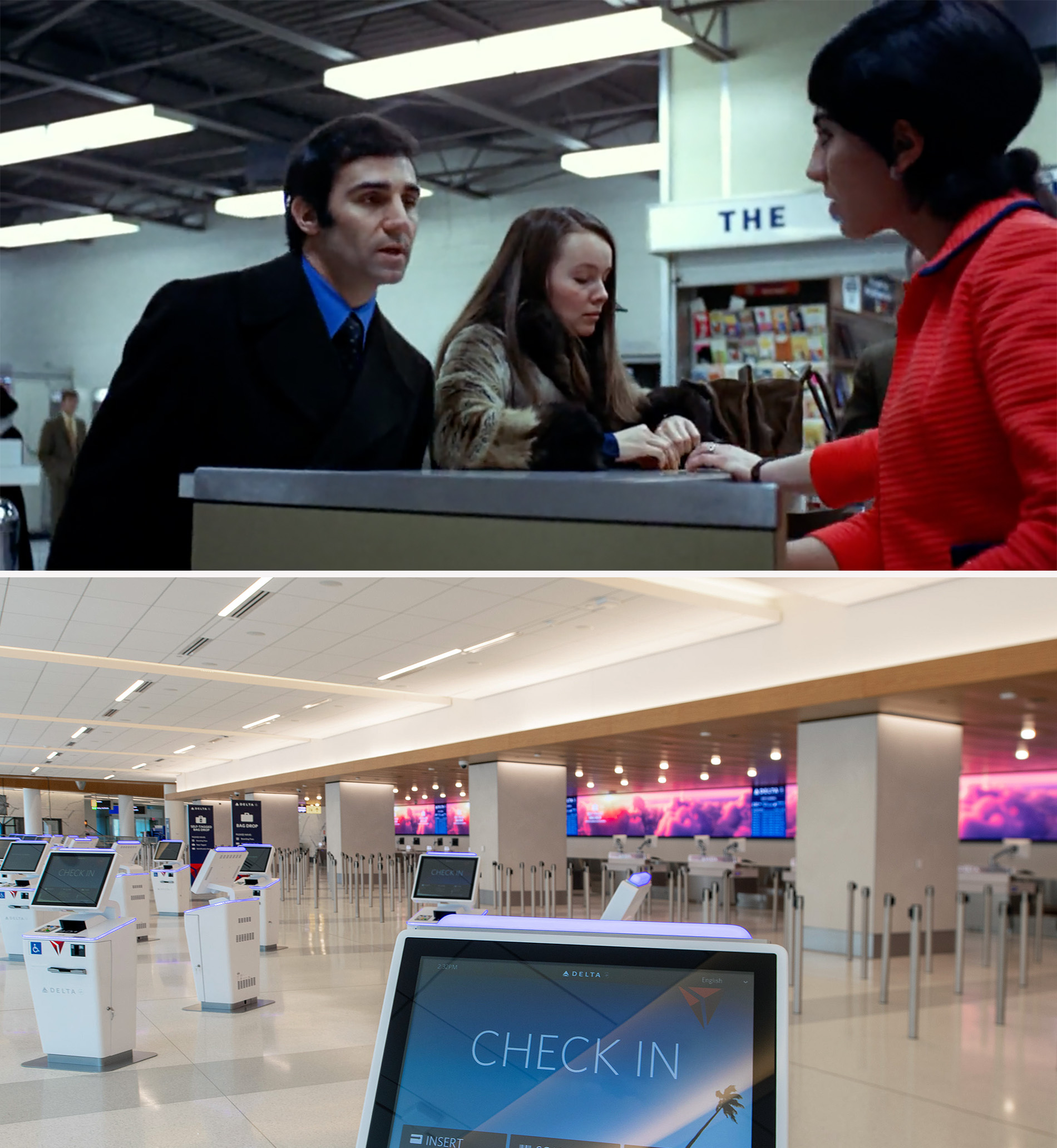

As to the airport, since the characters were taking an Eastern Air Lines Shuttle, I deduced they filmed the scene at LaGuardia, which was the only NYC airport where Eastern offered that service.

I had a little trouble figuring out what terminal was used and where it was located, so I asked Blakeslee to lend a helping hand.

First, he and I were able to determine that the air shuttle ran out of a facility inside the airport’s Hanger 8. Next, Blakeslee was able to dig up a couple period maps that gave us a basic idea of where that hangar used to be on the property.

Blakeslee then estimated the scene took place approximately where LaGuardia’s Terminal C now is. Built in the early 1980s, Terminal C is partially used by Delta Airlines which offers a similar type of shuttle service to DC — but at a considerable higher rate and a lower amount of convenience than depicted in the movie.

Back in the day, when Eastern was offering shuttle service to Washington from LaGuardia, getting a ticket was a quick and painless process. Beginning in 1961, the Shuttle ran frequently each day, with virtually no security check, no reservations necessary, and the option to actually buy a ticket aboard the plane. It was basically like catching a crosstown bus.

Eastern Air ended its shuttle service in 1989 when the company was sold off, eventually ending up in the hands of (the now-defunct) USAir. Nowadays, the idea of a hassle-free air shuttle to nearby cities is an unheard-of service from a bygone era.

Progress.

Popeye is Off the Case

Of all the exterior locations from this movie. this was the most difficult one to get to in person.

Situated near an exit on the Henry Hudson Parkway in the Bronx, the roadway was technically off-limits to pedestrians. However, I was able to reach it by taking the Old Putnam Trail in Van Cortlandt Park, skirting through the northern part of the park’s golf course, then cutting through some brush along the parkway.

I couldn’t match up any of the trees from the scene, but I was able to line up the inapt fire hydrant amongst the overgrown plants and wildflowers.

An Assassination Attempt

This location was identified decades ago, and was included in Dr. Speet’s French Connection photo album from the mid-1980s.

I can only assume Popeye’s apartment building was initially found due to its close proximity to the Bay 50 St Station, which appears in the next scene. Plus, this was the only housing complex of its kind in the entire neighborhood.

Officially called the Marlboro Houses, this public housing project was built in the 1950s on what was then large vacant lots. The Marlboro remains to be the only NYC Housing Authority project in Gravesend, which is mostly a working-class neighborhood just to the north of Coney Island. Like many NYCHA projects, Marlboro Houses has been criticized for interrupting the continuity of residential and retail corridors, essentially forming an island that is isolated from the broader community.

While some of the criticisms can be a bit hyperbolic, when you visit any of these types of housing projects, you do feel like you’re entering a separate neighborhood of its own.

Like much of Gravesend, the Marlboro Houses haven’t changed a whole lot since 197i, although the entrances have been updated and some of the trees are now gone. (Interestingly, one of those trees that’s gone today was actually still around when I visited the site in 2017.)

Taking pictures on these types of properties are always a little tricky since many of the residents are on Public Assistance programs and can be sensitive to being photographed. But thankfully, all three times I visited the site, there were not a lot of people around, so I had no direct issues.

I thought getting inside the building itself was going to be an issue, and getting onto the roof to be impossible. But like the situation at 100 Old Slip, I got extremely lucky, and when I pulled at the front door, to my surprise, it opened right up.

The luck continued on the inside as I climbed the stairs to the top level, tried the door, and discovered it to be unlocked, giving me exclusive access to the rooftop.

I’m not normally a believer in the supernatural, yet I couldn’t help but think that maybe the spirit of Hackman was providentially helping me gain access to these normally inaccessible locations. Nonetheless, it was another unexpected adventure, and a real thrill to see this elusive location in person.

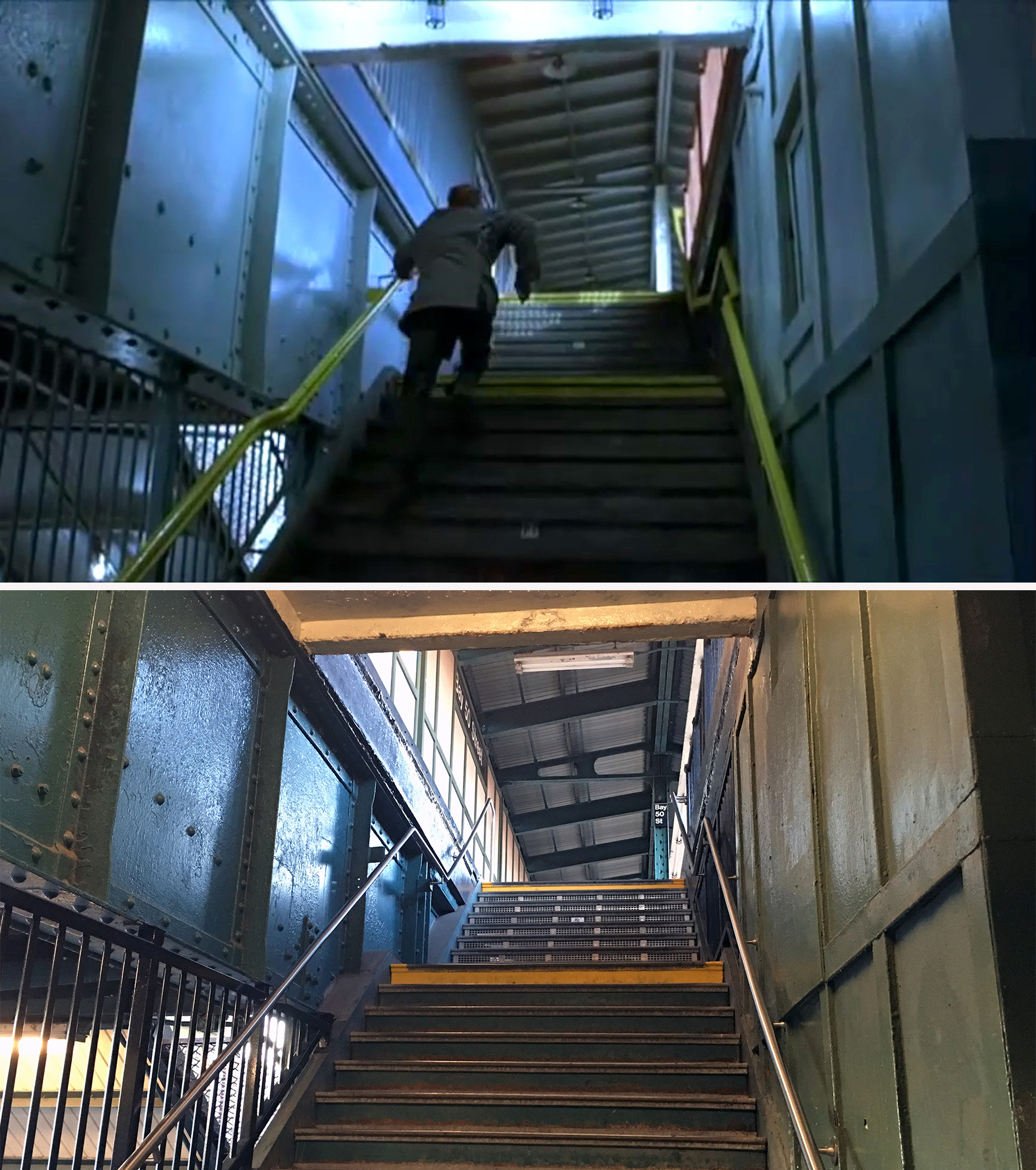

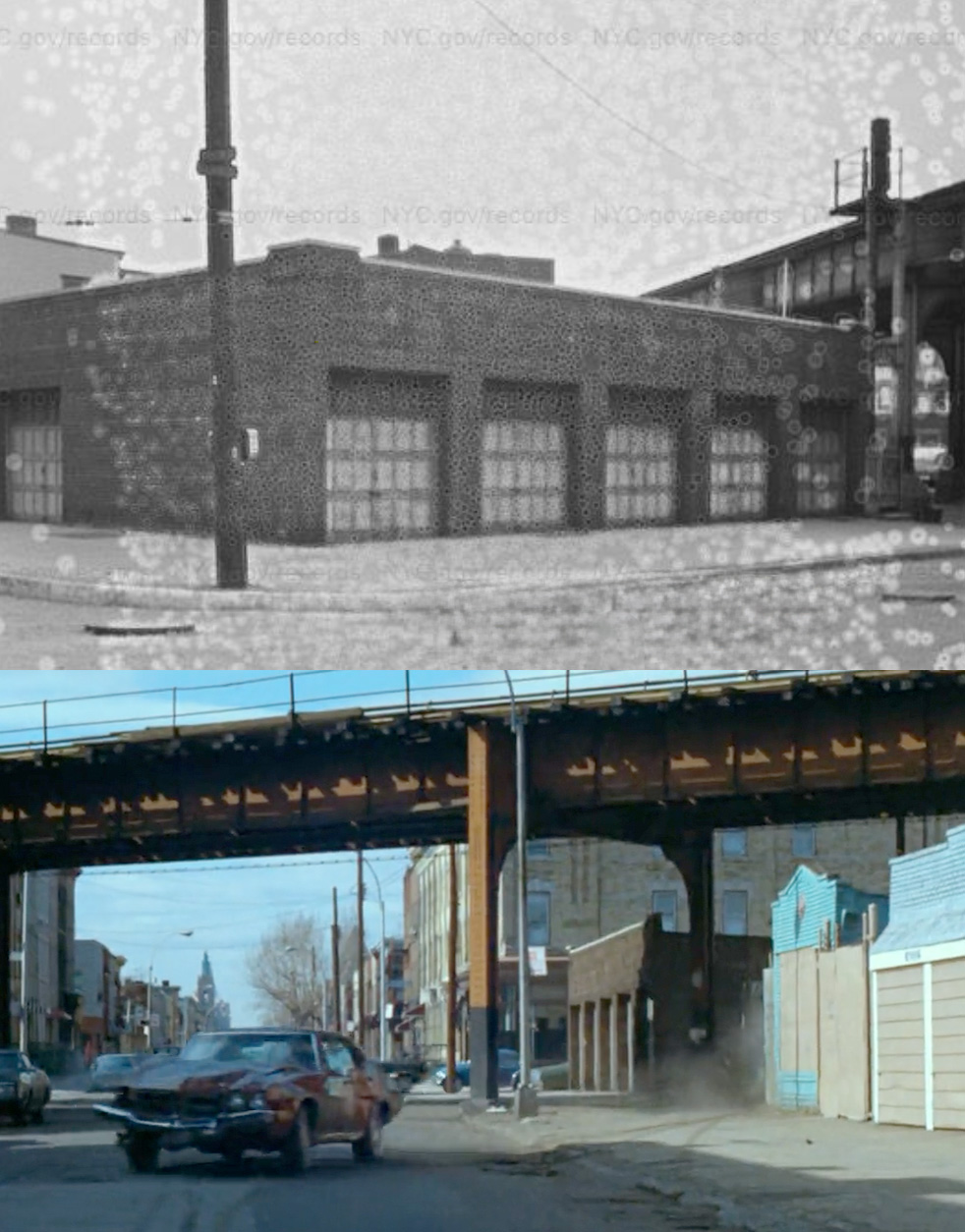

Nicoli Escapes Onto an El Train

Train vs Car Chase!

Popeye Kills Nicoli

Okay, whew! That was certainly a lot. And there were still a couple spots on the street I didn’t cover, not to mention most of the stuff on the El train.

Many film books and websites have covered the locations of the beginning and end to this frenetic chase sequence, but they often leave out most of the places in the middle. The ScoutingNY website highlighted a couple spots along the way (like the part with the baby carriage), erroneously concluding that the sequence was mostly shot in geographical order. But as you might’ve noticed in all my descriptions above, there were numerous deviations in the path from the Bay 50 St Station in Gravesend to the 62 St Station in Bensonhurst.

Finding all the specific spots in Brooklyn was fairly straightforward since they were all located in between the starting and ending points. I simply traveled up and down the route in Google Street View, searching for matching structures. It was a little time-consuming, but overall, a fairly painless process, thanks in large part to the fact that this section of Brooklyn hasn’t changed a whole lot over the decades.

While a portion of the neighborhood is middle- and upper-class, it’s primarily made up of working-class people, so there’s been less of a push by developers to upgrade the retail/residential buildings along the El tracks. Consequently, much of the street looks like how it was back in the seventies. (It might be noted that the same tracks were featured in the opening sequence to another 1970s classic, Saturday Night Fever.)

When it came to the section of the chase taking place in Queens, once again, my nomadic lifestyle in NYC afforded me some personal knowledge in identifying the filming locations.

The big clue was the part where Hackman is paralleling the elevated tracks that appear to be cutting through the middle of the blocks — a fairly uncommon occurrence in the MTA system. Having lived in Queen’s Ridgewood neighborhood for two and a half years, I was familiar with a portion of the nearby BMT Myrtle Avenue Line that was laid out that way, cutting though the blocks in its approach to the Forest Av Station.

Once I confirmed the Putnam Avenue location by matching up the apartment buildings, I was able to the figure out that the scene where Popeye slams into a fence under the tracks was on the nearby Onderdonk Avenue. (The avenue was undoubtedly named after the Onderdonk family, who were outspoken patriots during the American Revolution, and whose historic c 1709 house at 1820 Flushing Avenue remains today).

The fence-crashing site has changed a lot over the years, but I knew it had to be the right place based on that very unique track layout. But wanting to confirm things with some visual proof, I ended up matching things up with some 1940s tax photos.

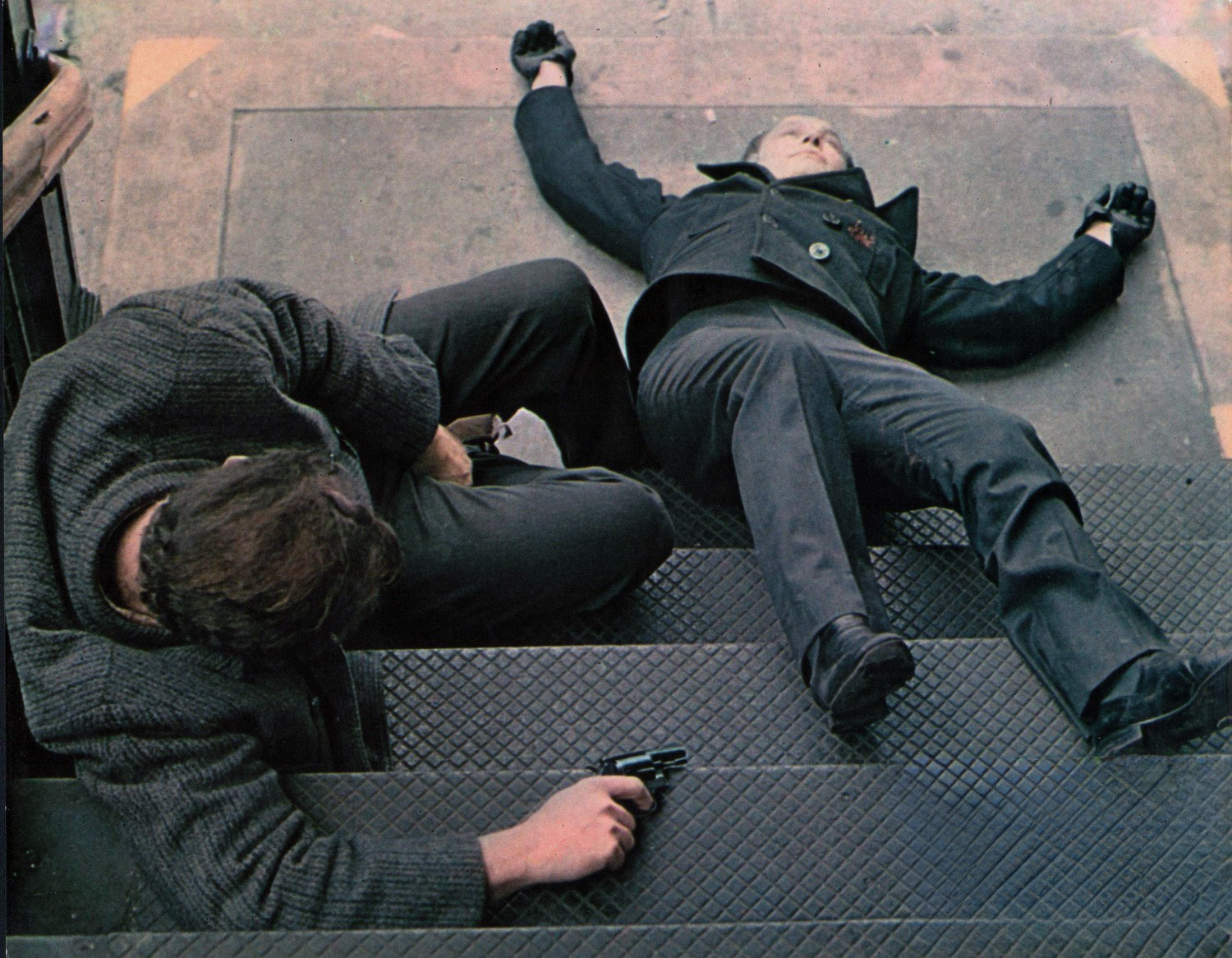

The death scene at the end of the sequence is probably the most iconic moment from The French Connection. An image of the infamous shot in the back was even used as the main motif for the marketing material, including its gutsy poster.

Being such an iconic scene, its location has been known for a long time. Countless movie fans have visited the site to capture the steps where the French assassin gets his deadly comeuppance (despite the fact the stairs themselves have been replaced since 1971).

Another fan of the film was most assuredly Matthew Harrison, who directed the 1997 indie film, Kicked in the Head, and staged a gun shoot-out at the very same spot.

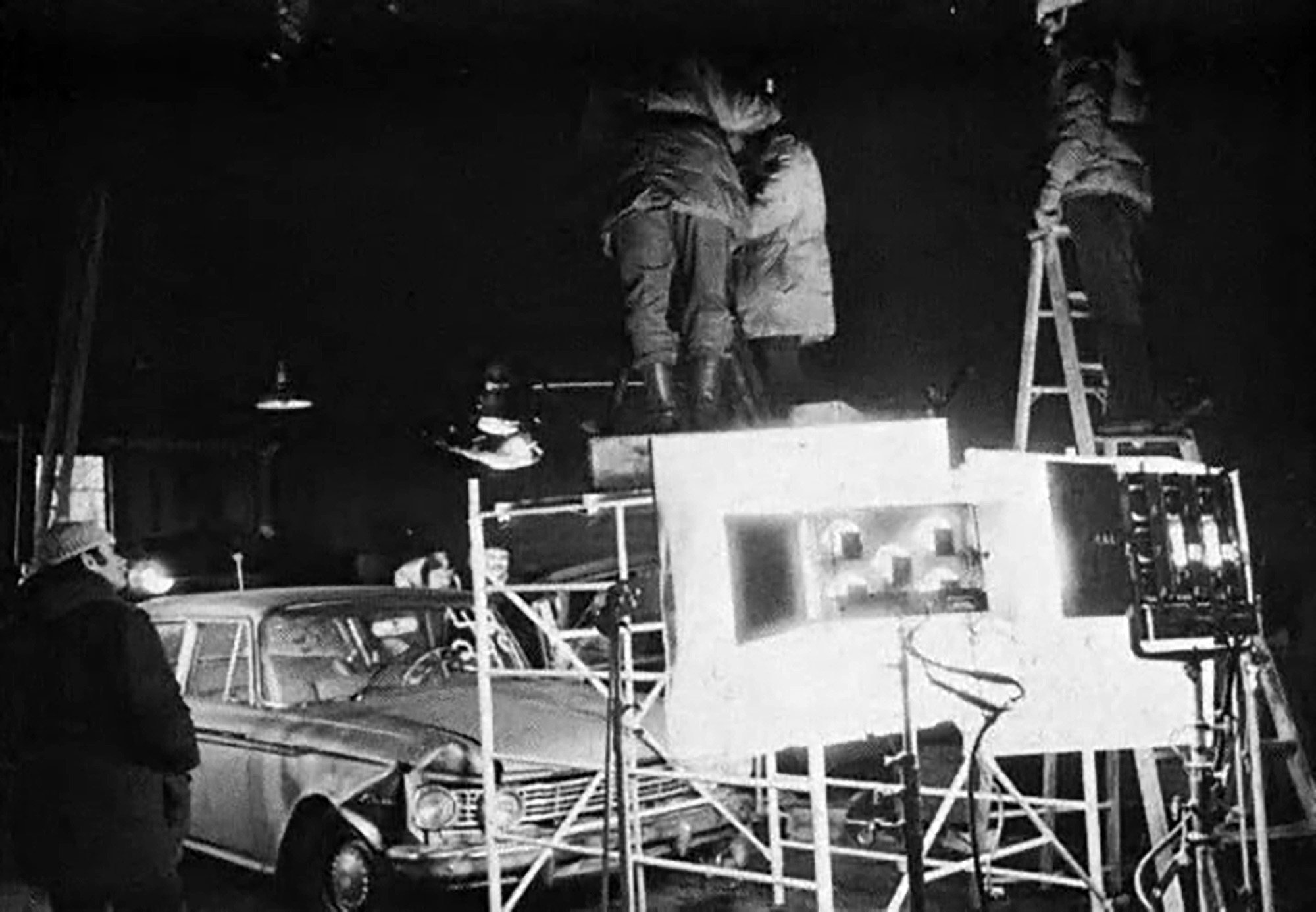

In total, this extended chase sequence took 5 weeks to film, and contained a few mishaps here and there, including a local driver accidentally sideswiping the picture car with Gene Hackman at the wheel.

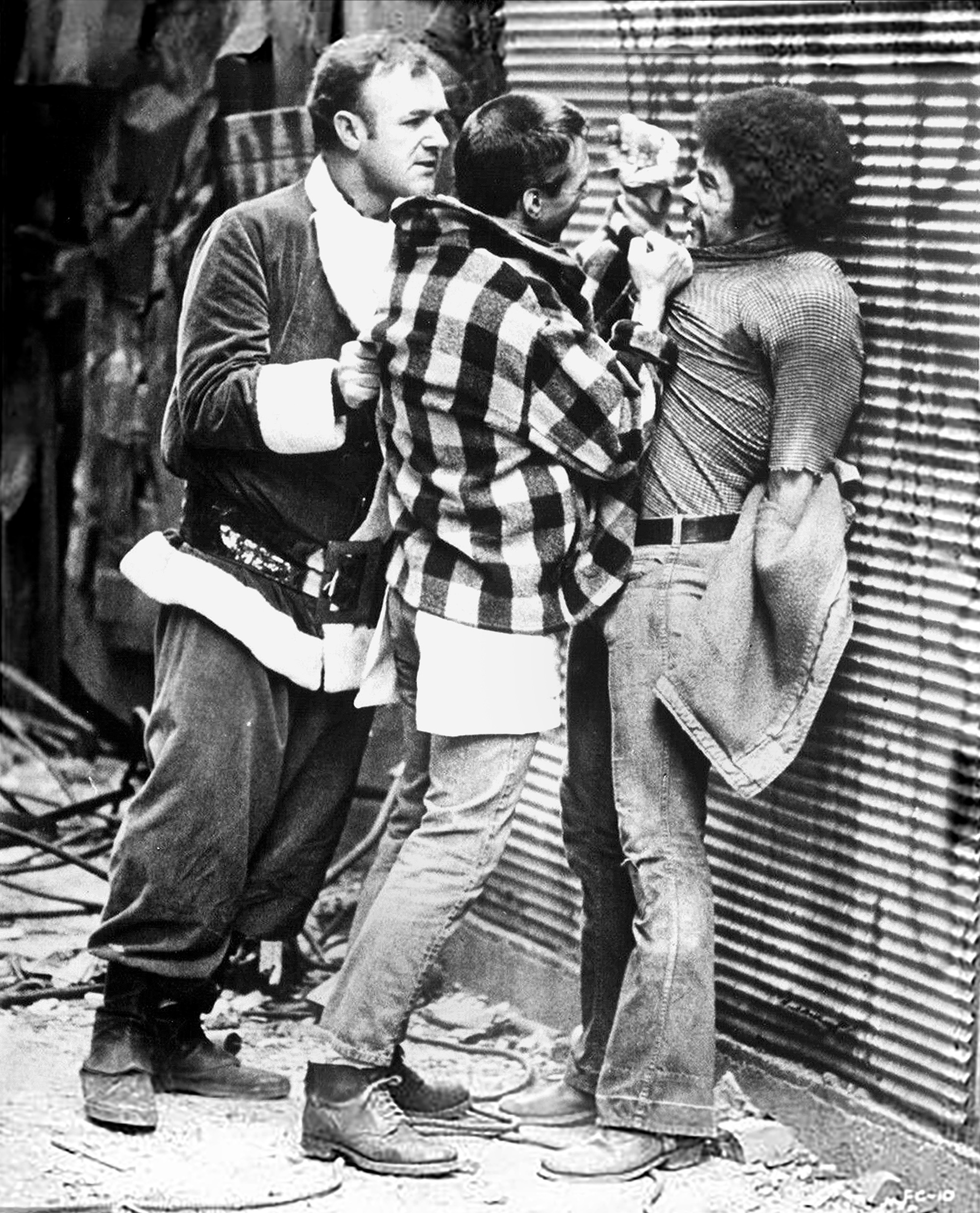

While a lot of the movie was shot “guerrilla style” —grabbing shots on the sly without any permits— this car chase sequence was in a quasi-controlled environment. With help from the NYPD, production was able to block off sections of the street while they filmed certain parts of the chase, protecting the area with stunt cars.

Unfortunately, the one thing the crew and police didn’t count on was that some of the residents who had cars parked inside those blocked-off areas would have to leave during the filming. And as the story goes, one of those residents unknowing entered the active “set” and smashed into the brown Pontiac LeMans, sending the vehicle into a support post for the El tracks.

Fortunately, no one was seriously injured, and production had back-ups of the LeMans, so it ended up being just a minor hiccup. But production did end up having to pay for the damages to the local driver’s car.

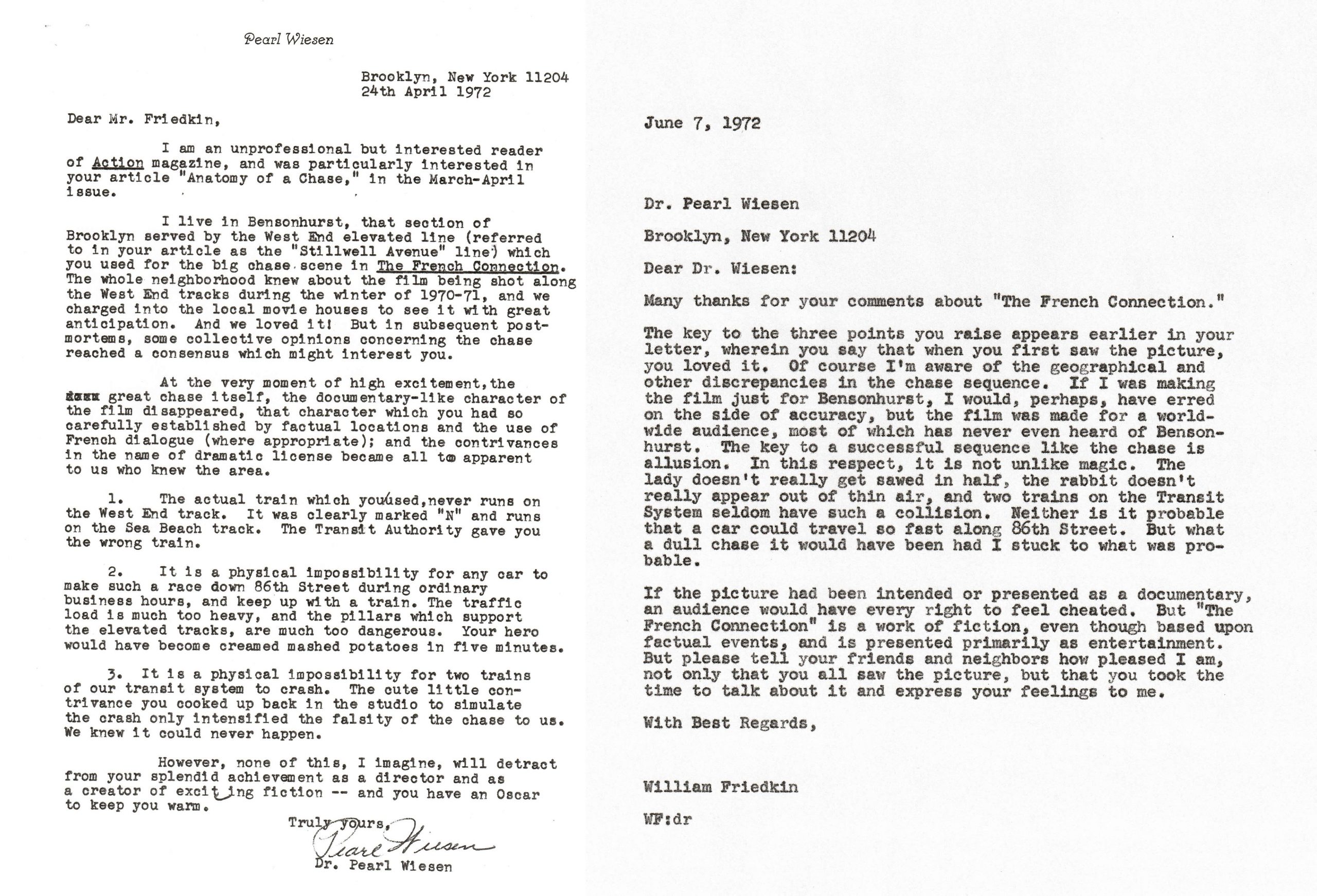

After the movie was released in theaters in October of ’71, this chase sequence was obviously a thrilling highlight for moviegoers. But that still didn’t stop a few sticklers from pointing out some of the errors and inconsistencies. Below is one of those letters and director Friedkin’s response. (Click to enlarge.)

I guess that was the 1970s version of leaving a negative comment on a social media feed.

Parking Garage

South Street Seaport

Once again, the locations from this sequence —going from the parking garage to the South Street Seaport— were previously identified by others.

While there have been a few changes in the waterfront area —most notably the area under the bridge changing from a auto dumping yard to a fenced-off supply area for the DOT— there’s still an overall timeless quality to Dover Street.

What helps give it that timeless quality is the lack of traffic — both foot and vehicular— keeping things fairly quiet and isolated. Definitely one of my favorite places to walk around.

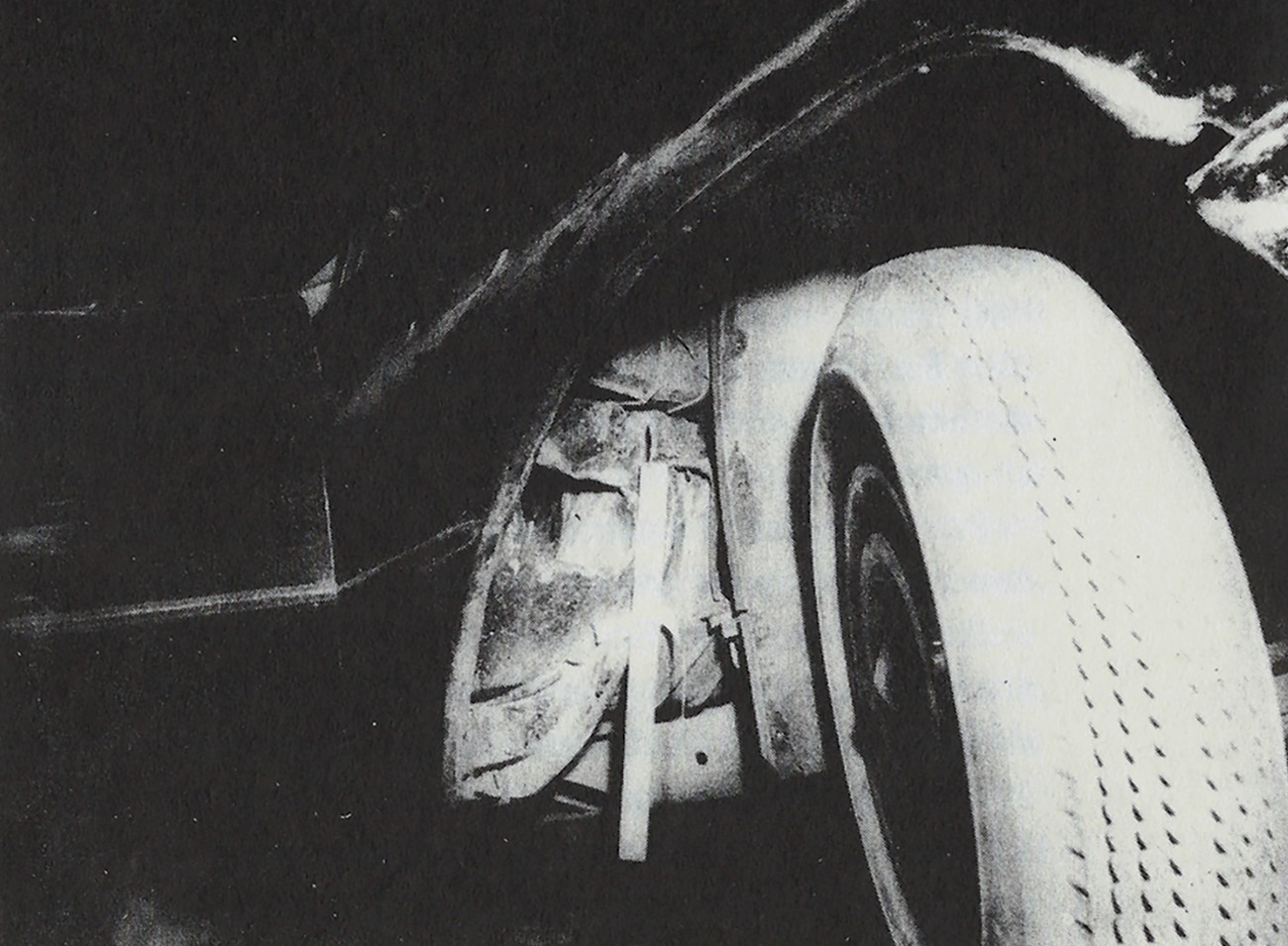

Tearing Apart the Car

This was one of the last locations that I researched for this film, getting a little assistance from Blakeslee. While not explicitly covered in any movie location websites, the rumor was that they filmed this car-disassembly scene at the same garage that was used for the real-life drug bust which was the basis of this movie.

After Blakeslee and I were able to find some I imagery of the NYPD Shop 1 Fleet Services Division in Maspeth, it seemed to match what appeared in the scene (although it was hard to tell for sure since you never get any clear views of the space).

In the movie, the car was a flamboyant 1970 Lincoln Continental Mark III, but the real drug car was a more modest 1960 Buick Invicta. Apparently, that model was popular with drug dealers back then, due to its many hiding places.

According to Robin Moor’s book, “The French Connection: A True Account of Cops, Narcotics, and International Conspiracy,” which was the source-material for this movie, “the 1960 Buick Invicta had a peculiarity in body construction conducive to the installation of…extraordinary, virtually detection-proof traps concealed within the fenders and undercarriage.”

Back in 1961, drugs were indeed found in the rocker panels, just as it was portrayed in the film, but there was also a stash hidden behind the right front wheel well, totaling 112 pounds of smack.

Keeping things as authentic as possible, Friedkin had the real mechanic, Irving Abrahams, play himself in movie as they recreated the actual event. In fact, many of people involved in the 1960-62 operation appear in the movie in small roles.

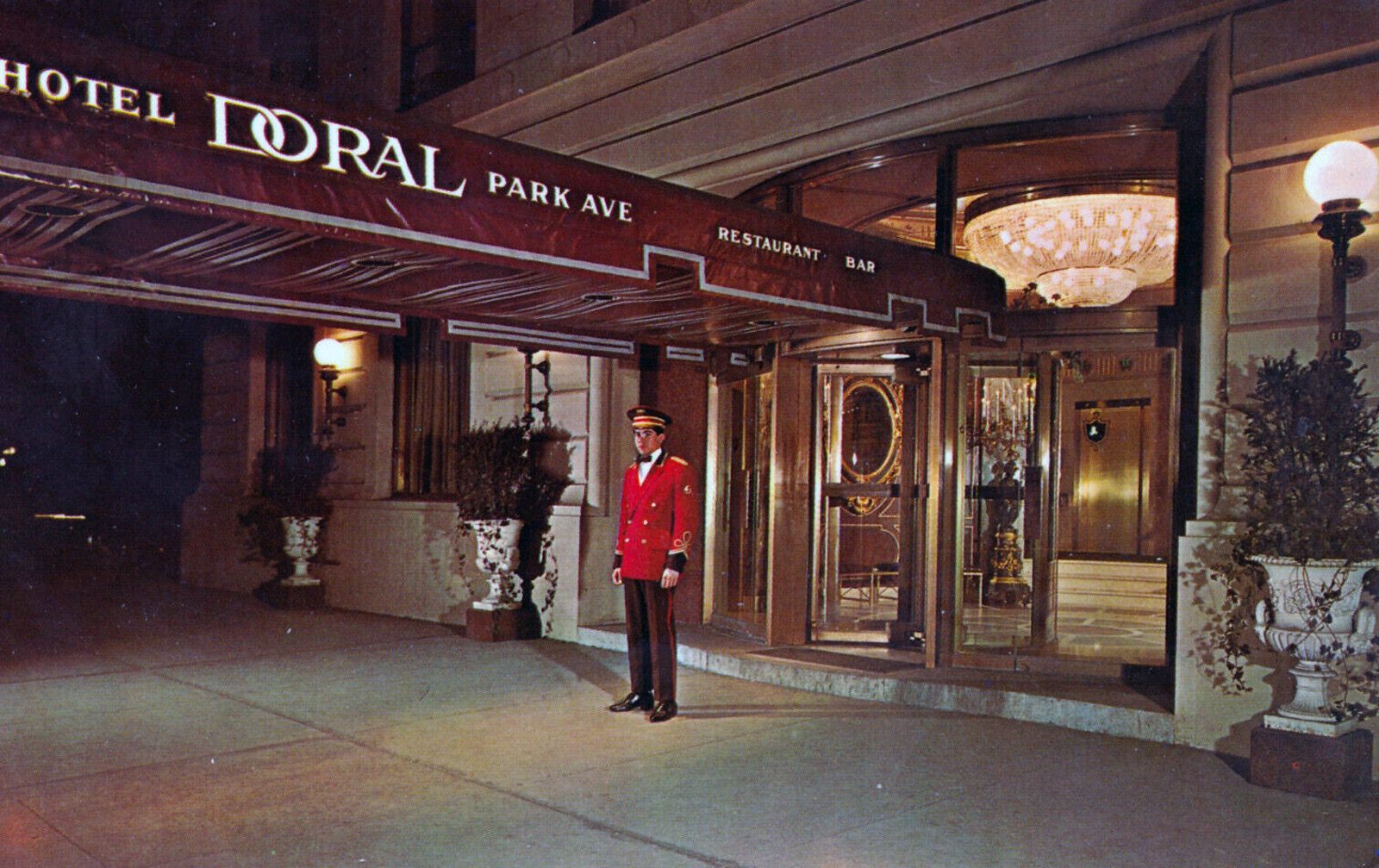

Devereaux Gets Nervous

This location wasn’t specifically identified in any sources that I could find. It’s implied that the hotel Devereaux stays at is near the parking garage on 38th and Park Avenue, and by what I could see out the doors, it appeared the hotel was indeed on Park.

Turns out it was all the same building, which I verified by matching the brick and windows across the street.

The hotel was called the Doral, operating at that location since the late 1940s. It was a popular destination for visitors of New York, known for offering weekend packages that included city tours and tickets to a Broadway show.

The Doral lasted until around 2004, when it was taken over and renamed 70 Park Avenue. At that point, the hotel received a major retrofit and as you can see in the above images, the lobby now looks very different from what appeared in The French Connection.

Considering its prime midtown location and luxury accommodations, I was surprised that 70 Park Avenue’s rates (in March of 2025) start at a reasonable $129 per night. A pretty big difference from the going rate at the nearby Fifth Avenue Hotel, which start at around $995.

The Drug Deal Finally Goes Down

After one long, continuous chase, the movie finally ends at the southern end of Randalls island, which was still unofficially referred to as Wards Island. About ten years prior, there were still two separate pieces of land in this part of the East River — Randalls to the north and Wards to the south.

By the time this movie was being made, most of the landfill had been loaded into the water channel that separated the two land masses, called “Little Hell Gate,” and the conjoined island was officially designated Randalls.

The bridge that ran over the former waterway (where Frog One discovers the police blockade) remained in place for several years after that, lasting until the mid-1990s.

Even though Little Hell Gate has mostly been filled in, the Department of Parks & Recreation has developed part of it into a sort of nature preserve with forested areas, meadows, and a salt marsh surround by a series of pathways.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the island was home to hospitals, industrial facilities and a prison. Today, it’s mostly parkland, although the island still has several public facilities, including homeless shelters, a fire training academy, and a wastewater treatment plant.

The climatic (or anti-climatic, depending on your perspective) ending to the movie took place at an old hospital garage and an abandoned bakery. The hospital was razed in the 1950s and the ruins seen in the movie were fenced off from the nearby athletic fields.

In 1971, the area had become quite rundown and used as a dumping ground by locals. This continued into the 1980s, causing garbage and debris to pile over the service road that was used by the characters in the film.

However, the old bakery (described in the script as a crematorium) was still standing when Dr. Speet took his French Connection inspired photographs in 1986.

Things were a little more dilapidated, but more or less unchanged after 15 years.

Dr. Speet even discovered the same overturned chair that can be seen briefly in one panning shot.

The only things missing were the sheets of tracing paper that were placed on the windows by the movie’s cinematography department. They did it to create a more diffused lighting pattern, and as an added bonus, the paper helped hide the fact there was major snowstorm raging outside on the day they were filming.

And with that, our long chase through these French Connection filming locations comes to an end.

While not my all-time favorite performance by Hackman —that’s reserved for his work in 1974’s The Conversation— he still does a knock-out job as the morally-ambiguous detective, Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle. And I think he does an even better job with the role in the 1975 sequel, exploring the inner workings of a conflicted cop.

Just the same, I’m not sure I’ve ever seen Hackman give a bad performance in his long career, even if he’s in a bad movie. He’s one of those actors that’s always a joy to see on screen, even if he’s playing a despicable character.

But as I stated in my introduction to this post, the real star of The French Connection is New York City, enhanced by William Friedkin and Owen Roizman’s discerning ability to capture its gritty rawness, without emblematizing it as a worthless wasteland.

Naturally, when people think of The French Connection, their minds go to the epic car chase. It was one of three chases produced by Philip D’Antoni and executed by stuntman Bill Hickman in a period of five years. The first was in 1968’s Bullit, then in this film, followed by 1973’s The Seven-Ups. While it’s hard to chose a favorite, I categorize them as the following: Bullitt had the best setting (the San Francisco hills), French Connection was the most creative (pitting a car vs a train), but The Seven-Ups had the most superbly-executed stunts.

Having said that, I think another key to The French Connection‘s success is its unconventional story structure. The movie is essentially one long police tail that keeps escalating as time marches on. We learn everything we need to know about the main characters through their actions in this extended game of cat-and-mouse. By never hitting us over the head with “character development,” it only increases the raw, documentary-style experience.

At the time it was being made, The French Connection marked one of the most ambitious movie projects ever to be filmed in New York City, purportedly using eighty-six separate locations in four out of the five boroughs (not to mention Washington DC and parts of France). That on its own, was quite the achievement.

When French Connection was being made, there hadn’t been many feature films that depended so heavily upon photography for its dramatic impact, and it certainly paved the way for future urban thrillers, such as Death Wish, Serpico, and The Taking of Pelham One Two Three.

The gutsy visual style helped establish an authentic atmosphere; creating mood, building pace, and enhancing all of the actors’ performances, making it more than just a slam-bang action flick. While it obviously has some extremely excessive scenes, I always loved how the movie captured some of the mundaneness involved in good police work.

The film was a hit with both audiences and critics, ending up winning five Academy Awards — best picture, direction, screenplay, editing. and best lead actor.

The critical and commercial success of The French Connection not only catapulted Hackman into stardom, it helped boost the careers of Roy Scheider (who was relatively unknown at the time) and William Friedkin (who would next make the monumental horror classic, The Exorcist).

It’s sad to see Gene go, but thankfully, we have a treasure-trove of great movies like this to remind us on how amazing of an actor he was. All you gotta do is pick one.