Starting off as a low-budget vehicle for a young TV sitcom actor, Saturday Night Fever became an instant box office smash, catapulting John Travolta into superstardom. But what’s unusual about this 1977 hit is how it combined New Wave cinema with teenage-friendly pop — two seemingly incompatible genres — essentially creating a gritty, R-rated dance movie.

Taking place almost entirely in Bensonhurst and Bay Ridge, Saturday Night Fever tells the story of Tony, a 19-year-old Brooklynite who still lives with his extended Italian family as he works at the local hardware store by day and dances at the local disco by night. When he meets Stephanie, a beautiful dancer who is determined to break out of the dead-end Brooklyn cycle, he starts to question his own life choices.

Best of all, Saturday Night Fever was entirely filmed on location, offering a great look at two working-class neighborhoods in Brooklyn, which by many accounts, have remained unchanged since the 1970s.

Strutting

Since Saturday Night Fever is one of the most iconic American films from the 1970s, there were a lot of websites that explored its filming locations.

When it came to this opening sequence, most websites listed the address of Lenny’s Pizza, but didn’t indicate any other specific locations, including the clothing store where Tony puts a down payment on a shirt. Figuring almost everything was shot in the vicinity of the pizza place, I was determined to nail down the exact spot of each key moment from this sequence.

To help speed things along, I enlisted my research partner, Blakeslee, to lend a helping hand.

The first thing he found was the location of the opening shot of Tony’s strutting shoes, which was on 20th Avenue, just north of 86th Street. He also helped figure out where Tony is momentarily distracted by the first lady passerby.

Based on the El tracks that curved in the distance, I had already assumed it took place on the northside of 86th Street, but it was Blakeslee who got an exact address. He did it by figuring out that one of the store signs said, “Reflection 1,” which according to a 1975 edition of The New York Times was located at 1951 86th Street (although neither of us ever figured out what kind of store it was).

Blakeslee was also able to decipher the name of the adjacent store to be “Eebee’s,” which according to a 1970s newspaper ad I found, was located at 1953 86th Street.

As far as I can tell, Eebee’s was a chain of your typical discount clothing stores that were ubiquitous in NYC during this period. They were the kind of place that when you walked in, your nostrils would flare from the sharp synthetic odor coming from all the cheap imported garments.

The set-up was almost always the same: an open storefront with a listless security guard stationed there, a series of cash registers lined on a raised counter along the back wall, and decade-old inventory crammed on racks and bins, usually accompanied with hand-written signs advertising “limited-time” discounts (even though the signs were clearly permanent fixtures.)

While a lot of these types of stores are gone from New York today, to my surprise, on Kings Highway in the Midwood section of Brooklyn, an Eebee’s actually survived all the way until 2018.

After Tony gets some pizza slices and passes Reflection 1 again, the next shot is a close-up of him carrying the paint can. I figured out this location after spotting a phone number on a door in the background which I discovered was for a Basile Realty Group at 8520 20th Avenue. (It’s basically the same location used for the first close-up shot of Tony’s shoes).

Amazingly, up until 2021, the space was still home to the same real estate company with the exact same phone number. Even the storefront was practically the same, down to the faux-brick exterior. Unfortunately, the agency is now gone and the storefront is almost completely unrecognizable except for the side entrance (see the “before/after” image above).

When it came to the clothing shop where Tony puts a down payment on a blue shirt, it looked like it was situated on a corner. So, the first thing I did was check out the 1980s tax photos in the NYC municipal archives of all the corner lots in that area.

I quickly zeroed in on a tax photo of the northwest corner of 86th and 20th which showed a very promising store called, “Shirtown.” After studying the layout of the front entrance, I became convinced Shirtown was the store used in this sequence — especially since it was located right next door to Basile Realty Group.

As a side note, if you’re a fan of Martin Scorsese’s After Hours, you might recognize the shirt salesman to be Murray Moston, the same actor who played the token booth operator at the Spring Street Subway Station who refuses to give the main character, Paul, a free token.

The last part of this opening sequence where Tony tries to pick-up another lady passerby was pretty easy to nail down. This was thanks to the Benson Twin Theater at 2007-2009 86th Street which was prominently featured in a couple shots.

The Benson, a 1,500 seat theater named after the Brooklyn neighborhood it resided in, first opened in 1922 with the comedy/drama, School Days. On that opening night, it was reported that the crowd was so riotous (supposedly storming the theater doors in hopes of securing a seat) that police were called in to keep things in check.

Twenty years later, the theater was still a popular destination for local residents, including future media host, Larry King. In a 2007 interview with The LA Times, King recalled that after his father’s death, his family struggled financially, but his mother was able to procure a complete set of dishes from a weekly promotional event at the Benson where they’d give the attending ladies a free plate.

By the early 1970s, as the theatergoing market started changing, the Benson tried its hand as a porno house. Then, after the theater was split into two screens in 1975, it was renamed Benson Twins and they started showing mainstream movies on one screen and x-rated movies on the other (which I’m sure made for some interesting mingling at the concession stand). However, that didn’t last long and by the time Saturday Night Fever was being filmed, the theater switched back to showing just straight films.

During the next decade, the Benson Theatre was closed more than it was open, and in 1988 it finally closed its doors permanently, but the building itself is still around and currently houses a Rite-Aid drugstore. (You can see some of the theatre’s original ornamentation near the top of the building in the second-to-last “before/after” image above.)

To confirm the exact spot where Tony interacts with the lady, I found a 1980s tax photo of a clothing store at 2025 86th Street called S&J (short for Shirts & Jeans), which matched the film. The most noticeable matching element was a series of distinct red, white and blue panels at the store’s base.

By the time the 1980s tax pic was taken, you can see the store had some very Travolta-looking artwork painted above the entrance. I assume it was added to the the storefront in order to capitalize on Saturday Night Fever‘s popularity (even though Tony is never seen wearing jeans in the movie).

And with that, Blakeslee and I had identified the filming location of pretty much every moment from this remarkable opening sequence.

One thing that helps make this sequence so memorable is the upbeat music, and while most people associate Saturday Night Fever‘s soundtrack with the Bee Gees, apparently during the film’s production, the only Bee Gees’ song they had secured was a demo version of “Stayin’ Alive.”

According to director John Badham, the sound department played the song while filming this “strutting” sequence so John Travolta could step to the beat. And if you look closely, you can actually see some of the extras on the street also walking to the beat of the song.

When filming commenced in March of 1977, the first thing they shot was this opening “strutting” sequence. However, as the day progressed, the crew quickly discovered how big of a star Travolta already was when huge crowds gathered to watch the sexy TV personality in action.

Even though NYPD officers were on set to keep things somewhat in control, a large, boisterous mob can be a distraction to the actors and a nightmare for the sound department. So to allay the situation, the crew had to make some adjustments to the shooting schedule, forcing them to film mostly in the dead of night or early in the morning. Also, Badham claims they leaked fake call-sheets with incorrect information to help throw tenacious fans off the scent.

While those techniques helped reduce the number of onlookers during production, a large crowd was encouraged to gather along 86th Street in 2018 when Travolta returned to Lenny’s Pizza with his wife Kelly Preston to promote their new movie, Gotti, and enjoy a couple slices.

Donning a black shirt and white jacket that mimicked the famous outfit he wore in Fever, a visibly humbled Travolta told reporters, “I never expected this big a turnout, it was awesome.” (Sadly, the number of people who attended this event was probably greater than the number of people who went to see Gotti.)

Unfortunately, just as I began writing this post, the owners of Lenny’s announced that after 70 years of business, they would be closing the shop. 77-year-old Frank Giordano, who bought the pizzeria shortly after it was featured in this film, said the closing had nothing to do with finances but he simply decided it was time to retire.

Lenny’s officially closed its doors at 10pm on February 19th after a full day of serving block-long lines of loyal customers wanting to grab one last slice. Even though I didn’t get to go there on their last day, I was able to experience Lenny’s pizza when I went there to take the modern pictures a couple years ago. I even stacked two slices on top of each other, but did it with one Sicilian and one regular… which garnered a few odd stares.

2024 UPDATE: I always had a faint hope that Lenny’s would be taken over by a local restauranteur who would continue to serve pizza in the space.

But it looks like it will instead be Bonchon Chicken, the international Korean fried chicken restaurant franchise.

Hardware Store

This hardware store was already identified on several websites by the time I started researching this film, but I did make sure to check out the address in Google Street View to verify it. While the storefront has changed quite a bit over the years, the buildings across the street are more or less the same, making it easy for me to confirm the location.

While it’s hard to tell from the image above, when I took the modern pictures of the location in 2018, it was actually still a local hardware store. But inside, not much remained from the 1977 movie, except for the backdoor where Tony snuck in with the paint can.

The hardware store closed down in 2019 and the space has since become a social service center called “Family Need.”

The Manero Home

Aside from the dance club, the family home is the most widely published filming location from Saturday Night Fever.

When I checked out the location, I was surprised to discover that the Manero home was pretty much the only house on the block that got a dramatic renovation to its exterior, rendering it almost unrecognizable from the film. Strangely enough, one of the owners who did the remodeling originally bought the house because he was a big fan of Fever.

The two owners also did some renovations to the interior, but kept several period details on the first floor. The most noteworthy holdout is the dining room, where the framework molding and built-in china cabinets look almost exactly as they did in 1977 when Tony told his slap-happy father to “watch the hair!”

In addition to the dining area, Tony’s bedroom, the bay windows near the front entrance and the staircase have been preserved as nearly picture-perfect matches.

In 2017, about twelve years after buying the house, the owners decided to put the property on the market, with an asking price of $2.5 million. Three years later, it ended up being sold at a reduced cost of $1.8 million, which is still a pretty hefty price tag and something a working-class family like the Maneros would no longer be able to afford.

Getting Picked Up

This is one of those locations that wasn’t of high interest with Fever fans, most likely because there’s not very much that happens in the scene other than Tony’s friends picking him up. However, The Movie District website ended up listing the address, which I confirmed was correct by matching up the relatively unchanged building on the corner of 79th Street and 3rd Avenue (featured in the first “before/after” image above).

The gang’s car that’s featured in this and several other scenes was a 1964 Chevy Impala hardtop, which was personally picked out by director John Badham. He was subsequently told by a few locals that someone from Bensonhurst would never be caught dead driving a Chevy and would more likely drive an old Cadillac. But production had already spent a good chunk of money on two Impalas and getting them distressed, so they were stuck with they got.

Disco Club

As one might expect, 2001 Odyssey (inexplicably spelled with two Ds on their sign) has been, by far, the most sought-after filming location from Saturday Night Fever. The discotheque’s address has been documented on countless websites, books and magazines, making it a popular destination for fans of the film ever since its release. Even back in the 1970s, when Brooklyn was a much sketchier borough than it is today, throngs of tourists (mostly from Europe) would take the pilgrimage to 2001 to take a few steps on the famous light-up dance floor where Travolta shook his booty.

But before becoming a part of cinema history, the 2001 discotheque was a sparse, run-of-the-mill club in a mostly working-class neighborhood. While the clubs in Manhattan were all about money, fame and status, 2001 was more about the basics — getting drunk and getting laid. And when it was decided that Fever would film there, the art department knew they needed to spruce up the space, so they strung christmas lights everywhere and lined the walls with aluminum foil to give it a textured metallic sheen. But the biggest (and most expensive) improvement was the lighted, flashing Plexiglas floor which cost production around $15,000.

While Saturday Night Fever helped make 2001 Odyssey a popular destination for a few years, when disco music started losing its luster in the early 1980s (led by an aggressive “disco sucks” movement), business started to wain. In 1987, owner Jay Rizzo decided to change the name to Spectrum and turn the place into a gay club, but the change didn’t do very much to boost profits, and the club was permanently closed in 1995.

When it came time to sell off the club’s inventory in 2005, a strange custody battle ensued over the famous lighted disco floor. It started when the nearly 30-year-old item came up for auction and the club’s former bouncer, Vito Bruno, was the first and only person to bid on it, which resulted in a rather unusual exchange with the auctioneer.

According to Bruno’s lawyer, it went down like this:

When they put the dance floor up, Mr. Bruno bid a thousand dollars. And the auctioneer said, ‘I have a thousand, can I hear two?’

So, Vito looks around, and doesn’t see anybody bidding. He says, ‘Okay, I’ll give you two thousand.’

‘I have two, do I hear three?’

And he still looks around. He goes, ‘Okay, I’ll give you the three, but who am I bidding against?’

‘Okay, I have three, do I have four?’

‘Look, I’ll give you the $4,000, but there’s nobody else bidding.’ And he did that until he bid six, and then the auctioneer said the item was withdrawn.

Afterwards, club owner Jay Rizzo told Bruno that he had no intention of letting the floor go for such a meager sum and had a Beverly Hills company re-auction the item, which netted a final bid of $160,000. But of course, Bruno’s position was that it was no longer Rizzo’s to sell.

That led to a bitter court battle in the Kings County Supreme Court the following year. In the end, the judge ruled in Bruno’s favor, awarding him solo ownership of the floor. Once these legal matters were over, Bruno held onto the 24×16 foot piece of movie memorabilia for about ten years, until he finally decided to auction it off himself. Sold by the California auction house, Profiles in History, the floor ended up going to an anonymous buyer for $1.2 million. (A tidy little profit.)

That led to a bitter court battle in the Kings County Supreme Court the following year. In the end, the judge ruled in Bruno’s favor, awarding him solo ownership of the floor. Once these legal matters were over, Bruno held onto the 24×16 foot piece of movie memorabilia for about ten years, until he finally decided to auction it off himself. Sold by the California auction house, Profiles in History, the floor ended up going to an anonymous buyer for $1.2 million. (A tidy little profit.)

It’s still unknown as to who that buyer was, but some have speculated that it was Mister Tony Mareno himself, John Travolta. I don’t know if that’s true, but it’d be a wonderful ending to this story if it is.

But back when the fate of the iconic floor was still being argued in court, the old club on 64th Street was being demolished and replaced with a bulky, nondescript commercial building. The majority of the new building was made up of conventional office space, but one of its tenants, a Chinese restaurant called Bamboo Garden, would later play a small part in honoring Saturday Night Fever.

In December of 2017, to celebrate the movie’s 40th anniversary, Bamboo Garden allowed Italian businessmen and TV personality Gianluca Mech to convert their restaurant into a recreation of the old discotheque. To pull off the transformation, it reportedly cost Mech over $200,000 — none of which went towards aluminum foil.

The polyester-infused bash brought in lots of long-time local residents, as well as guitarist Ed Cermanski of the Trammps, who performed his band’s hit, “Disco Inferno.”

Also in attendance was actress Karen Lynn Gorney, who played Tony’s love-interest in the film, and 79-year-old DJ Monti Rock, who spun records at the original 2001 Odyssey Club and played himself in the film.

Even though the club’s address has been widely published for a long while, I personally wanted to also figure out where exactly the boys parked their car before going into 2001, which hadn’t been previously identified.

It seemed plausible that the car was parked on the same block as the disco. However, since a lot of the buildings in the area had been replaced or remodeled since 1977, I had to do a little digging to figure out the exact parking spot.

With the help of 1980s tax photos of the area, I eventually figured out that they parked the car at 816 64th Street, only a couple hundred feet from the club entrance. And even though the buildings they parked in front of got replaced around 1985, the residential apartment building with the tall front staircase which they walk past is still standing today and mostly unchanged.

Playing Basketball

When I began researching this film a few years back, as far as I could tell, the only website that had any info on this basketball court was the Movie District. Since then, numerous sites have also listed this filming location, but I’m not sure if they did original research or just picked it up from another site. Regardless, I’m sure it would’ve been pretty easy to figure out since there are only so many parks in that part of Brooklyn, and the nearby elevated highways would almost certainly lead any researcher to John J. Carty Park which sits in the shadow the Gowanus Expressway.

Even though I didn’t have to do any detective work to find the location, I did have to do a little stumbling around when I went there in person, trying to figure out the exact spots used in and around the park. While the lampposts and basketball hoops have been moved around a bit since the 1970s, the support posts for the elevated highway were unaltered and provided a good guide to help me get my bearings.

And as a nice little bonus, when I was taking modern photos of the location, I discovered a pristine, 1974 tan Volkswagen Beetle parked on the street next to the park, looking as if it was transported straight out of this film. (See the last “before/after” image above.)

Car Lot

This was one of only a few filming locations that wasn’t identified on any websites. In fact, none of them even seemed to show an interest in identifying it.

Since this scene took place directly after the basketball scene at John J. Carty Park, I hoped that maybe it would be located in the same general vicinity. Fortunately, it ended up taking place only a couple blocks away, although it was a little tricky to spot at first since a large apartment building now stands where the car lot used to be.

However, the homes across the street from the old car lot are still around today and looking pretty much like they did in 1977, making a confirmation of this location fairly straightforward.

Dance Studio

Like most locations from this film, the address of Phillips Dance Studio has been identified on numerous websites, so there wasn’t much research needed on my part.

In the time since this movie was made, this section of Brooklyn has seen a lot of cultural changes. What used to be primarily an Italian, Irish and German neighborhood is now home to a large enclave of Chinese immigrants. In fact, Bensonhurst currently has more residents born in China and Hong Kong than any other neighborhood in NYC and is often referred to as Brooklyn’s Chinatown.

But the area is still home to a large Italian-American population and continues to have a working-class vibe that is a far cry from the sleek Manhattan lifestyle across the river.

Running Into Gus

Not much research was needed in figuring out the location of this quick scene since it starts at the same place where Tony gets picked up by his friends earlier in the movie. And with several building numbers clearly visible in the background during this single tracking shot, it was easy to figure out exactly where the scene ends.

Like several other locations in Bay Ridge, it was nice to see that all of the buildings have survived into the 21st century and that a few of the businesses have also survived, including the dry cleaners at 7908 3rd Avenue.

Coffeeshop

This eatery was already identified on several websites when I started researching this film, so there wasn’t much work involved. Although with the Verrazzano Bridge featured prominently in the background, I don’t think finding this location would’ve been too difficult. While it appears to be a coffeeshop in the movie, the place was actually a popular seafood restaurant called Fisherman’s Corner.

There wasn’t much information about the walking scene that takes place after Tony and Stephanie leave the diner, but since it was shot on the same block, it was easy to match up the buildings they pass. The easiest thing to match was Kelly’s Tavern which is not only still in business, but has the same facade and signage from 1977.

When I went to this location in person to take some modern pictures, the one place I wasn’t so confident I’d be able to get a picture of was the inside the diner, which had since become a car leasing service called Signature Auto Group.

In general, getting photos of any interior can be a little tricky — it all depends on what kind of place it is. Most of the time, bars, restaurants and small independent shops are fine with picture-taking (and sometimes even overjoyed that their place is a part of movie history), but a lot of other places are not so hospitable. So whenever I think I might get a little resistance, I have adopted a sort of silly tactic, but one that has proven to be effective — I put on a fake British accent.

I’m not sure if there’s something comforting about a British accent, but I figure it’s a bit more disarming if managers think they’re being approached by a visiting foreigner, opposed to some obtuse local. I used this tactic when I went to take pictures of an upscale steakhouse for the 1988 film, Big, and the manager was extremely accommodating, giving me exclusive access to the restaurant during non-business hours.

However, in 2018, when I went to this Fever location, it was before I learned the British accent trick, so I went into this auto leasing office with my charmless New York essence on full display. Once inside, I approached one of the agents at his desk and asked if I could take a couple quick pictures for a movie project I was working on. He told me I’d have to ask the manager to get official permission, but that the manager was “not available.”

Then, with a typical “I don’t give a shit” Brooklyn attitude, he immediately turned his back to me. But I quickly assessed that he did that not to be rude, but to give me the opportunity to take a couple quick snapshots on the sly. Thirty seconds later, he turned back and gave me a “done with your stupid whatevah?” look, followed by a “now get the hell outta here” hand wave.

After Rehearsal

This is another one of the few locations that wasn’t already identified on any movie websites, but definitely seemed findable.

As the two characters stroll down the street, several different stores are clearly visible in the background. The two most obvious ones were an Optimo Cigar Shop and a bar called Reda’s Corner that appeared behind the characters at the top of the scene (see first “before/after” image above). I knew that Optimo had a plethora of locations throughout the city in the 1970s, so I thought narrowing it down might be too much work. But Reda’s looked like a unique establishment that would only have one location, so that seemed like a good place to start.

There wasn’t much information on Reda’s out there, but I did find a collection of non-fiction stories and articles by New York Daily News journalist, Jimmy Breslin, that mentioned the tavern. While it didn’t give an exact address, it did describe it being near the intersection of 86th and 4th Avenue, and after checking out that intersection in Google Street View, I determined the tavern used to be on the southwest corner at 8602 4th Ave. That meant the scene started on the southeast corner and proceeded along the south side of 86th, ending at 5th Ave.

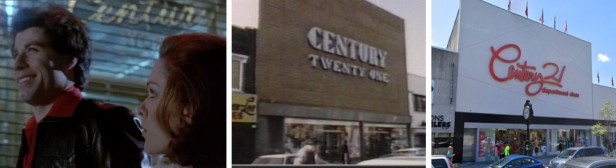

After figuring out where this scene started, I found a couple other clues that helped track the exact walking route the couple took. The most noticeable clue was a window they pass that said, “Century” on it. Since the window was part of what looked like a large department store, I surmised that it was a Century 21 — a chain of department stores operating primarily in the northeast. Turns out I was correct, and in fact, there was still a Century 21 at that location up until December, 2020.

But in what seems to be a recurring theme in this post, Century 21 was forced close after the Gindi family (who owns the chain of 13 stores) filed for bankruptcy. While this part of 86th Street is still a fairly active shopping hub, Century 21 was the flagship retail center, and now with it gone, the business community is trying to lay out a new plan. And that plan seems to include destroying the now-vacant 170,000-square-foot retail buildings owned by the Gindis and replacing it with something larger.

WIth Century 21 now closed, pretty much all the stores that appeared in this scene are now gone.

One of those stores was a Thom McAn Shoes, which appeared near the end of the scene. Thanks to the 1980s tax records, I figured out that it used to be located at 474 86th Street, which helped confirm that when Stephanie crosses the street at the end, they were on the southwest corner of 5th Avenue.

Playing on the Bridge

Not much to say about this scene, since it’s obvious it took place on the Verrazzano Bridge (officially known as the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, but no one I know calls it that). I’m pretty sure they dance along the eastern tower on the Brooklyn side, but it’s hard to tell for sure.

But if you want to see the bridge up-close and you don’t have a New York E-ZPass, it’s going to cost you. What started off at 50¢ when the bridge first opened in 1964, the toll has gone up to $10.17 in 2021, making a round-trip cost over 20 bucks. (And if you try to park the car on the bridge like the characters do in this scene, the traffic violations could easily grow into the hundreds.)

Tony’s Brother

While I was disappointed that the Manero house had gone through major renovations, making it practically unrecognizable from the film, I was relieved that pretty much all the other houses on the block were unchanged. Also, I was happy to see that the large Sycamore tree in front of 221 79th Street is still standing — and since the species can live up to 250 years, there’s a chance it’ll be standing there for a while.

White Castle

When I started doing in-depth research on this film in 2016, an address of 9201 4th Avenue for this White Castle kept popping up. However, since there’s no White Castle on that corner anymore,I had a little trouble confirming it at first. Back then, the NYC tax photos were not readily available online, so my only source was a 1977 Brooklyn phone directory at the NY Public Library.

While there was a White Castle at 9201 4th Avenue, I wasn’t sure if it was the same one from the film, since the hamburger franchise had many locations in New York City. But then I noticed in the scene that you could see a Kentucky Fried Chicken down the street. And sure enough, there still is a KFC on the corner one block east from the old White Castle.

A few years later, when the NYC Municipal Archives released the digitized tax photos online, I was able to find pictures of both the old White Castle and the old Kentucky Fried Chicken building, reinforcing that I found the right location.

Borrowing Bobby C’s Car

This location was easy to figure out since it starts at the already-established hardware store at 7305 5th Avenue then just travels south to the northeast corner of 5th and 74th Street. While the buildings on 5th have been modernized a bit over the years, the residential buildings on 74th are pretty much the same with a lot of the same trees still around.

Helping Stephanie Move

When I began looking into this scene back in 2016, no one had identified it. In fact, the Movie District website listed it as a “missing location,” and I was ready to take on the challenge.

The one advantage in searching for Fever filming locations is that almost everything was shot in a relatively small section of Brooklyn, which narrowed down the possibilities. And to further help things out, I discovered what looked like a 242 on the front door. So I just checked every house numbered 242 on every residential street in Bay Ridge starting at 100th and moving my way north. When I hit 93rd Street, even though the siding on the house had been updated, I could tell that I found a match.

All in all. it was a pretty quick search.

Manhattan Apartment

This apartment location is currently listed on a few different websites, but like the previous scene, it was still missing when I first started researching this film. By the looks of the brownstones, I could tell the apartment was somewhere on the Upper West Side in Manhattan, so I started cruising up and down a bunch of streets on Google Street View in search of a match. Then suddenly, I remembered that I had a copy of the film with audio commentary by the director, which I hoped might be of some help.

So, I went to this scene on the disc and to my delight, he actually commented on the location, saying he thought it was shot on West 76th Street near the park. So, I went to Google Street View, traveled down 76th, and soon zeroed in on number 34 which looked like a match (albeit a little brighter and less rundown). But since a lot of these brownstones look very similar to each other, I confirmed I got the right place by checking out all the neighboring buildings and made sure they all matched up, too.

Of course, the bridge they drive over was easy to identify. Each bridge that connects to Manhattan Island is pretty unique and it’s hard to mistake one for the other.

Sitting by the Bridge

This is yet another scene that had already been identified prior to my research. The only part I had to work on was trying to figure out where exactly the bench they sat on was located. Because the benches seen in the film have since been replaced, I used the trees and the perspective of the bridge to help me figure out where they sat. But since the new bench might not had been installed at the exact same spot as the old one, my “before/after” image might be slightly off.

I wonder if anyone in the Parks Department knew the history of that bench when they were in charge of removing it. It would have been cool if they kept that one bench intact and added a little plaque commemorating the film.

Fighting the Barracudas

Fortunately the location of the Barracudas Club was already identified on the Movie District website. It’s a good thing because it might have been a little difficult to find since it turns out it was the one Brooklyn location that wasn’t in either Bay Ridge or Bensonhurst. This scene was shot in Borough Park, which is an Orthodox Jewish neighborhood that’s just to the north.

While the neighborhood appeared relatively safe and peaceful during filming, assistant director Allan Wertheim warned the crew that the community could get very confrontational if they didn’t like what they were doing. Wertheim mentioned that when he worked on the Robert Redford film, The Hot Rock, several Hasidic Jews turned one of the picture cars over when they thought production had overstayed their welcome. I think that’s an impulse a lot of New Yorkers feel when they encounter a massive traffic jam caused by some big film production.

Bobby C Dies

This scene definitely freaked me out when I saw it as a kid, and still gives me chills when I watch it today. Apparently, when it came to filming this scene of Bobby falling off the Verrazzano Bridge, there was actually some real danger involved.

As I mentioned earlier in this post, in order to reduce the number of onlookers, production scheduled most of the exterior shoots late night/early morning. And since they were filming in early March, it got extremely cold at night and the bridge would ice up. So for the actors’ safety, director John Badham blocked the scene so Tony and Double J would crawl along the beam as they try to talk down Bobby C.

But apparently, Travolta didn’t want to do that. He thought it was important for the character to be standing up, and Badham reluctantly acquiesced. So that’s why in the scene, Tony is upright, while Double J is on his hands and knees. Fortunately no one was harmed in the making of this scene.

What’s interesting is that when Paramount Pictures released a PG-rated version of Saturday Night Fever in 1979, they had to make extensive cuts, but curiously, this horrific death scene was untouched. Most of the changes for the new version involved editing out the incessant profanity, as well as cutting out any nudity and minimizing the rape scene. However, when it came to violent imagery, there was very little altered.

The reason a PG version was released into theaters is because the studio wanted to capitalize on the wildly successful, more kid-friendly Travolta film, Grease, hoping to bring in more ticket sales from that younger market. Even though they did manage to add nearly nine million dollars more to their grosses, it was clear they were presenting an inferior product.

Barry Diller, chairman of Paramount at the time, was surprisingly frank when he discussed this tamer cut of the film to the New York Times. “Is it as good a film? I doubt it, but, at the same time, I don’t think people who go to see the PG version will be cheated. They’ll see the same story, hear the same music, see John Travolta.”

While the idea of watching the PG version of Saturday Night Fever today seems a bit pointless, the one fascinating aspect is its inclusion of several alternate takes where all of the offensive words were purged. These alternate takes were originally made to cover for television, and because the actors knew what they were doing wasn’t going to be in the theatrical release, they were more relaxed, which sometimes resulted in a stronger performance.

The fact so much work was put into making an alternate version of Fever just so kids could go see it demonstrates how important a theatrical release was to the film industry back then.

Riding the Subway

I couldn’t find much online about the specific filming locations for this subway montage, other than a few comments by subway snobs expressing their ire for the movie’s mixed up geography, pointing out that the different stations Tony visited didn’t make logical sense.

While I normally hate when a movie screws up NYC geography, it doesn’t really bother me in this case, mainly because Tony, who has just reached a dramatic crossroad, is in an almost zombie-like state, absently wandering the subterranean labyrinth. He doesn’t seem to have a real objective when he first enters the subway system, so it’s quite conceivable he would be going in different directions and blindly getting off at some random station without any specific purpose.

As to the actual locations used in this montage, even though there’s no signage visible, I’m pretty sure the first shot was filmed at the 53rd Street Station, which is also where Tony ends up a couple shots later, but just on the other side. What’s interesting is that the platform on the downtown side has round wooden columns, while the platform on the uptown side has squared metal columns, which is a convenient for a film crew to make it look like two different stations, or even two different subway lines.

Aside from the shape of the columns, not much at the 53rd Street station today looks like it did in 1977, especially after it was upgraded in 2017 as part of the MTA’s $72 million renovation project. You can tell things had been modernized even before you go underground by the looks of the black, futuristic subway entrances along 4th Avenue.

Incidentally, the type of subway car Tony rode on was the R30 model, built by St. Louis Car Company from 1961 to 1962. And if you want to sit on the same type of car used in the film, there’s one on display at the Transit Museum in Brooklyn,

Back in Manhattan

What’s interesting about Saturday Night Fever, which many would call the quintessential Brooklyn movie, is that it ends at this Manhattan location, with a hopeful and reformed Tony essentially choosing to leave his Bay Ridge life behind. From that, the movie’s message could reasonably be interpreted as being, “Manhattan is better than Brooklyn.”

While the people involved in Saturday Night Fever clearly had an affection for the eastern borough, Brooklyn is definitely characterized as being crude, coarse and lower-class.

This is a perspective that seems to had been strongly held by Travolta, who insisted that the sequel, Staying Alive, which took place almost entirely in Manhattan, be extremely positive and uplifting. Directed by Rocky-star Sylvester Stallone, Staying Alive is quite possibly the worst sequel ever made, not only because it’s so bad, but because the original was so good. The two films feel like they’re taking place in two completely different worlds. It’s like if the sequel to The Godfather was the movie, Superman III.

When I saw Fever as a kid, I obviously enjoyed it for the dancing, the nudity, and the non-stop swearing, but I could also instinctively tell that the characters were something unique. Later on in life, I realized that these characters were something that hadn’t previously been represented in cinema — certainly not in such a bold, unabashed way. These are not likable people, and the movie doesn’t shy away from that. But the secret to its success was casting John Travolta in the lead role, where his inherent sweetness comes through in his performance and makes you want the Tony character to succeed, even though he’s extremely flawed.

Of course, when it comes to Travolta, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention his dancing in this film. While not perfect, it’s nonetheless impressive, with several dance moves that look nearly impossible to execute. But the fact that his dancing is skilled but not professional, helps add to the reality. Also, by having a good portion of the dance sequences in wide master shots, it keeps things from looking too polished and almost makes us feel like we’re watching a documentary.

For me, Saturday Night Fever is one of those perfect NYC films. Not only does it have a ton of vintage on-location footage of the city, but it’s got interesting characters, great performances, incredible music, and an engaging story. In short, I don’t think there’s a single boring scene in the entire lot. It may not be my favorite NYC film, but it’s up there.

One person who did declare Saturday Night Fever to be their favorite movie of all time was film critic Gene Siskel. In 1978, he proved his fandom by buying one of the white suits worn by Travolta at an auction for $2,000 (purportedly out-bidding Jane Fonda by a hundred bucks). And just like what Vito Bruno did with the club’s lighted dance floor, Siskel later re-auctioned the garment for a tidy profit, selling it at Christie’s for $145,500. (Strangely enough, all these fans who bought items connected with the movie would later sell them off for a profit.)

While Saturday Night Fever is definitely a quintessential part of 1970s culture, it sadly isn’t a film that’s being viewed by new generations, probably due to some of its darker themes. But all that being said, that depiction of Travolta striking a dance pose in his all-white suit is probably one of the most iconic images in cinematic history.

Just goes to show what a pop-cultural juggernaut this film once was.

Fantastic research!

LikeLiked by 1 person

i enjoy all your posts. recently we caught the very end of The World, The Flesh and The Devil on tv and out of curiosity borrowed the dvd from the library. have you ever considered doing an installment on that film (admittedly, not a very good movie)? thanks a lot and best wishes,

Carleton Hoffman,

San Francisco

LikeLike

Thanks for your comments Carleton.

Yes, I’ve done some extensive research on “The World, The Flesh and The Devil,” and managed to track down all the locations used. While I agree it’s not a great film, there are definitely some compelling moments in there and it’s an interesting take on the post-apocalyptic genre. I do hope to do post about it at some point.

If you go to the “Movies Shot in New York” page and click on the movie poster, you can see the pics I’ve taken so far.

LikeLike

Very thorough article. Too bad that younger audiences don’t really appreciate what this movie was all about. They think it’s supposed to be a musical like Grease.

LikeLike

You did an excellent job researching the movie and recreating the scenes. Being born and raised in Brooklyn, this movie always brings me back to my childhood.

LikeLike

Hiya just come across this info on Saturday night fever must say i thoroughly enjoyed the history on the film n movie info and pics thanks again

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nicely done. Two comments: (1) The bar on 86th and 4th, next to the Optimo, is Reda’s, not Rena’s; (2) the dining establishment on 4th and 92nd was Fisherman’s Corner, a seafood restaurant, at that time. A diner, especially in NYC, was/is something completely different. I realize that in the scene they order just coffee/tea, but not a diner despite the diner-type order.

LikeLike

One more: the “lunch break” photo is at the Green Tea Room, 443 86th St, a Bay Ridge favorite of the past.

LikeLike

Thank you very much for your brilliant research. In 2019 while visiting NY from England I made the subway trip to Bay Ridge just to sit on that bench. One of the highlights of my trip.

LikeLike