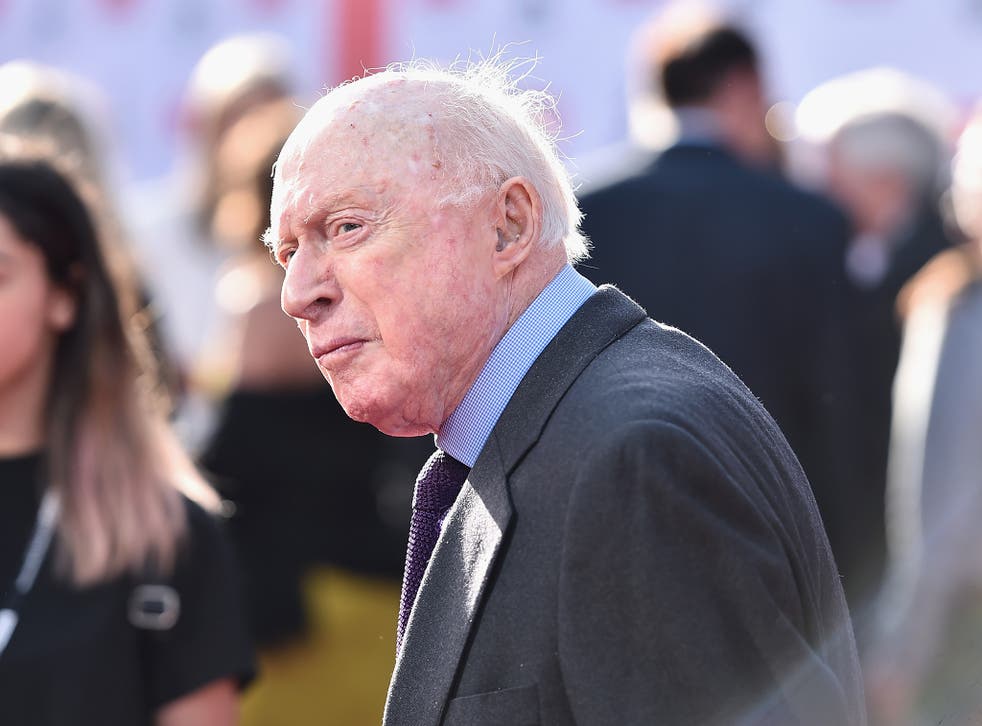

In May of this year, one of the last character actors from the golden age of Hollywood, Norman Lloyd, passed away at the ripe old age of 106. His nine-decade acting career began in the 1930s, getting work on the New York stage (including Orson Welles’ famed Mercury Theatre), but his very first feature film was this 1942 Alfred Hitchcock thriller, Saboteur, where he played the titular character.

After Saboteur was completed, Lloyd maintained a close working relationship with Hitchcock, eventually producing and directing on his anthology TV show, Alfred Hitchcock Presents. In the 1960s and 1970s, Lloyd continued to produce and direct for several television series while also working steadily as an actor. However, his biggest and most famous acting gig came in 1982 when he landed the role of Dr. Daniel Auschlander on the TV medical drama, St. Elsewhere. After that, he continued to work as an actor into the 21st century, with his last role being in Judd Apatow’s 2015 film, Trainwreck, which he did when he was 99 years old.

In Saboteur, Norman Lloyd is devilishly evil as the main antagonist — the perfect foil for the two leads, played by Robert Cummings and Priscilla Lane (who were reportedly not Hitch’s first choices). The film takes place at several different locations across America, with its climactic ending taking place in New York City. While most of the action was shot at Universal Studios in Hollywood, there was some on-location footage shot in New York City, helmed by John Fulton who was part of Universal’s special effects department. Even though this was just second unit footage to be used as quick establishing shots and background plates, Norman Lloyd joined Fulton in New York City, helping make the footage more integrated with all the studio work done in Los Angeles.

All in all, there aren’t a whole lot of New York filming locations in Saboteur, and normally I’m not too enthusiastic to investigate second unit footage, but by having one of the main cast members there in person, I decided it would be a worthwhile endeavor. (Besides, the locations were all fairly obvious, making the research process brief and painless.)

New York Skyline

By the looks of the ironwork in the foreground, it was clear that this establishing shot was filmed on the Brooklyn Bridge looking at the lower Manhattan skyline. And even though I’m pretty sure it’s authentic, there’s something a little bit strange about this establishing shot.

While it appears to be taking place at night, the bridge and the buildings are visible and well-defined, which is something that wouldn’t be possible with the cameras and lenses that were available in the early 1940s. A night shoot like this would normally result in a big black canvas with just a few flickering lights from the building windows. What I think happened was unit director John Fulton filmed this at the “magic hour“ —just as the sun was going down— which gave the appearance of nighttime but still had some available light to keep the skyline from disappearing into a sea of black. He also probably closed down the camera’s aperture so any sunlight would appear more like moonlight.

But there’s also something kind of cartoonish about this shot. I couldn’t put my finger on it at first, but then I came up with a theory. If Fulton really did shoot this just as the sun was setting, probably not a lot of New Yorkers had their lights on at that point, and if they did, the light probably wouldn’t have registered on film. So I think the effects department added fake lit windows to the image to better sell it as a nighttime scene.

Regardless, the thing I always enjoy about these skyline shots is lining up the skyscrapers and seeing how much taller Manhattan has gotten over the years and what buildings still stand out today.

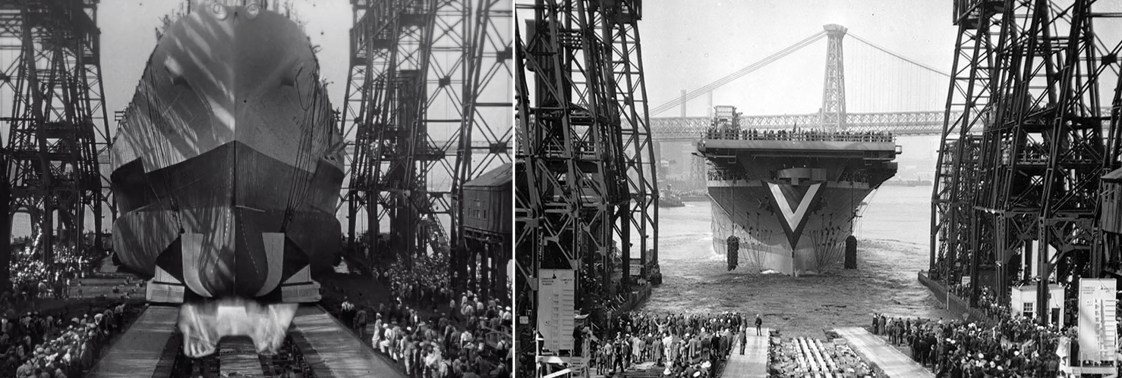

Navy Shipyards

I don’t think any original footage was filmed on location at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The one shot of the ship going into the water looks like it was old news footage of the Navy Yard that was reused for the film, with animation of an explosion layered on top of it.

Everything else looks like it was either a set or a similar-looking waterfront location in Los Angeles. One of the more elaborate sets was the one based on the Sands Street entrance to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. While not a perfect recreation, the pillars with the bird on top looked very close to what used to be at the entrance in the 1940s.

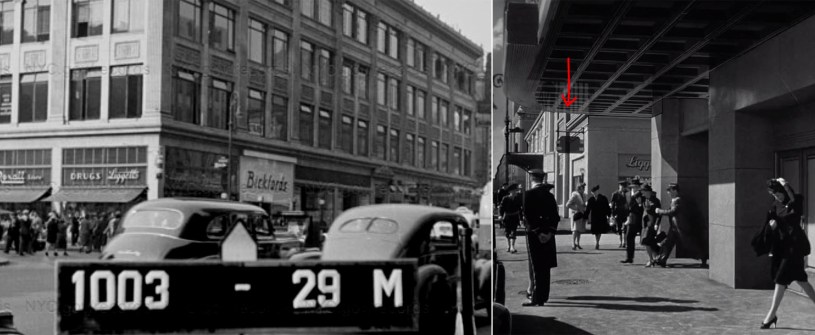

Rockefeller Plaza

This filming location, like pretty much everything else in this film, was easy to identify. The signage above the garage door entrance was the obvious clue. It did take me a little bit of time to figure out which building at Rockefeller Center Priscilla Lane was being held in but I eventually figured out the exact location and camera angle.

I believe at least one of the point-of-view shots looking out the window was filmed inside the actual building at 45 Rockefeller Plaza in NYC, but the shot of the cab drivers on the street was done back in Hollywood.

Movie Theater

While not necessarily obvious, it made sense that this movie theater sequence would be taking place at Radio City Music Hall considering it is adjacent to 45 Rockefeller Plaza. As far as I can tell, most of the sequence was shot in Los Angeles using recreations of the famous theater, but I do think they shot a few bits on location.

As indicated by the “before/after“ images above, I think the first interior shot of the theater and the last interior shot of the lobby were real, but everything else was fake, including all the action that took place outside.

Even though Norman Lloyd was on location in New York, since the outdoor scene needed Cummings and Lane to be in front of a fake Radio City exterior, I assume they had him at the fake exterior too so it would match. The music hall’s recreation was pretty well done and fooled me at first, but the stonework doesn’t quite match (the corners are more rounded at the real location) and the building across the street didn’t really look like what used to be there at the time.

I was impressed, though, that they put a Liggett’s Drug Store in the fake building across the street since that’s what was actually there in 1942. It was a nice attention to detail that not many people would notice, but it’s the kind of thing Hitchcock was known for doing.

Battery Park

Once again, this location was easy to identify, obviously taking place in Battery Park where the Liberty Island ferries depart from. Probably my favorite “NYC shot“ from this film is the one of the cab pulling up to the park with the extant buildings along Battery Place in the background. The one notable change is the now-inclusion of the Battery Tunnel Ventilation Building at 504 Battery Place (which can be seen in the center of the first “before/after” image above). The Ventilation Building would later be immortalized in cinematic history when it appeared as the fictional headquarters for the “Men in Black.”

It might be noted that prior to Fry’s arrival at Battery Park, there was one quick shot of him in a taxicab as he passes a capsized ship in the Hudson River. After he sees the damaged vessel, Fry smirks to himself, implying he and his conspiracy of saboteurs were responsible.

This was actual footage of the USS Lafayette (originally named SS Normandie), which burned and capsized on February 9th, 1942. It was temporarily rumored that it was the result of German sabotage, but it was later found to had simply been an unfortunate accident, where sparks from a welding torch ignited a stack of life vests and quickly spread to the ship’s varnished woodwork. Since the Lafayette was in the middle of being converted to a troopship for the US Navy, some of the vessel’s safety systems were deactivated, which proved to be a critical disadvantage to firefighters. The fire was eventually put out, but after being doused with over 6,000 tons of water, the ship started to list on its port side, eventually capsizing by the following morning.

Apparently the US government was not very happy with how Hitchcock interpolated these images of the former SS Normandie in his film and wanted him to remove the scene from the final cut. The director later commented, “the Navy raised hell with Universal about these shots because I implied that the Normandie had been sabotaged, which was a reflection on their lack of vigilance in guarding it.” It seems unclear whether this scene was removed from the film’s initial release, but it was definitely in place by the time it was reissued in 1948.

If you’re interested in seeing any artifacts that have survived from the SS Normandie, just go to Our Lady of Lebanon Maronite Catholic Cathedral in Brooklyn Heights. At its Remsen and Henry Street entrances, you’ll see a set of engraved bronze doors which were salvaged from the ship’s “imperial banquet room” and are decorated with large medallions depicting French scenes, including one of the ship itself

As to the location of this quick scene, there’s no question that the USS Lafayette was docked at Pier 88, which is at West 48th Street and 12th Avenue in Manhattan. However, some movie historians have postulated that the film was suggesting the unnamed capsized ship was at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Of course, I don’t think that’s the case.

Hitchcock was a stickler for detail and tried to make things as authentic as possible — and the Brooklyn Navy Yard simply wouldn’t make any sense. Since the preceding scene took place at Radio City Music Hall on W 50th Street and the following scene took place at Battery Park, the cab’s logical route would’ve been to go over to the West Side Elevated Highway (which ran above 12th Avenue at the time) and take it straight down to the park at the southern tip of Manhattan. And on that route, the cab could have easily passed Pier 88 along the way.

As further evidence that this was Hitchcock’s intention, if you look closely at the rear projection behind the cab, you can see it’s of an elevated highway.

I just love it when everything makes geographical sense.

Liberty Island

While there’s no question the climax to this movie took place at the Statue of Liberty, the only thing I had to figure out was what parts were shot at the real NYC location. As far as I can tell, most of the footage before they go into the statue was shot on location, while almost everything after that was done back in Hollywood using recreations of the statue’s crown and torch (the latter of which was built to scale).

Naturally, if a shot had the Statue of Liberty in it, I could use it as a guide to figure out where on the Island the action took place. This technique helped me quickly figure out where the ferry docked and which entrance the characters used to get inside the statue.

The only thing that took me a little time to nail down was the part where Pat goes to make a phone call. By the lighting and quality of the initial wide shot, I could tell that it was filmed on location in NYC (even though all the subsequent shots were done back at the studio), so the key was to study the base of the fort to see if I could find any matching stonework. And to better hone my search, I consulted a later wide shot taken from inside the crown which showed that the payphone area was fairly close to the ferry dock. With that in mind, I was eventually able to find stonework along the east side of the fort which matched what appeared in that initial shot.

Also, just to be safe, I double-checked the stonework that appeared around the entrance used by the two characters, just to make sure it was real and not a Hollywood recreation (which I briefly suspected when I first studied this scene). But I’m pretty sure it’s the real entrance — not only do the large blocks line up, but the tiny bumps and imperfections in the granite line up as well. Plus, the fact that a body double for Priscilla Lane was used for that shot makes me fairly confident that it was filmed in New York.

As I’ve already mentioned in this post, the only actor who was on location in New York was Norman Lloyd. Any New York footage that involved Robert Cummings’ or Priscilla Lane’s characters had body doubles take their places. This is patently obvious in this sequence on Liberty Island, where any parts that have Fry in them, Lloyd would invariable turn his head so we could tell it was really him, while any parts that have Pat in them, Lane’s double would deliberately keep her head pointed away from camera.

While the use of second unit footage has been a common practice since the dawn of movie-making, the idea of having one of the minor characters on location while they shot the material was a unique way to help out with the continuity. And from a financial standpoint, it probably didn’t affect the budget very much. After all, air travel and hotel accommodations for just one contract player wouldn’t cost the studio too much, especially if they were already going to be paying him his weekly wage regardless.

Surprisingly, this practice of implementing one low-level actor in its second-unit filming wasn’t used very often. The only other example I could find was from the 1950 film noir, Where the Sidewalk Ends, in which production brought character-actor Don Appell to New York so he could participate in the location shooting.

I’m sure there are other examples out there, but so far, every other film I’ve researched from this era used nothing but body doubles for their second-unit location filming.

Saboteur was Hitchcock’s first American movie to take place in America, and was one of only two pictures he made for Universal. While not perfect, it is an exciting film and moves along at almost a frenetic pace. In fact, one of the biggest complaints has been that there’s perhaps a little too much excitement in it, with so many action sequences and narrow escapes that it can become a little exhausting. But I’ve always said, even a flawed Hitchcock film is going to be better than most other films released at the same time period.

Saboteur was Hitchcock’s first American movie to take place in America, and was one of only two pictures he made for Universal. While not perfect, it is an exciting film and moves along at almost a frenetic pace. In fact, one of the biggest complaints has been that there’s perhaps a little too much excitement in it, with so many action sequences and narrow escapes that it can become a little exhausting. But I’ve always said, even a flawed Hitchcock film is going to be better than most other films released at the same time period.

Personally, I think the weakest part of the film is the lead actor, Robert Cummings. I always felt his performance was too glib — so much so, I never really cared if he succeeded or not. Interestingly, I found Norman Lloyd’s character to be the most enduring, even though he plays the villain. When he is hanging from the Statue of Liberty’s arm for dear life, I actually felt sorry for him, even though his character probably caused the death of countless innocent people. Just goes to show what a competent actor can do with a seemingly small and unsympathetic role.

It’s a shame Lloyd didn’t become as famous as some of his contemporaries — he certainly was talented, and in any interview I’ve seen of him, he appears intelligent, congenial and full of enthusiasm.

But perhaps personally, he received just the right amount of work in show business to keep him financially secure while relatively stress-free — the two best ingredients for a long, healthy life. In fact, Lloyd said that the secret to his illness-free life was “avoiding disagreeable people” — something that isn’t possible if you spend too much time in Hollywood. Of course, I’m sure having a supportive wife for nearly 75 years helped as well.

Marvelous work as always. Have you ever considered using a platform like YouTube, or does it interfere with your creative process? I’m not really a big fan of social media and the commercializing of everything, but you may reach a lot of people. Either way, thanks for your work.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Another fascinating post. Buster Keaton, of all people, used a similar stand-in technique during Our Hospitality. His friend Big Joe Roberts was very ill, so nearly all on-location shots used a double. The double would have his back to the camera, or be blocked by people passing in front. I never noticed this until someone pointed it out.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Wonderful work, Mark. I love that Lloyd worked with Charlie Chaplin as well.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yeah it’s incredible he worked with three masters of film — Welles, Hitchcock and Chaplin.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Funny, I always figured that ventilation building was prewar. Excellent post.

LikeLiked by 2 people