“Where the Sidewalk Ends” is a film that reunites director Otto Preminger with Dana Andrews and Gene Tierney, stars of his 1944 smash, “Laura.” Both titles are quintessential examples of film noir, rich with shadowy cinematography and dark, twisting storylines. But this time around, the moral compass of Dana Andrews’ character isn’t as patently obvious, offering us a more complex and ambivalent lead — one we’re not sure whether or not to root for.

Set in New York, “Sidewalk” presents a sordid metropolis full of crime and wretchedness, but also one that isn’t entirely bleak, where upstanding, honorable citizens are able to rise above the mire. The look of the film, like most noirs, was heavily influenced by German Expressionism, and cinematographer Joseph LaShelle creates a textured world of brooding mystery under the almost-constant shroud of night. At the same time, we’re offered an authentic depiction of the Big Apple, through an amazingly economic use of on-location shooting, coupled with realistic backlot sets.

By my count, production only filmed at five actual Manhattan locations (most likely executed by a small second-unit team), which amounts to just a little over a minute of total screen time. But in all respects, Preminger still manages to make “Sidewalk” feel very much like a credible New York story.

Police Station

Whenever I try to figure out the location of a police staton, I naturally start off by doing an online search of the precinct number. When it came to Manhattan’s 16th, I had a little difficulty finding much information on it, other than it didn’t seem to exist any more. That’s when I turned to the website policeny.com, which has helped me figure out police station locations in the past. Luckily, they had a short blurb on the old station house, with an exact address and a nice 1939 photo, confirming it was the same place from the film.

According to the site, after serving many years as the 22nd Precinct, the building at 345 W 47th Street served as the 18th Precinct from 1929 to 1940. Afterwards, it was a traffic station for a few years before becoming the 16th Precinct. Then, about a year after the 16th moved out in 1968, the building was demolished.

Today, there’s a small city park and playground on the site.

Besides being briefly featured in this film, the 47th Street station house had another notorious connection with the world of entertainment when Mae West was booked there on indecency charges after police raided one of her Broadway productions.

On October 1st 1928, as the curtain fell on opening night of the West-scribed play, “Pleasure Man,” over fifty people associated with the stage production were arrested in the Biltmore Theatre and carted away in paddy wagons to the nearby police station.

According to Meyer Berger’s 1983 book, The Eight Million – Journal of a New York Correspondent, the big desk room at the station house became cluttered with “fifty-five actresses and mincing male players” who were being booked for “participating in an indecent performance.”

A New York Times article published the following day indicated that West was informed by police that her play was likely to be raided, and after completing a performance for another Broadway production she wrote entitled, “Diamond Lil,” she went to the 47th Street police station to face the charges. She was booked and released on bail within a few hours, and immediately went to work to raise the money needed to get the other members of the company out on bail.

Two years after the Biltmore Theatre raid, twenty-four company members of “Pleasure Man” were put on trial for putting on a show that was “to the great offence of public decency,” with particular attention paid to an act involving a drag queen. However, after 14 days of testimony, the jury failed to reach a decision and the indictments were eventually dismissed.

During the whole process, Mae West seemed to take everything with stride, having already experienced a similar ordeal a few years prior.

During the whole process, Mae West seemed to take everything with stride, having already experienced a similar ordeal a few years prior.

It started in April of 1927, when West was arrested for giving an obscene performance in the first play she wrote, aptly titled, “Sex.” But her court hearing was less successful this first time around, and she ended up being fined $500 and sentenced to ten days in jail.

The first day of that sentence was spent at the Jefferson Market Women’s Prison in the West Village, and the remaining days on Welfare Island (now known as Roosevelt Island). Thanks to her good behavior, West was released two days early, and even allegedly spent one night having dinner with the warden.

These minor scandals eventually caught the attention of Hollywood executives and by all accounts helped launch West’s movie career. When she was 38 years old (an age when most actresses would be starting to wind things down), West landed a lucrative movie contract with Paramount Pictures. By 1935, she was one of the largest box-office draws in Hollywood and became the second highest paid person in America.

This “Police Station” scene was one of several instances where director Otto Preminger seamlessly switched from a real NYC location to a studio backlot through well-timed editing and great set design. In general, Preminger was known for minimizing the number of cuts in a scene, preferring to use a moving camera to capture the different angles, but obviously he embraced the use of editing in these instances so he could include the on-locaton footage. What’s particularly impressive in this scene is the meticulous detail of the set design, where the studio’s reproduction is almost indistinguishable from the real NYPD station house.

The scene works like this: it starts with a wide establishing shot of a squad car pulling in front of 345 W 47th Street in New York, then cuts to a shot of the two actors inside the car on a Hollywood backlot, where the camera stays on them as they get out of the car and enter the police station. Because the reproduction of the police station was so good, for a while, I thought Dana Andrews and Bert Freed were actually on location in Manhattan. But if you look closely at the two images above, you can see a slight difference in the lampposts and precinct sign. But the biggest aberration is with the neighboring building to the right of the station. On the Hollywood set, it juts out significantly, but on the actual 47th Street in New York, the fronts of the two buildings are more or less flush with each other.

But overall, the details of the police station facade are quite impressive, and could fool even the most savvy viewer into thinking we were still in New York.

Times Square

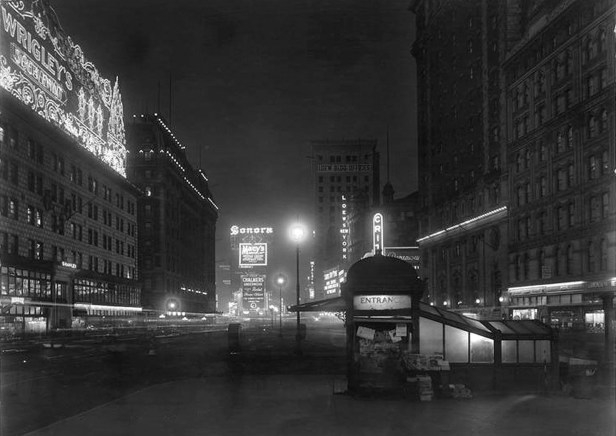

There wasn’t much confusion as to where this scene took place — it was clearly filmed in Times Square. However, because the scene was shot at night, and Times Square has changed so much over the years, it could’ve been a little difficult to figure out the exact spot where the action took place. But thanks to the presence of the subway kiosk to the left, I was able to zero in on the location.

I was pretty sure those old-style kiosks were only at one spot in Times Square. After consulting a few vintage photos and a clip from the 1928 film, The Crowd, I determined that the subway entrance was just north of the New York Times Building near W 43rd Street..

Like the “Police Station” scene above, this scene was made up of footage shot on a Hollywood backlot as well as footage shot on location in New York City. The wide shots of a car approaching the Willie character were real, but all the dialogue shots taken from inside the car were on a soundstage.

As I’ve already mentioned, this scene is part of just a handful of quick scenes that used on-location footage, which were mostly likely helmed by the uncredited second-unit director, Henry Weinberger. Interestingly, according to some sources, Preminger himself did extensive on-location filming in New York for over three weeks in early 1950, but after studio head Darry Zanuck demanded the story be changed, he ended up scrapping the footage. So now all we have left are these quick “establishing shots” of NYC without any dialogue.

But it might be noted that some of this second-unit footage of New York actually had character-actor Don Appell (who played Willie) there in person. I’ve seen this practice done in other films during this era (including Hitchcock’s Saboteur) where the crew brings in one low-level contract player from the studio to participate in the second-unit filming of New York (or anywhere else outside of California).

In Where the Sidewalk Ends, the second-unit team used Appell in this scene at Times Square as well as the following scene at a hotel on W 43rd Street, then used body doubles for any of the principal actors, like Dana Andrews. In Saboteur, they used character actor, Norman Lloyd (who, as of this writing, is still alive at 105 years old!), on location on Liberty Island, but used a double for Priscilla Lane.

It’s an effective way to link the footage of two different locations to make it feel like one continuous place.

Gambling at a Hotel

Since the previous scene with Appell was shot in Times Square, I assumed the location of this scene was probably somewhere nearby.

The first thing I turned to was that large congestion of neon signs in the background, one of which I hoped would help me figure out the location. (I chose to ignore the generic-sounding hotel sign on the building which I suspected was fake. And for added confusion, while the hotel sign said “45th Street,” later in the film, a radio dispatch calls it the “43rd Street Hotel.”)

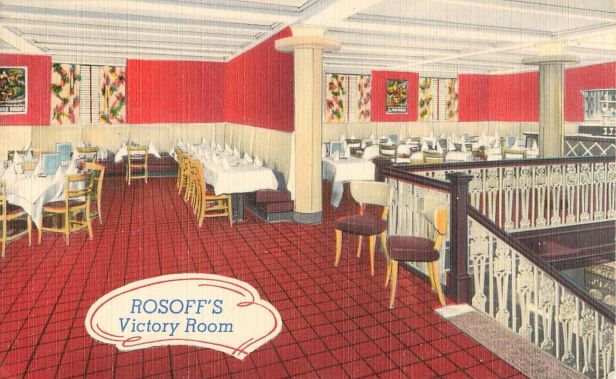

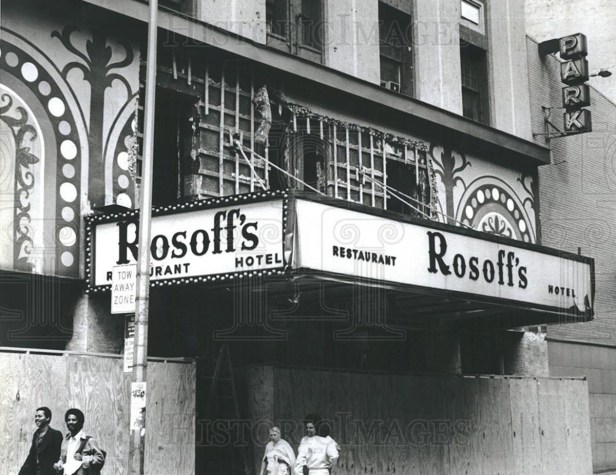

There were lots of neon signs from this scene to choose from, but the one that ended up helping me nail down this location was for “Rosoff’s Restaurant Hotel Bar.” Since the name was unique enough, and (as it turned out) the restaurant was well-known enough, I was able to find an address fairly quickly.

Rosoff’s Restaurant and Hotel was a fixture at 147-151 W 43rd Street Street for over 60 years, and had a somewhat obtuse motto: “ALWAYS SOMETHING GOOD TO EAT.” Split up into several different themed spaces —such as the Manhattan Room, the Coach Room, and the Wedgwood Room— Rosoff’s was the first major New York restaurant to institute a ”no smoking” room on the premises in 1974.

The owner was Max Rosoff, a Russian-born immigrant who came to New York as an orphan at age 12. He began his catering career as a deli meat slicer for a salary of $3 a week and worked his way up to become a renowned Times Square restauranteur who would play host to some of New York’s biggest celebrities. But it was those humble beginnings that probably later inspired his charitable efforts, like offering free meals to the destitute during the Great Depression, or accumulating a surplus of $1,000 through “reduced butter costs” during WWII and donating the proceeds to military relief funds.

After Max died in 1962 at the age of 82, the restaurant managed to remain a popular destination for several more years, although it wasn’t necessarily adored by pugnacious foodies. In a 1968 restaurant guidebook, the reviewer gives the restaurant’s Victory Room a zero-star rating, scoffing, “The menu is American, the portions are copious, and the boast of the menu is ‘All you can eat.’”

Rosoff’s eventually closed in the spring of 1981 after its lease was bought out by the O’Neal brothers — a pair of restauranteurs who owned several other establishments in Manhattan. Although somewhat anticipated, the sudden closure of the business caught a lot of the staff off-guard. So much so, management had to wait a few extra days before they officially closed the hotel in order to give the guests time to find other accommodations.

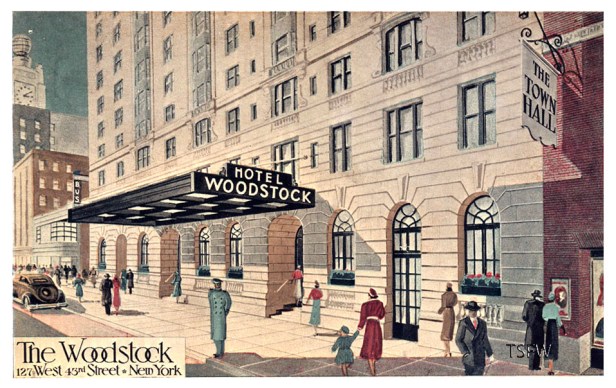

Once I figured out where Rosoff’s was located, I was able to conclude that in this scene, the Willie character went inside the Hotel Woodstock at 127-135 W 43rd Street.

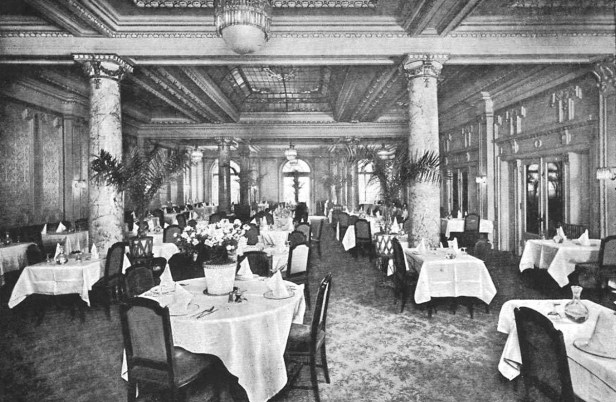

Built a half-block east of Times Square in 1903, the 12-story hotel (originally called the Spalding) opened for business just as the neighborhood was transforming into a hub of thriving entertainment. The new luxury hotel on 43rd —which accommodated not only visiting tourists and businessmen, but permanent residents as well— was designed to astound. The exterior was made of stylish limestone with French-inspired iron balances, while the interior was decorated “in the style of Louis XVI,” and adorned with things like polished marble columns and immense stained glass skylights.

The Woodstock’s well-accoutered rooms appealed to some of the country’s most wealthy, such as “Diamond Jim” Brady and then-future President Woodrow Wilson, who made the hotel their permanent home, giving them access to a multitude of relaxing amenities, such as a parlor, library, ballroom, and a bunch of bars and dining areas. By mid-century, as many of the other Times Square hotels started to become rundown flop-houses, the Hotel Woodstock made a concerted effort to remain a respectable place. But by the 1970s the city’s economic woes caught up with them, and the time-worn Woodstock was carved up and sold off, with the majority of the space taken over by the nonprofit organization, Project FIND.

As of this writing, the Woodstock is still open and run by Project FIND, who continue to operate it as a SRO hotel for low-income, elderly New Yorkers.

Before I figured out that this scene was filmed at the Hotel Woodstock on 43rd street, I got a little sidetracked when I investigated a curious neon sign in the background that read, “MIDTOWN BUS TERMINAL.”

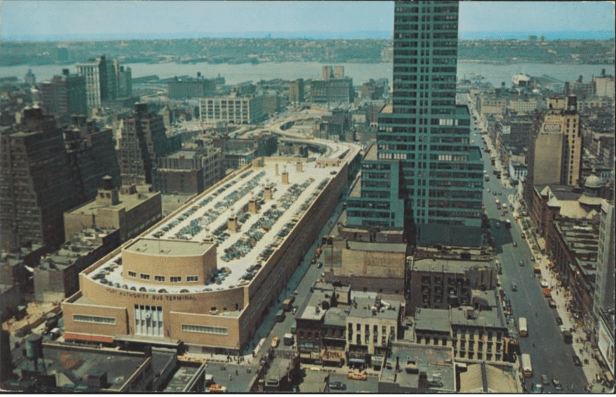

Turns out this terminal (located at 143 W 43rd) served the Greyhound Bus Company, which surprised me since I assumed most Greyhounds came in and out of the nearby Port Authority Bus Terminal. But actually, at the time Sidewalk was being filmed, PABT was still months away from officially opening. And before that, New York City was full of many different independent bus companies who had stations spread all over Midtown Manhattan, which caused a great deal of commuter havoc.

According to the 1939 edition of the WPA Guide to New York City, the chief bus terminals in Manhattan were the All American Bus Depot on W 42nd St, Capitol Greyhound Terminal on W 50th, Consolidated Bus Terminal on W 41st St, Dixie Bus Center on 42nd St, Gray Line Terminal on W 36th St, Pennsylvania Motor Coach Terminal on 34th, and the Midtown Bus Terminal on W 43rd, which was featured in this scene.

This large consortium of bus companies weren’t just limited to operating out of traditional stand-alone depots. During this time, it was not unusual for a luxury hotel to have their own private bus station in their building to give their customers the opportunity to travel directly to their property.

For example, the Hotel Dixie at 250 W 43rd Street, on the block west of Times Square, had one of city’s largest indoor facilities (unlike most bus stations which had to rely on curbside service). The Dixie Bus Depot (also known as the Dixie Bus Center or the Central Union Bus Terminal) began operations in the late 1920s, just as vehicular travel was beginning to compete with rail service. One unique feature of the underground depot was a 35-foot turntable that spun the bus around so it could line up with one of the exit ramps or one of the narrow parking stands. It was an ingenious way to get the maximum use out of a compact space.

Back in 2013, professional location scout and author of the blog Scouting NY, Nick Carr, investigated the extant Dixie building which has since become a parking garage. After descending to the lower level, he was amazed to discover that the huge turntable was still there! (Although, at the time of this writing, major renovations are being made to the property, so it’s possible this relic from the early 20th century is now gone.)

I don’t know if passengers from the 1930s and 40s were thrilled by a rotating floor, but the Dixie’s inventive use of minimal space helped keep the depot a busy destination. During its peak seasons, the hotel’s terminal used to handle up to 350 buses a day. One New York Times article from 1946 described a particular busy day where stretches of charted buses lined 43rd Street, and hundreds of long-distance travelers were turned away because their carriers had no more room.

However, after the nearby Port Authority Bus Terminal opened at the end of 1950, a lot of bus companies stopped using the facilities at the hotel. At the start of 1957, there were only two bus lines operating out of the Dixie Bus Depot, and by the summer of that year, the owners were forced to close their doors after 29 years of service.

On the other side of 43rd Street, the Midtown Bus Terminal, which was featured in this scene, caved more quickly, shutting down and selling its property within months of PABT’s opening.

One by one, smaller bus depots throughout Manhattan closed their doors as the bus lines moved their services wholly to the consolidated PABT. The one notable exception was Greyhound, who still had a couple high-volume stations in Midtown Manhattan, including one next-door to the old Penn Station, providing a convenient train-to-bus transfer.

Located just north of the famed train station between West 33rd and West 34th Streets, Greyhound’s stand-alone building continued to have a thriving bus business for many years after Port Authority’s opening. In fact, Greyhound was doing so well, the company tried to build a new, larger bus terminal on their 34th Street site. However, their plans were rejected by the city Administration, citing a 1947 rule barring any new bus stations (or enlargements of exiting ones) in the Midtown Manhattan area, east of Eighth Avenue.

The proposed $10 million, 4-story terminal was finally terminated a year later, but Greyhound continued to resist pushes by the city to move into PABT, not wanting to share a space with mostly commuter lines. Then, after years of standoffs and negotiations, Greyhound finally agreed to move its 200 daily buses to the terminal in 1962, for an annual rent of $1.2 million. The days of competing bus stations was finally over, and Port Authority Bus Terminal essentially became the sole operator in Midtown Manhattan.

When Port Authority was completed in 1950, it took up less space than what it does today, only occupying the block between 40th and 41st Streets. And it wasn’t until I was doing research for the Midtown Bus Terminal in connection to this film that I saw what the PABT building used to look like before the expansion and upgrade in the 1970s. The $24 million structure was a magnificent example of sleek Art Deco design, with a light brick exterior, modernistic geometric accents and soaring curved walls, making it look like a bolder version of the Guggenheim.

Despite facing opposition by the ever-obstinate Robert Moses and some of the smaller bus stations, PABT received much fanfare when it finally opened on December 15th, 1950, hosting a packed celebration inside the immense concourse. Cushman Sons, Inc., a bakery that had a shop inside the terminal, distributed pieces from an 8×16 foot, 800-pound cake to an estimated 5,500 visitors in one day.

Yet, as successful as PABT was in its early years, it was clear the facilities were not enough to handle the solid stream of bus traffic coming in, and the transportation agency sought $550 million for continued renovations. But the terminal didn’t see any large-scale improvements for nearly ten years, when three parking levels were added to the roof in 1960, creating enough space for a thousand cars. In the ensuing decades, the renovations were minimal and seemed to only make the already-confusing layout worse. And as the city’s economic troubles began to rise, so did the criminal element, which tended to congregate at the deteriorating bus terminal.

It wasn’t until 1979 that Port Authority finally began what was its second major construction project, primarily concerned with increasing its size by extending its footprint to 42nd Street. Completed in 1981, the extensive reconstruction involved covering up the terminal’s sleek Art Deco facade with darkly painted exposed metal beams, making the new, modern PABT a definite eyesore.

The new grim aesthetics suitably matched the terminals’s affinity for attracting criminals and derelicts. I personally have a vivid memory from 1985, when I used to cut through the bus station to get from 8th to 9th Avenue, of seeing a man absently walking through the concourse with blood streaming from his forehead and no one paying any mind to him. This was also a period when you’d commonly see clusters of heroin addicts hunched over in a somnambulistic state outside the building’s entrances.

This drab and depressing “modernized” bus terminal would be featured in a several 80s films, such as Desperately Seeking Susan (1985) and The Secret of My Success (1987). Even though it’s been slightly cleaned up in recent years, today’s PABT is still an ugly eyesore and is no more pleasant to visit.

Paine’s Apartment

Like most of the other scenes from this film, finding this location wasn’t too difficult. The most obvious clue was the Manhattan Bridge looming in the background, and thanks to research I did for 1956’s Somebody Up There Likes Me, I was already pretty familiar with this particular vantage point. There was a scene from Somebody that took place on Pike Street, and had almost the exact same view of the bridge as what appears in Where the Sidewalk Ends. So, assuming this quick night scene also took place on Pike, I searched through the 1940 tax records until I could find a photo of a matching building, mostly focusing on that prominent corner building on the left side of the frame.

That building turned out to be 59 Pike Street, which used to be on the southeast corner of Monroe Street. The six-story apartment building got torn down in the early 60s to make way for the Rutgers Houses, a public housing development.

The way Preminger was able to smoothly mix on-location footage with stuff he filmed at Fox Studios was very impressive. This was done with a simple edit between the wide shot of Pike Street and a medium shot of the Hollywood set featuring a realistic tenement facade, making the cut just as Andrews opens the car door. It was such a seamless cut, I had to double check the 1940 tax photos, just to confirm it was, in fact, a set. By my calculations, if the apartment was real, it would have been located at 44 Pike Street.

I was already pretty sure Paine’s apartment building wasn’t a real NYC location —even before checking the tax records— but since production did a near spot-on reproduction of the 47th Street police station, I was curious to see if they matched 44 Pike as well. However, not only did the Hollywood facade not match any of the former NYC tenements on Pike Street, but Paine’s apartment would have been located at what was then an empty lot.

It might be noted that the building number in the film was 58, presumably making it 58 Pike Street. But that would’ve been an impossible address because that just happens to be the only lot number that didn’t exist back in 1950. The street numbers go from 56 on the north corner of Monroe, then jumps to 60 on the south corner, skipping 58 altogether. I assume this was just an unplanned happenstance, and not by design. (Of course, that didn’t stop someone from listing 58 Pike Street as one of the filming locations on IMDB.)

In addition to a recreated New York apartment building, production also built a makeshift parking lot next-door with an expansive rear projection set up behind it, giving us the feeling we were a stone’s throw away from what looks like an El train. But as good as these methods were for replicating Manhattan’s Lower East Side, they still couldn’t beat the real thing, and makes me wish Preminger was able to use at least some of the extended footage he shot before the studio-demanded rewrites.

From what I’ve read, this footage most likely included neighborhoods besides Midtown and the Lower East Side. In his book, Film Noir FAQ, author David J. Hogan writes, “Preminger and cinematographer Joseph LaShelle shot on location in Manhattan and Washington Heights,” but he doesn’t offer any further details, which could be a little misleading to his readers. (It’s also unclear why he distinguished Washington Heights from Manhattan since Washington Heights is already in Manhattan.) I’m assuming Hogan was referring to the aforementioned footage that was ultimately discarded, but since I haven’t gotten access to any detailed production notes, I have no idea if Preminger ever shot in Washington Heights or not.

Regardless, this perfunctory reference to Washington Heights has since been distorted and misrepresented on several movie websites, giving the impression that the final version of the film contains footage actually shot there. It’s possible they think the scenes taking place at Morgan’s father’s apartment were shot on location in Washington Heights, but that would be rather stupefying, considering it was clearly shot on a Hollywood set with a miniature George Washington Bridge in the window.

Bottom line, I feel pretty confident in saying that the final cut of Where the Sidewalk Ends contains only five NYC locations (not including rear projection footage), and none of them take place in Washington Heights.

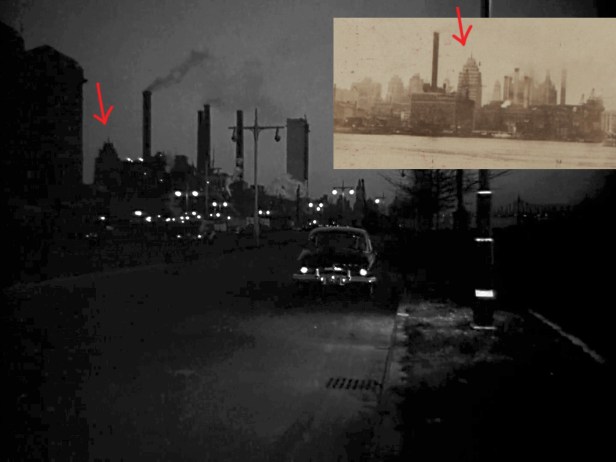

East River Drive

This is the last quick scene that was shot on the the streets of New York, taking place on FDR Drive — although, in the movie, the Willie character refers to it as “East River Drive,” which was its name prior to President Roosevelt’s death in 1945. (I guess some people were slow to adjust to the name-change, the same way I still refuse to call the Triborough Bridge the RFK Bridge.)

Even though the night footage was dark, I could make out a few key buildings in the background to help me confirm this location, including the Woodstock Tower (no relation to the hotel featured in an earlier scene) and the newly-constructed Secretariat Building at the UN Headquarters.

So by my calculations, the place Willie tells Dixon to go to (i.e., East River Drive behind Bellevue), was pretty much the same place production shot this quick scene. Of course, they shot all the stuff with Dana Andrews on a soundstage in California, and used a body-double for the one wide shot they did in New York.

What’s interesting is how many different techniques they used in Hollywood to recreate the streets of New York. They used sets, backlots, rear projections, and in this scene, what looks like a large backdrop of Bellevue Hospital. Even though the backdrop is not totally believable, it has a sort of whimsical quality to it that manages to capture the lonely, ethereal nature of NYC at night, like something from the canvases of Stuart Davis or Edward Hopper.

As a sidenote, the presence of the United Nations Secretariat Building in a 1950 film confused me for moment because according to Wikipedia, construction wasn’t completed until 1952. But as I should know by now, you can’t trust everything you read on the web. Turns out whoever made the edits on the Wiki page mixed up the 1952 completion date of the entire Headquarters (which comprised of several different structures) and the 1950 completion date of the Secretariat office building (which was the first structure to be completed and fully occupied).

But not to worry, the Wiki page was swiftly corrected by yours truly, with all the proper citations.

When evaluating Where the Sidewalk Ends, people invariably compare it to Preminger’s earlier effort, Laura, probably because both are noirs with the same two leads. And more often than not, they would contend that Laura is the superior film. It was certainly more successful at the box office, and better remembered today, often cited in modern lists as one of the top film noirs of all time. But I think both titles have admirable (but different) qualities that should be appreciated.

I can’t really argue the merits of Sidewalk, compared to Laura, in terms of theme and story analysis, mainly because that’s just not my area of expertise, or rather, I find myself rarely aligned with the general consensus among cinephiles. However, when it comes to cinematography, I think Sidewalk is richer, more textured, and a better example of what one would consider a classic “noir look.” In addition, Sidewalk better captures the look and feel of old New York than Laura. In fact, in my mind, I always remembered Preminger’s earlier film as having taken place in Los Angeles, and it wasn’t until I rewatched it recently that I realized that it, too, took place in New York City.

Besides the fact that there wasn’t any location shooting done in NYC, the settings in Laura feel like they could be in any mid-20th century metropolis, while Sidewalk has several nice NYC touches; like the little old lady who sleeps by her window in Paine’s apartment building; or Martha, the wisecracking owner of a Greenwich Village cafe, who knows all her customers on a first-name basis.

Besides the fact that there wasn’t any location shooting done in NYC, the settings in Laura feel like they could be in any mid-20th century metropolis, while Sidewalk has several nice NYC touches; like the little old lady who sleeps by her window in Paine’s apartment building; or Martha, the wisecracking owner of a Greenwich Village cafe, who knows all her customers on a first-name basis.

Plus, many have noted that Dana Andrews’ character in this film is basically an extension of the one he played in Laura, but with more cynicism and questionable morality, which better reflects the hardened quality of your typical New Yorker.

On that subject, I think Dana Andrew’s performance in this film is one of his best, playing each scene with multiple levels of compassion, annoyance and duplicity. In several scenes where Dixon is interacting with his police department, you can see his brooding anger just below the surface, while at the same time, there are glimmers of suppressed panic as he knows he could be caught for his crimes at any second. But Andrews plays it cooly, letting us see that he’s constantly thinking of his next move, but never tipping his guilty hand to his fellow men in blue.

Gene Tierney, on the other hand, I think is the weakest link in the cast. Personally, I’ve never been much of a fan of hers, and she plays the part of Morgan so flatly, that I can’t see any reason why Andrews’ character would fall madly in love with her. Some critics have pointed to an underwritten character in Ben Hecht’s script as the reason for Tierney’s less-than-memorable performance, but I think if you had someone like Barbara Stanwyck or Ida Lupino in the role, they’d find ways to flesh out the character, adding to it a certain amount of gusto.

But the real story is with Dixon, and it’s his interaction with the other characters in the story —whether its Karl Malden as the hard-nosed lieutenant, Tom Tully as the tough but lovable father of Morgan, Ruth Donnelly as the matriarchal cafe owner Martha, or Gary Merrill as the smugly evil Tommy Scalise— that really draws us in. The filmmakers have created a dark, fallowed world with multiple layers of both cynicism and hope, full of unique characters, shadowy corridors, and a story that feels like it could be one from a million told from the streets (or sidewalks) of New York.

Amazing. Reminds me of the photography book: NY then and now. Seeing movie clip locations is just as rewarding.

LikeLiked by 2 people

A fantastic, thoroughly researched job! Just discovered your site when Google searching Where The Sidewalk Ends for my latest Noir drawing. Your pinpointing of actual locations and then and now comparisons really help to make sense of blurred, gloomy film stills. Just read WTSE, The Lost Weekend (which I have already drawn year ago) and Somebody Up There Likes Me. Very impressive!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for your comment John. I checked out a few of your illustrations. Great stuff. I really like the extra insanity you added to Ray Milland in your “Lost Weekend” drawing. I’ll keep my eyes open for your rendition of “Where The Sidewalk Ends.”

Keep on inkin’!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi, very good article, but the photo “A rare color promotion photo for Where the Sidewalk Ends, with Dana Andrews and Gene Tierney” is from “The iron curtain”, the fourth film with those two. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0040478/

LikeLike

According to Getty Images, the photograph was from “Sidewalk,” but based on the wardrobe, I’m pretty sure you’re correct that it was from “Iron Curtain.” I have since noticed that Getty will sometimes get credits wrong, especially for vintage photos. Thanks for the callout.

LikeLike

The Google Earth Street View of 73 Monroe Street, NYC looks like a good model for a movie set.

LikeLike

Amazing job on research. Fantastic website.

LikeLike