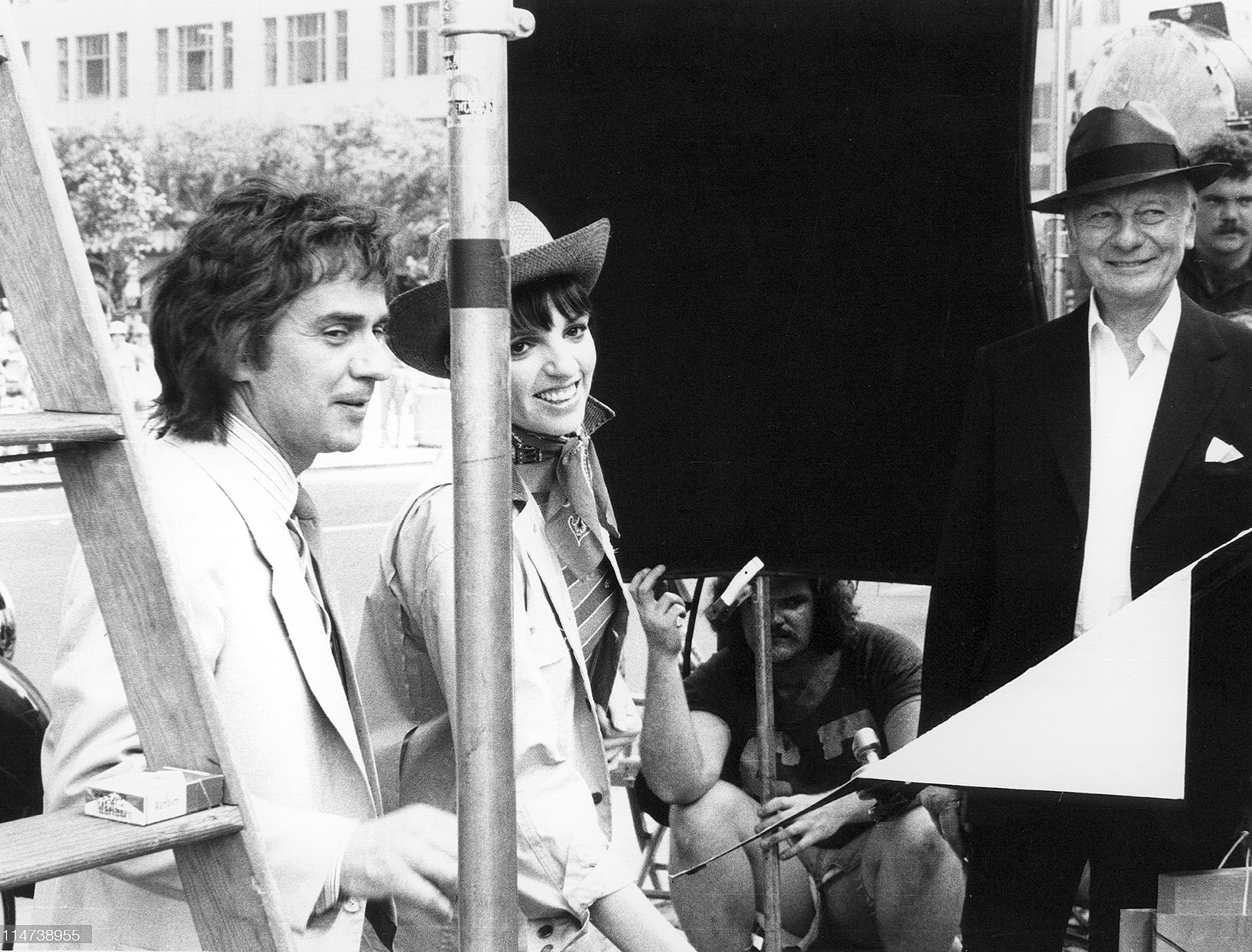

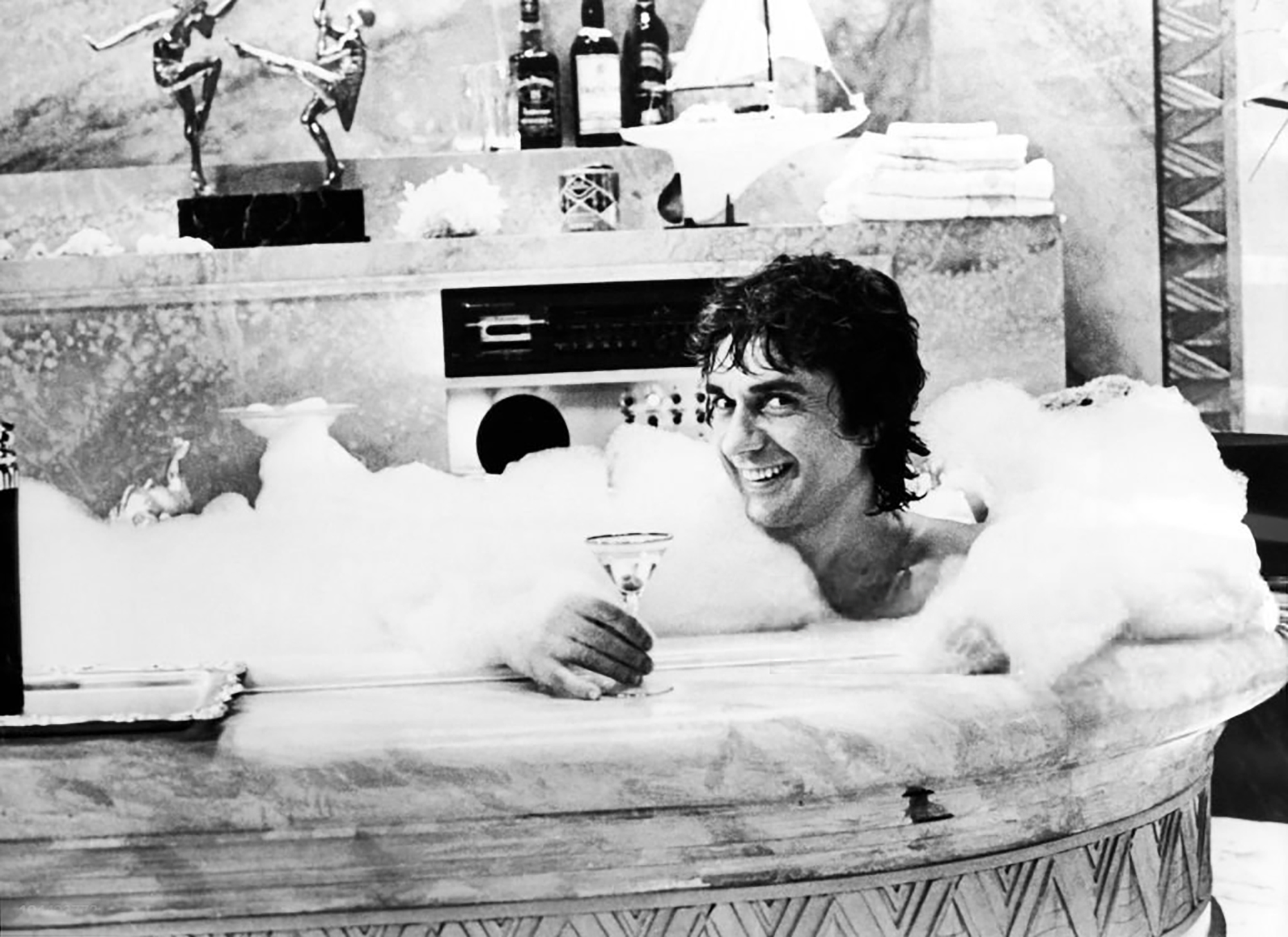

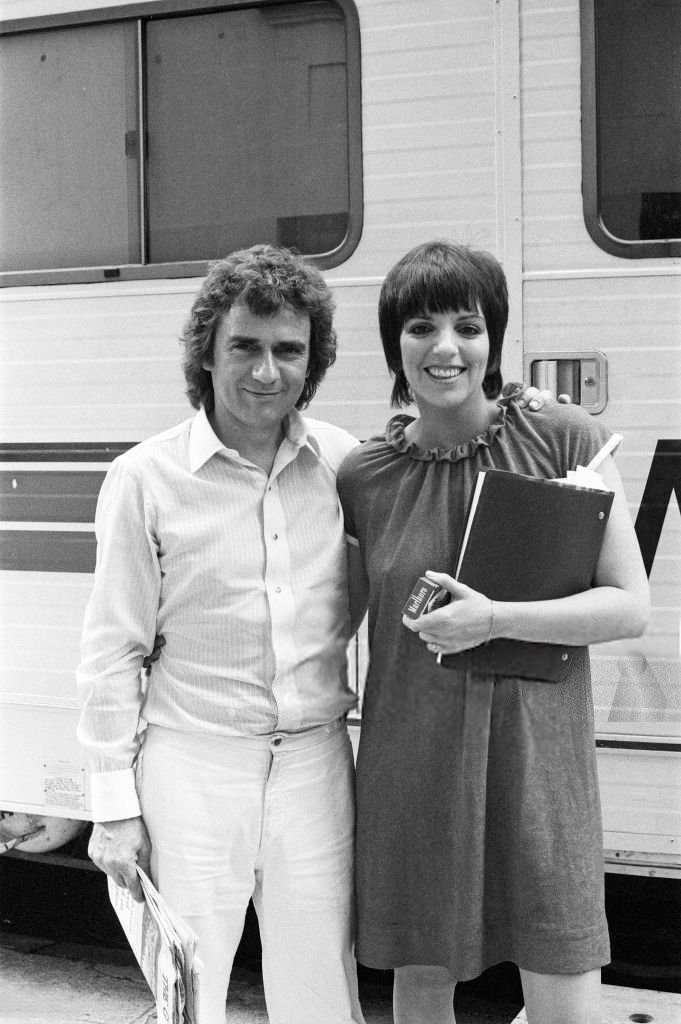

A sleeper hit from 1981, Arthur is centered around a childish millionaire (Dudley Moore) who’s in a perpetual state of drunken goofiness, spending most of his nights carousing with prostitutes, and most of days being put in his place by his acerbic butler (John Gielgud). His playboy days get more complicated when he falls in love with a blue-collar waitress from Queens (Liza Minnelli), while at the same time is being pressured into a loveless marriage by his imperious family.

Led by standout performances from its three leads, Arthur succeeds as a high-spirited screwball comedy, supplying an ample amount of great one-liners as well as some touching, heartfelt moments. While writer-director Steve Gordon’s script has a few rough edges, like its flawed titular character, it manages win you over by the end.

Unlike many NYC-set movies of the 1980s, Arthur was filmed entirely in the Tri-State area, without the benefit of Canadian Streets or Hollywood sets. In fact, as far as I can tell, very few sets were used at all, and the ones that were used were built on one of the city’s few studios operating at the time — Kaufman in Astoria, Queens.

Picking Up a Hooker

When I began my research on this film, there were quite a few locations already identified, but there were still a decent number of holes, and this opening scene was one of them.

It was already established that a lot of the Manhattan locations were on the east side, so I figured this probably took place there too. And judging by the width of the street, it was clear they were on an avenue.

Another major clue was the number 615 on an awning behind the two streetwalkers, which I assumed was not set dressing.

So I searched for any 615 building on the east side in Google Street View, but nothing looked right. After double-checking each avenue and finding nothing promising, I started thinking maybe the awning was set dressing with a fake address. That’s when I asked my research partner Blakeslee to take a stab at it.

He ended up taking a different tactic, focusing instead on what looked like a set of domes in the background. Figuring they were part of a synagogue, he searched eastern Manhattan for any Jewish congregations and eventually came across Central Synagogue at 652 Lexington Avenue. From there, he identified one other extant building on a neighboring block and concluded that the scene took place on the corner of 53rd and Lexington.

And it turns out that that Lexington Avenue corner is, in fact, number 615, even through it wasn’t where I ended up when I did my initial search on Google Maps. Apparently what happened was, when a bunch of the smaller buildings on Lex got torn down and replaced with large skyscrapers in the eighties, several address numbers got eliminated, including 615. So when you plug that address into the search box, Google Maps makes an estimate and takes you one block to the north.

When all this redevelopment was happening thirty-forty years ago, 615 Lexington and all its neighbors were torn down and replaced with 599 Lexington, a 50-story, monolithic skyscraper. One year after it was completed, the block-long building was used as the office exterior in the Michael J Fox romantic-comedy, The Secret to My Success (1987).

Driving Through the Park

Plaza Hotel

The Oak Room

This long sequence of going from the Lexington Avenue street corner to the fancy restaurant didn’t have any locations that were hard to find. The Plaza Hotel and its famed Oak Room are landmark spots in NYC and easy to identify. And while the driving scenes were not as obvious, they all had distinguishing visuals —like the median strip on Park Avenue— that helped me find them fairly effortlessly.

Another thing that helped was they stayed somewhat geographically accurate — going from 53rd and Lex to 67th and Park, then into Central Park at 72nd Street, driving south through the park, and ending up at the Plaza on Central Park South..

Amazingly, the Oak Room, the elegantly paneled, German Renaissance Revival-style dining venue where Arthur and his “date” have drinks has remained vacant for over a decade.

Known as the Oak Lounge when it opened in 1907, the space served as a men’s club until 1934 when it became a restaurant and renamed the Oak Room. Starting in the late 1940s, women were allowed in the Oak Room during the summer evenings, but the restaurant was still predominantly a male hangout.

Over the next ten years or so, women were incrementally given more access. But it wasn’t until 1969, after several vocal protests from the feminist group, NOW, led by human rights activist Eleanor Holmes Norton, that women were allowed in there year-round with no restrictions.

After that, the Oak Room held a solid position as one of NYC’s most fashionable restaurants for the rich and famous. This lasted until 2011 when it suddenly closed.

One reason for the closure stemmed from a claim by the owners of the hotel that the leaser of the Oak Room failed to pay nearly a million dollars in back rent. But the major point of contention was the private parties that were being held in the restaurant on the weekends. These events often involved rowdy behavior, illegal drug use, and loud music. They were described in the New York Post as a “champagne-fueled orgy of gyrating jet-setters” and purported by the hotel owners to be undermining the Plaza’s elegant reputation.

Today, the space is mostly unused but is occasionally rented out for special events — minus any orgies.

Arthur’s Apartment

Arthur’s Father’s Office

The exteriors of Arthur’s penthouse apartment and his father’s office building were already identified by several sources when I began my research on this film. I also found out from The Film Encyclopedia that Arthur’s lavish penthouse interiors were sets built at Kaufman Studios in Astoria, Queens.

I couldn’t find a reference to any other interiors that were shot there, but if I were to guess, I’d say the office was also probably a set.

Meeting Linda

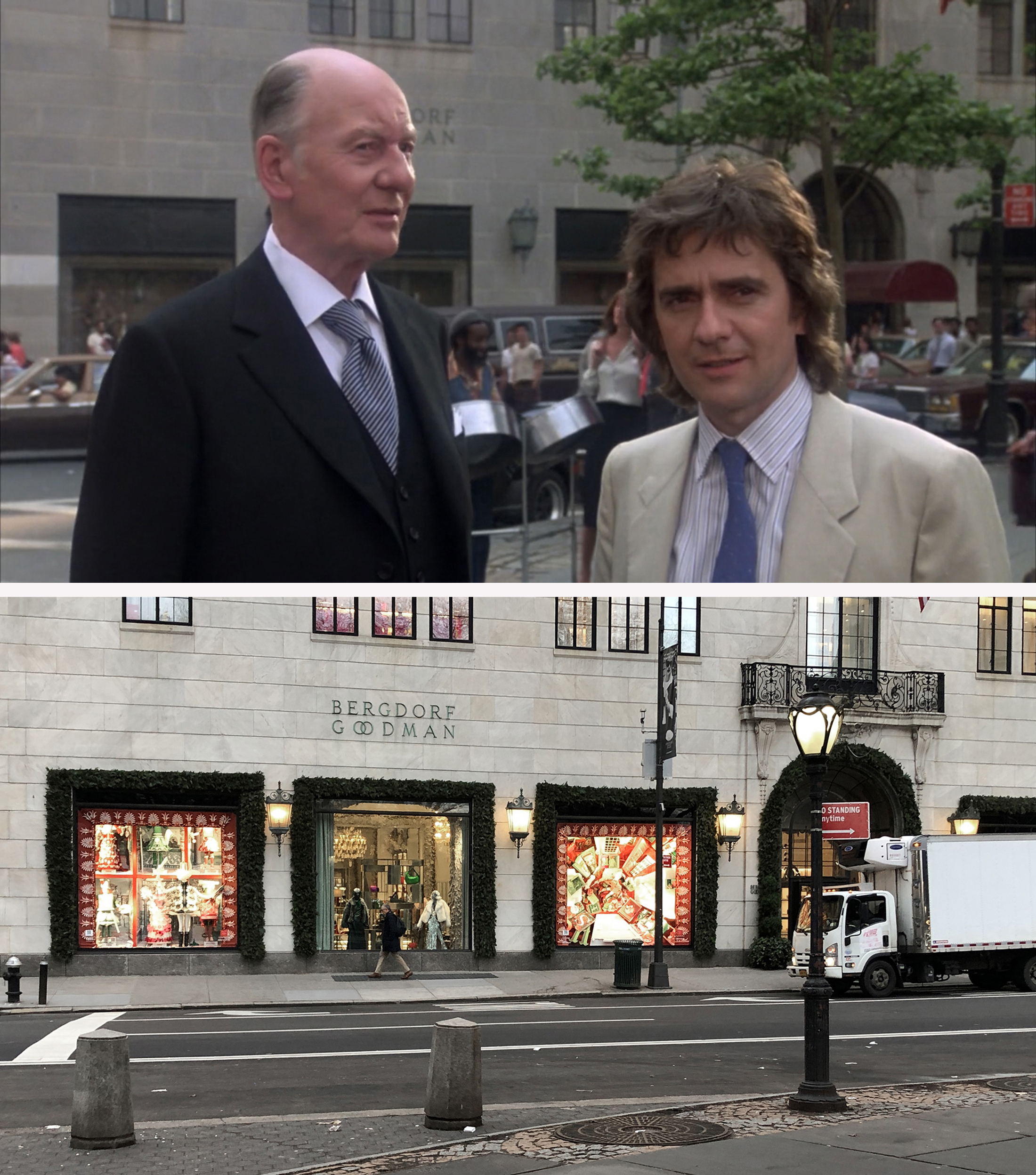

Like the Plaza Hotel, Bergdorf Goodman was easy to identify, especially since the movie features one of its signs in the establishing shot.

I did have a little trouble figuring out what set of doors the characters exit when they leave the store because the facade along Fifth Avenue has changed over the years. But after studying the reflections in the windows, I concluded they used the mid-block exit on Fifth.

I also should call out the man playing the security guy is Irving Metzman — one of my favorite character-actors of the eighties. He would later play the doorman in 1986’s Crocodile Dundee just a few feet from this filming location at the Plaza Hotel’s Fifth Avenue entrance.

Linda’s Queens Apartment

This was one of the first locations I found for this movie, and at the time, I was very proud of myself for figuring it out. (Of course, this was during the early stages of this project, so my detective skills were still being developed.)

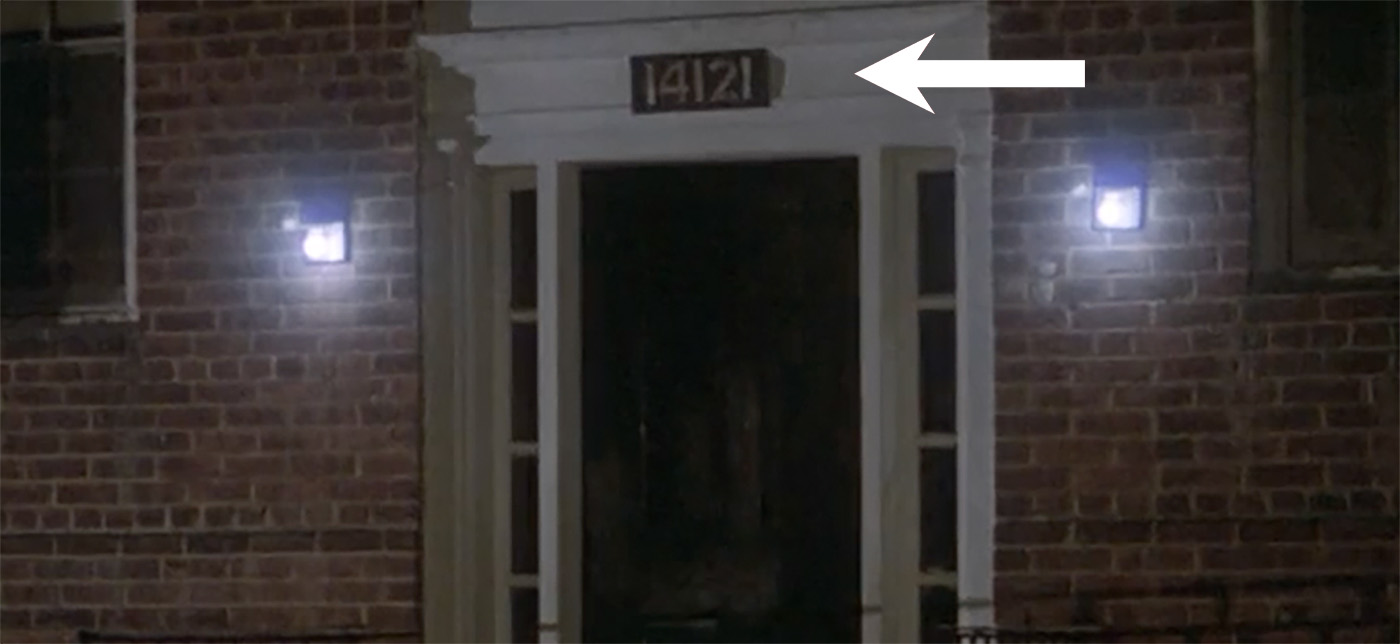

The big clue was an address number of 14121 that appeared in a later scene at the same location.

The way the numbering is done in Queens is different from any other borough and can be a little confusing at first. Basically, the address number always starts with the nearest cross street to the west of it, and it’s followed by a number that progresses as you go from west to east (although they often skip numbers along the way). So, a building with an address of 14121 would be in the middle of a block to the east of a roadway with 141 in it. But to add to the confusion, Queens usually has the same number in a variety of roadways, so it could theoretically be east of 141st Street, or 141st Avenue or 141st Place, etc.

As it turns out, 141st Street is the only one that is a major thoroughfare in Queens, so that was naturally the logical place to start. And fortunately, in this first scene taking place at Linda’s apartment, you can see the street they’re on appears to end at a park.

So, I began looking along 141st Street for any place that had a park or playground on one side of it.

I eventually came across a playground along 141st in the Kew Gardens Hills section of Queens. There were two streets that dead-ended at the city park — 78th Road and 79th Avenue — and both of them had buildings on them that matched the ones in the film with an address of 14121. I ended up concluding they were on 79th and not 78th simply based on the traffic direction of the street.

(And by the way, these days, most Queens addresses now include a hyphen to make it a little easier to decipher. So, as you can see in the modern pictures above, Linda’s building is displayed as 141-33.)

As I mentioned earlier, Arthur’s penthouse apartment was a set built at Kaufman’s, and I believe the interiors of Linda’s apartment building were a set as well, especially since the real hallway at 141-33 79th Avenue is dramatically different from what appears in the movie.

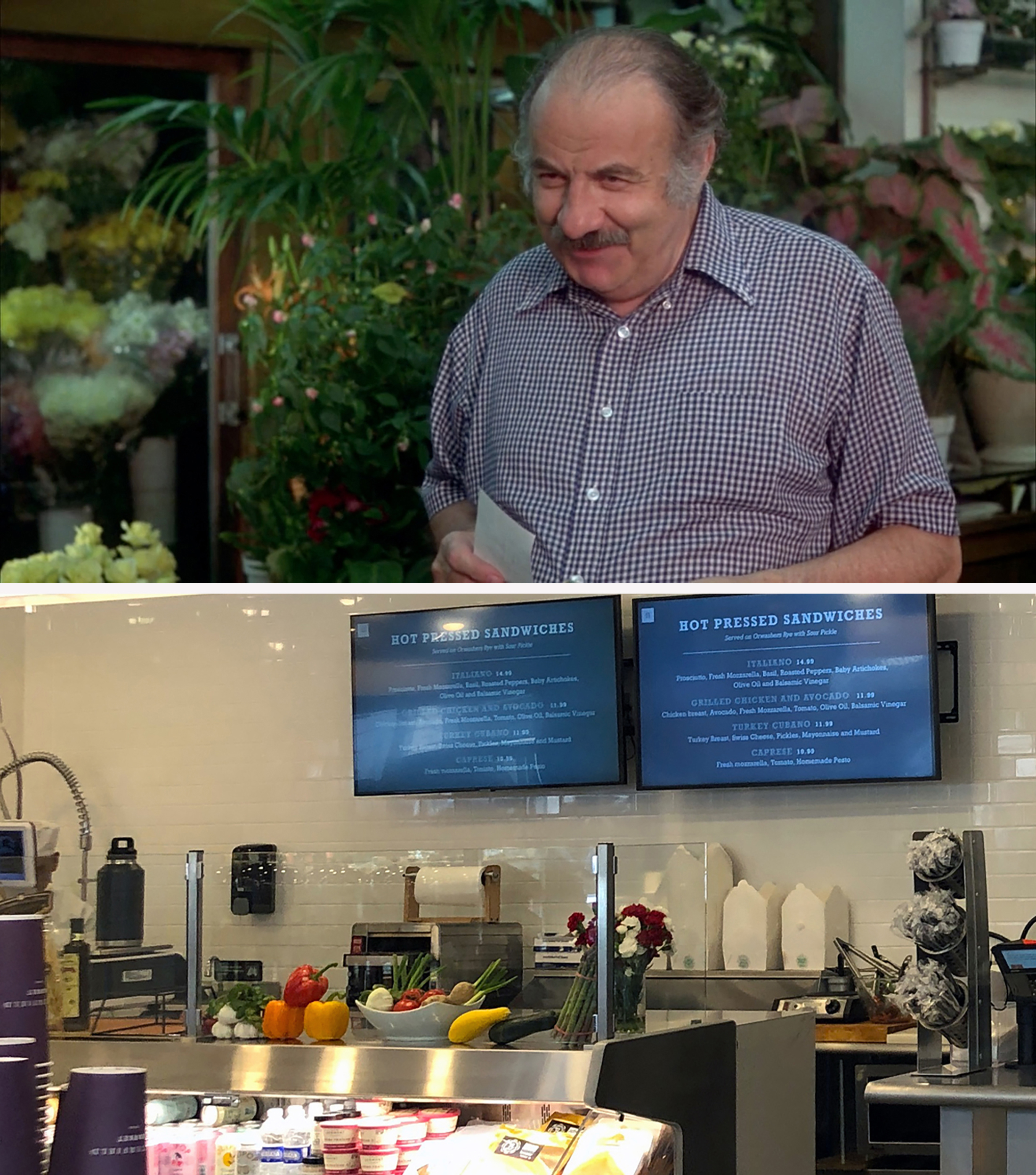

Flower Shop

This was another location I found that had previously been unidentified. There wasn’t much to go on other than a hunch that it was filmed on Manhattan’s East Side. So the first thing I did was a basic search in Google Maps for any flower shops in the vicinity. I knew the chance of the same flower shop still being around was low, but I knew of at least one other florist that has lasted for over 50 years so I thought it was worth a shot.

I soon zeroed in on a Windsor Florist at 1118 Lexington Avenue, which looked very promising since it was only a half block away from another established filming location. Plus, just like in the movie, it was in a corner building, offering up a very similar layout.

From there, I went searching through an old Manhattan phone book to see if Windsor Florist was at 1118 Lexington back in 1981. To my surprise, not only was it in business there in ’81, but it actually dated back to 1936.

Located on Lexington for nearly 90 years, the shop had to close its doors in 2022 after a legal dispute with Ferl Realty Company. But there’s still a location on Second Avenue, operated by Sam Karalis, who inherited the business from his family.

It might be noted that across from its Lexington location, at no. 1117, there was one of the first three Starbucks to be established in NYC in 1994 (with obviously many more to follow). The Seattle-based coffee shop closed in 2019 right before the building was razed.

Arthur and Linda’s Dinner Date

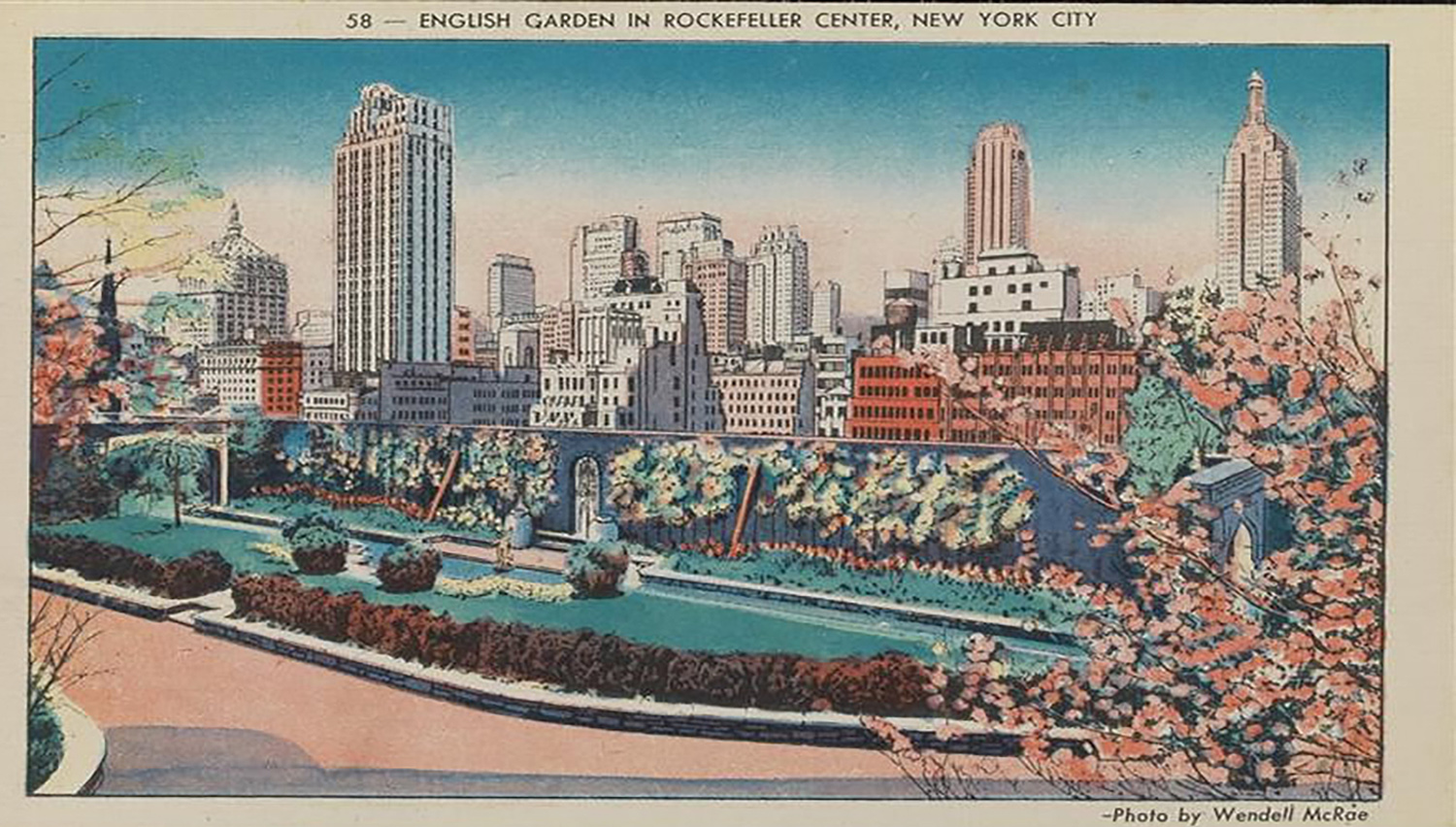

Back when I was researching this film, I couldn’t find any information as to where this date scene took place. However, with the iconic St. Patrick’s Cathedral seen across the street, it was obvious that it was shot on a rooftop at Rockefeller Center. And judging by the angles, I determined that they were on the northern wing of the International Building, best known for displaying a giant Atlas statue outside its Fifth Avenue entrance.

While finding the location was fairly simple, I must admit that at the time, I had no idea there were these private gardens in Rockefeller Center.

These rooftop gardens on four of the Fifth Avenue buildings were part of architect Raymond Hood’s original 1930 vision of this midtown complex. In addition to these formal gardens (accoutered with evergreen hedges, cobblestone walkways and fountains), Hood proposed building a network of bridges connecting the green rooftops together. But time and money nixed those plans.

These rooftop gardens on four of the Fifth Avenue buildings were part of architect Raymond Hood’s original 1930 vision of this midtown complex. In addition to these formal gardens (accoutered with evergreen hedges, cobblestone walkways and fountains), Hood proposed building a network of bridges connecting the green rooftops together. But time and money nixed those plans.

That’s not to say what was created wasn’t breathtaking. One of the smaller gardens at 30 Rockefeller Plaza was packed with eye-catching amenities which included a bird sanctuary, a vegetable garden, rock gardens and a children’s garden.

The rooftop garden on the International Building at 630 Fifth Avenue, which was used for this scene, was designed by floral expert A.M. Van den Hoek, and is one of the Center’s original botanical creations that still survives today. Sadly, these lush spaces are restricted to private use and can only be viewed by tenants in the surrounding buildings or the wildly rich who can afford to rent the space.

It should be said, the rooftop garden’s cinematic appearance hasn’t been limited to this 1981 comedy; it’s been featured in a bunch of film and television productions over the years.

Most notably, it was used in 2002’s Spider-Man where the flying superhero alights onto the International Building’s south wing rooftop to get Mary Jane out of harm’s way.

.

Arthur and Linda at an Arcade

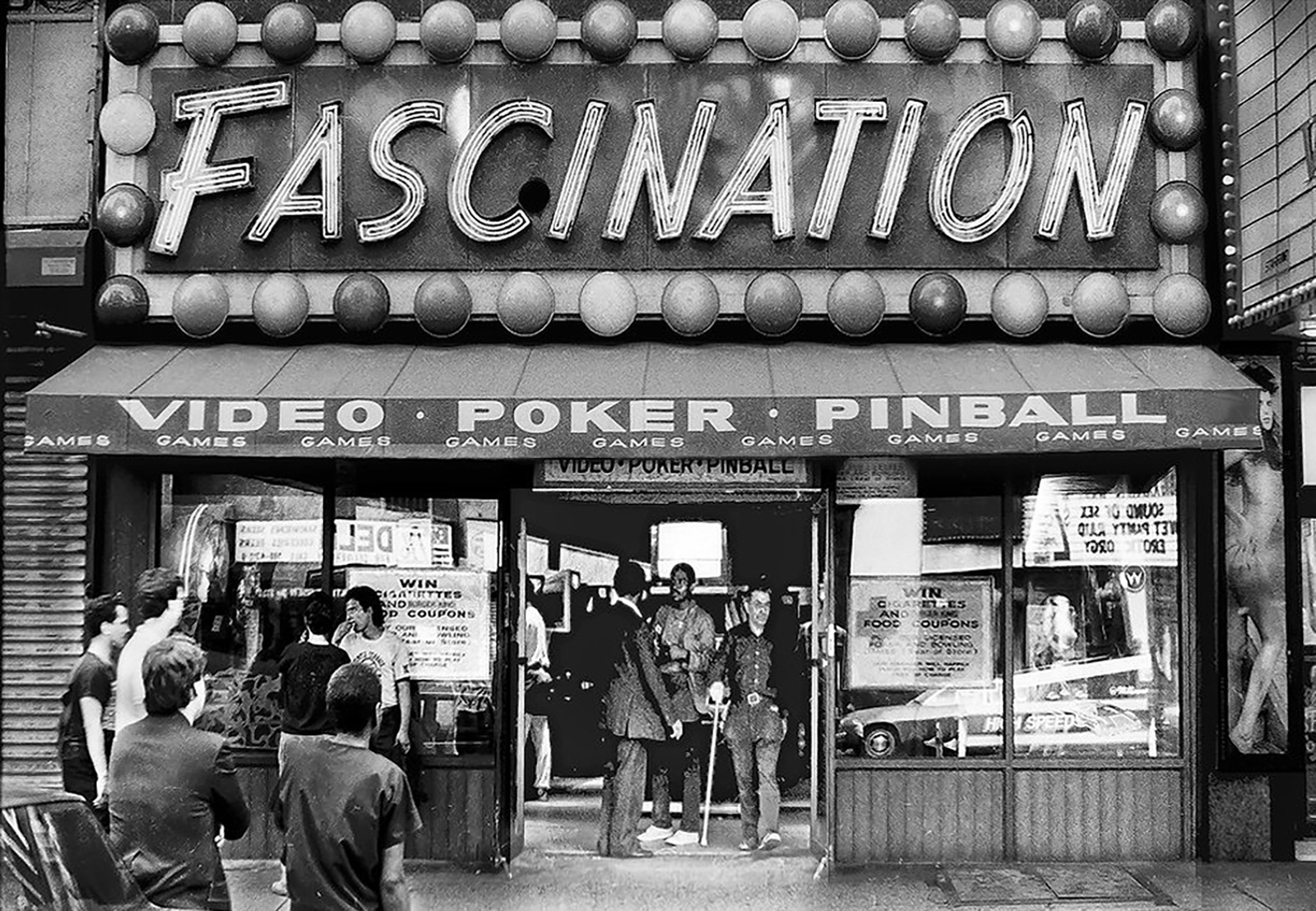

When I first studied this scene, I assumed it took place at a Playland — a popular chain of arcades found mostly in the Times Square area. But my opinion changed once I noticed in one of the shots a backwards neon sign that, when reversed, clearly spelled out, “Faber’s” — another NYC arcade chain whose flagship “Faber’s Fascination” was in Brooklyn’s Coney Island.

I thought it seemed unlikely production went all the way down to Coney Island to film one brief scene, so I checked to see if Faber’s had any locations in Manhattan, and asked Blakeslee to do some digging himself.

I found one article that indicated that Faber’s had arcades in Coney Island, the Rockaways, Long Beach, and Times Square in the 1930s. But as far as I could tell, there wasn’t a”Faber’s Fascination” in Times Square in 1980. There were a couple plain “Fascination” arcades in the area, but they weren’t associated with Faber. It appears as though Fascination was a reference to an old redemption game that eventually became a generic term for game parlors.

There was one Fascination at the north end of Times Square that was a popular hangout in the seventies and eighties, and was briefly featured in the opening minutes of Taxi Driver (1976). But it was not the place used in Arthur.

It was during this era that Fascination and dozens of other shops in Times Square were subjected to summonses by the police for violating an antiquated “Sabbath Law” — selling nonessential items on a Sunday. The law was finally voided in 1976 after 320 years of existence, being deemed unconstitutional by New York State’s highest court.

Once Blakeslee and I were certain that the Fascination on Broadway wasn’t part of Faber’s, we rechecked the scene to see if there were any other clues as to its location.

Blakeslee briefly focused on the pink neon below the Faber’s sign that began with “RE,” hoping it might be part of the arcade name. But it ended up not helping us with our search.

The one thing I focused on was what appeared to be a couple large, pulled-down gates in the background. My guess was they filmed the scene early in the day before the arcade was open, but since the “date” was taking place at night, they had to pull those metal gates down to block the sunlight. (Also explains why the neon was backwards and seemingly pointing at a wall; if the gates were up, the sign would be pointing out and onto the street.)

As I studied those pulled-down gates, I tried to visualized what the front of the arcade looked like and then suddenly, I realized there was no traditional door there. Instead, it looked as though the arcade had large “open-air” entrances, like what you’d find in a beachfront area. That made me think that they did, in fact, film the scene down in Coney Island.

Once I dropped this theory on Blakeslee, he used his superhuman internet-searching powers to almost immediately unearth a vintage photo of Faber’s in Coney Island that showed the very same neon signage from the movie.

It even showed the same large fan that was next to it, completely convincing us that we found the right place.

The photo also showed us that the pink RE was part of the phrase, BING-O-RENO, which was a type of pinball machine popular in the mid-20th century.

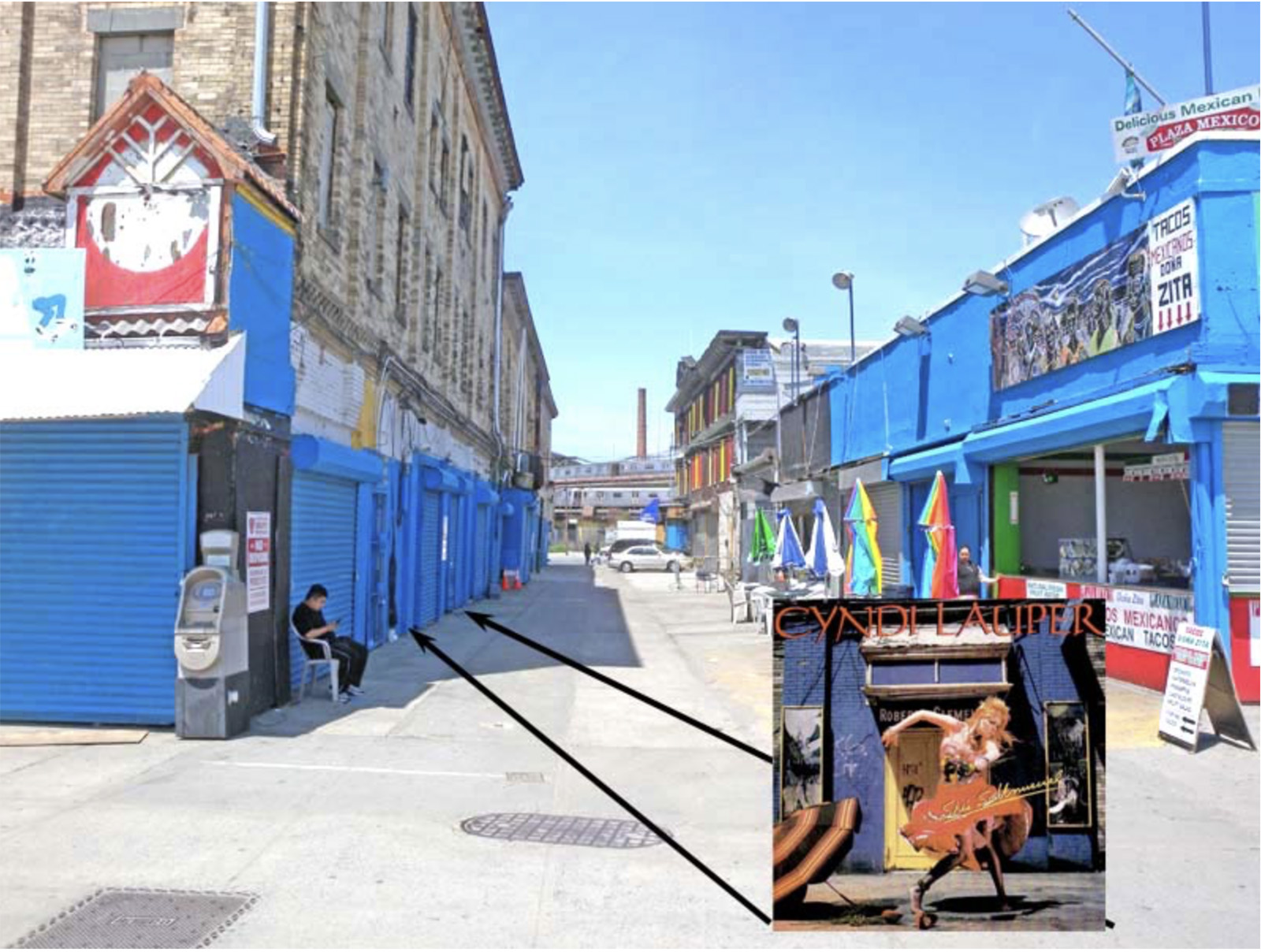

So, the characters were in the Sportland section of Faber’s which occupied the majority of the ground floor of the historic Henderson Building on Surf Avenue.

The Sportland section closed down some time ago, but to my surprise, the Fascination side lasted all the way until 2010.

The beloved arcade was finally forced to close when the new property owners, Thor Equities, made preparations to demolish the building. As might be expected, several historians and Coney Island preservationists opposed the destruction of the historic building.

They pointed out that Henderson’s Music Hall was an important Coney Island entertainment venue during its day and had featured a variety of music and vaudeville acts, including Al Jolson and the Marx Brothers.

Sixty odd years later, the back of the building would play a small role in eighties music culture when it was featured on the cover of Cyndi Lauper’s debut album, She’s So Unusual, which included her breakout song, Girls Just Wanna Have Fun.

This bit of trivia was discovered by PopSpots creator, Bob Egan, who seeks out the locations of album covers and other pop culture events in NYC.

Despite objections by locals, Thor Equities went ahead with their plans to raze the century-old building, claiming it was structurally unsound. Shortly thereafter, Faber’s large letters that blazed the night sky for decades were removed piece-by-piece, including the ones on the previously obstructed Sportland sign.

The removal was overseen by Carl Muraco, owner of Faber’s at the time, who hoped to sell the dismantled signs as well as the arcade machines.

That was back in September of 2010 and I can’t find any info on the fate of those Coney Island artifacts, but hopefully they didn’t end up in some scrap pile somewhere.

Today, the new one-story building houses several businesses, and the spot where Faber’s Sportland used to be is now a large candy shop called “It’s Sugar.” But there’s nothing sweet about the loss of that old building.

Martha Gives Arthur an Ultimatum

The exterior of Arthur’s grandmother’s opulent mansion has long been established as being the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum on E 91st Street. The Georgian Revival mansion (completed in 1902 for industrialist Andrew Carnegie and his family) has been featured in several other movies, including Marathon Man (1976), Jumping Jack Flash (1986) and Working Girl (1988).

While the exterior is unquestionably the Cooper Hewitt, I’m not sure where the interior was filmed. I couldn’t match it up with any of the rooms in the museum, so I suspect that it was filmed somewhere else — perhaps it was even a set.

Of course, there were no real puzzlers in figuring out where the following driving scene took place. It was clearly on the FDR, I just had to figure out what parts by looking at the distant buildings and such. As you can see from the “then/now” image above, the Queens skyline across the river has changed dramatically over the years — becoming much taller and denser than it was in the 1980s (or even the 2000s for that matter).

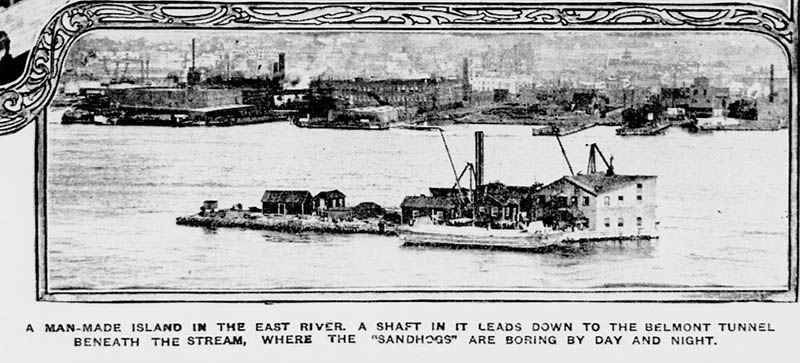

The one constant that helped me nail the exact strip of road he was on was Belmont Island in the East River. Measuring a modest 100×200 feet, Belmont is an artificial islet that was created in 1906 during the construction of the Steinway Tunnel (located directly underneath it and used today by the IRT’s 7-train).

Belmont is officially the smallest island in Manhattan and is currently protected by New York State as a sanctuary for migrating birds, including a small colony of double-crested cormorants.

While not open to the public, a group of employees from the United Nations who were followers of the guru Sri Chinmoy, were allowed to lease the island in the seventies to plant and maintain flora. (The island is unofficially named after a friend of Chinmoy, Burmese diplomat U Thant.) Their lease ended in the nineties, but they weren’t the only folks who occupied the island over the years

In 1972, activists took over the land for two and a half hours in protest of USSR Chairman Leonid Brezhnev’s speech at the UN that would announce an exorbitant tax on Soviet Jews who wished to emigrate to Israel. Then in 2004, artist Duke Riley surreptitiously rowed onto Belmont Island under the cover of night and proclaimed it a sovereign nation in objection to the Republican National Convention being in NYC. This temporary seizure was marked by his hoisting of a 21-foot-long pennant depicting two electric eels from the island’s navigation tower.

As far as I can tell, no one has since occupied the islet, but you can get a decent view of it by taking the Astoria-bound NYC Ferry up the river.

The Johnsons Estate

I knew for a long time that they shot the exterior of the Johnson estate at NYIT de Seversky Mansion on Long Island, but it wasn’t until recently that I confirmed the interiors were shot there, too. After discovering an amateur iPhone video of the inside, I determined they shot in the mansions’s front foyer and the small, wood-paneled sitting room just to the left of it.

Situated on the island’s North Shore (known for having some of the most opulent estates in the country), de Seversky Mansion was originally called White Eagle when it was built between 1916 and 1918 for the second wife of businessman, Alfred I du Pont.

Designed in the Georgian Revival style, with a red brick façade and white marble embellishments, the residence was sold shortly after its completion to du Pont’s neighbor Howard Phipps who later passed it on to his sister and her husband, British politician Frederick Guest. The home remained with the Guest family until it was purchased by the New York Institute of Technology in 1972. The mansion was then renamed after Russian aviator, Alexander P. de Seversky, who was a member of the school’s Board of Trustees and instrumental in acquiring the property.

Today, de Seversky Mansion remains a part of the Old Westbury campus of NYIT and is often used for school and private events. In fact, it was Dana and Nicolette from the NYIT de Seversky Mansion Sales & Events team who kindly allowed me to visit the estate and take some modern pictures.

I’m glad I was finally able to visit and photograph the estate earlier this year. I first tried photographing it in 2021, back when I was only aware that the mansion’s exterior was used in Arthur. I had borrowed my aunt’s car and traveled to Brookville to take some pictures of the facade, but this was still in the midst of the pandemic and access to the campus was limited to students and faculty.

I tried to get access to the mansion via the residential Dupont Court, but the connecting road was gated off, so I decided to move on to other movie locations on Long Island (namely, the jail used in Three Days of the Condor, which was a rather stark change of scenery).

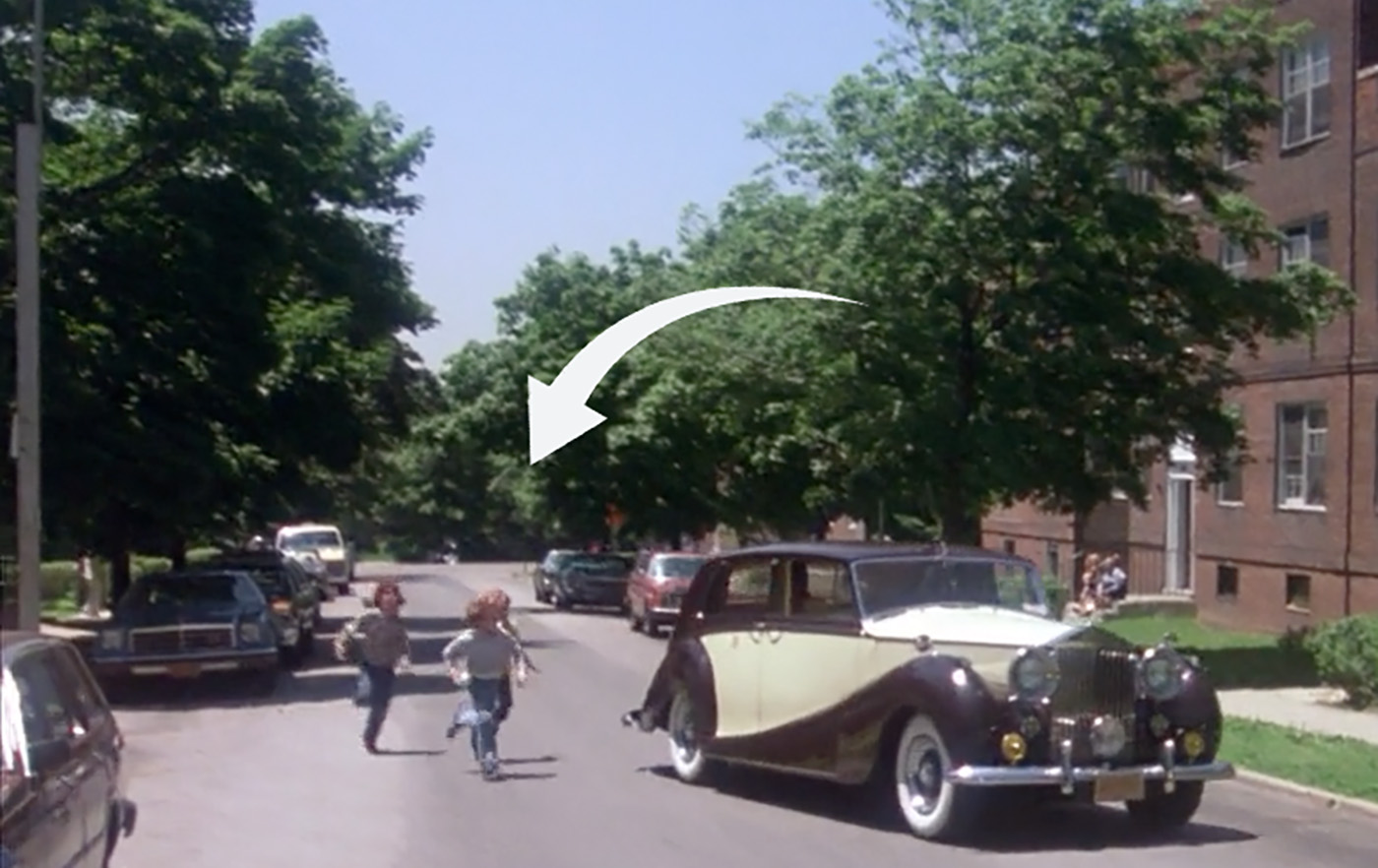

Arthur Visits Linda

Racetrack

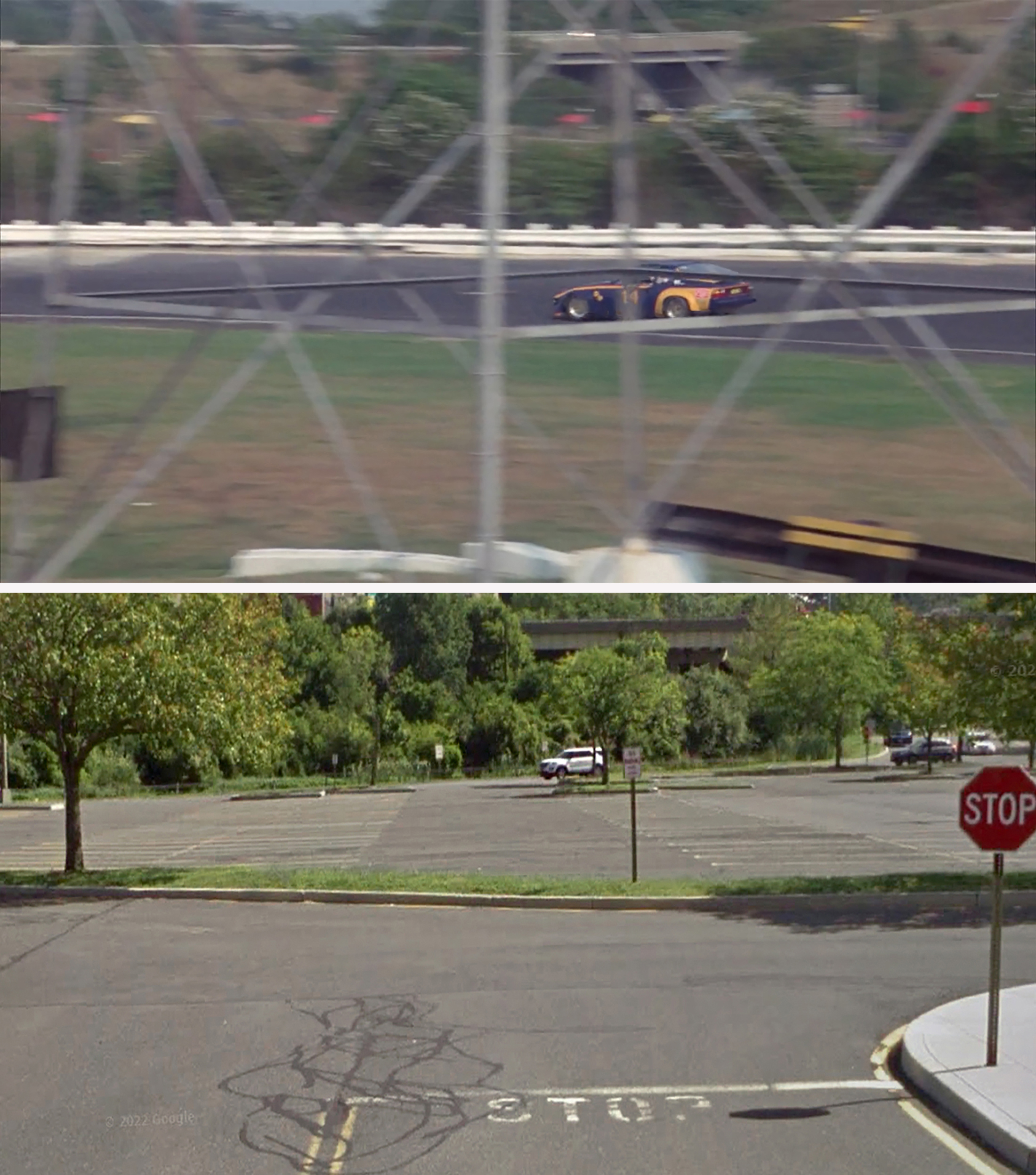

Filmed at the old Racearena in Danbury, CT, I was able to figure out the general orientation of this scene by finding an old satellite image of the area and lining it up with a modern view. The calculations were confirmed by matching up the large hills and elevated highway in the background.

But I probably would’ve had a difficult time knowing where this scene took place at all if it hadn’t been published in a few car-enthusiast websites. Apparently the old Danbury Racearena holds a fond place in the hearts of old race fans, and several recognized that Arthur filmed a scene there.

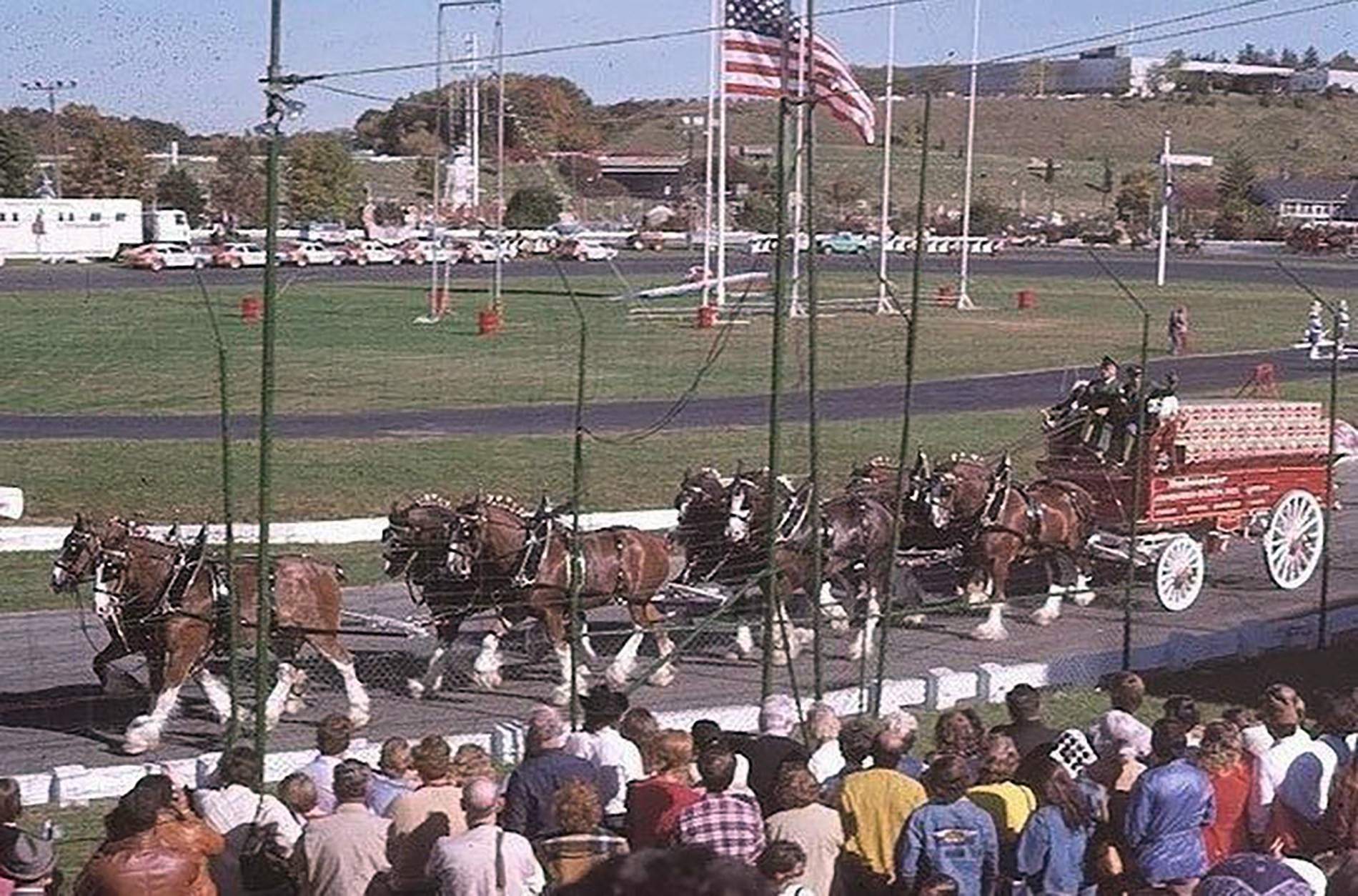

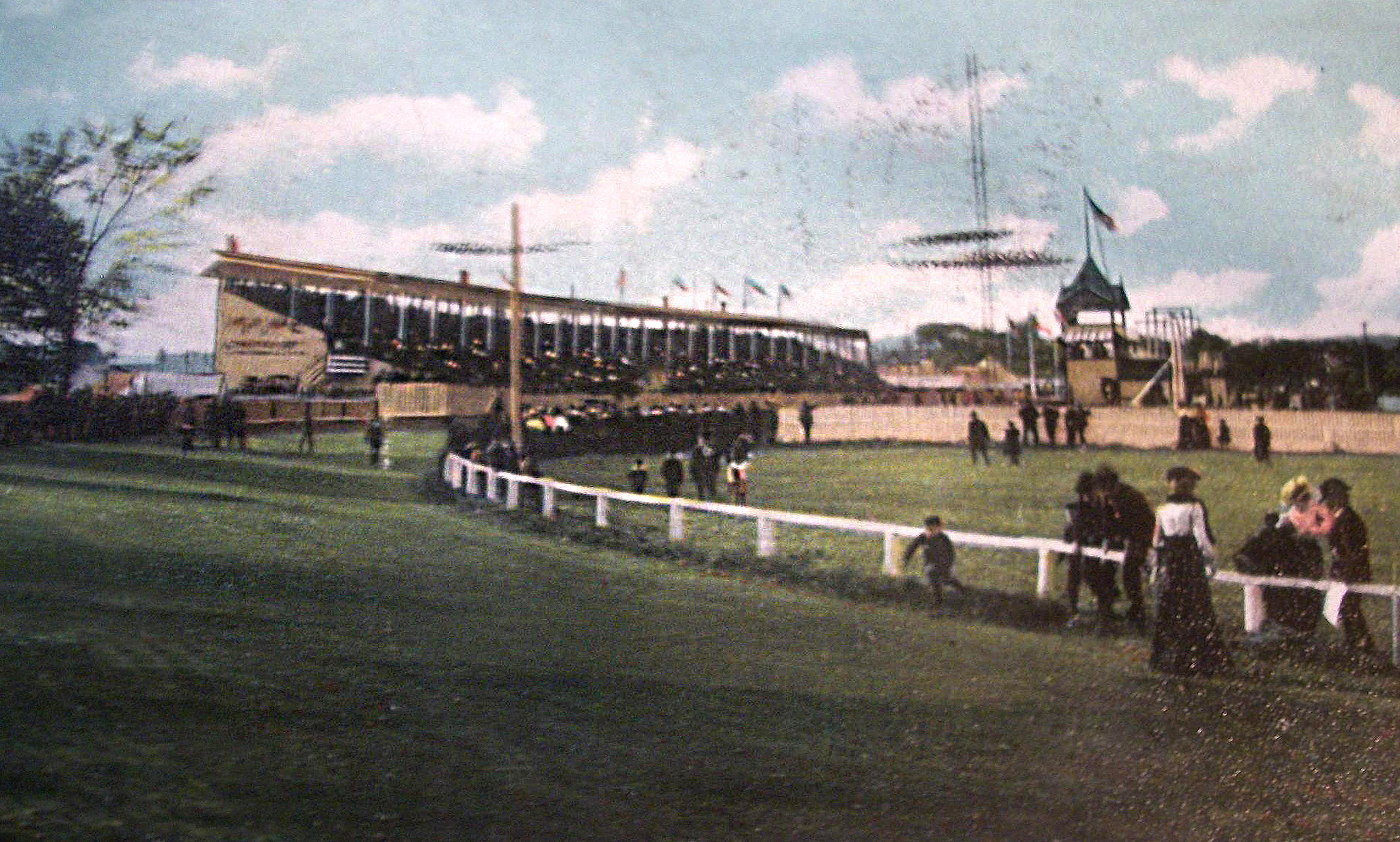

Located on the Danbury Fairgrounds in Danbury, Connecticut, the track was originally used for horse racing when it opened in 1869.

It eventually evolved to a 1/3 mile paved track to be used by race cars. At this point, the track was already an integral part of the state fair’s activities, hosting a variety of shows and events. It was also the place where the daily parade would culminate, showcasing an endless line of bands, floats, clowns and exotic animals in front of a packed grandstand.

Of course, racing was the main purpose of the fair’s Racearena, and it hosted all different kinds — motorcycles, speedboats, stock cars, midget autos, and even ostriches took a turn at competing.

In addition to October’s “Fair Week,” conventional competitive auto racing would be held at the Racearena every Saturday night throughout the summer. And this tradition continued up until the year Arthur came out.

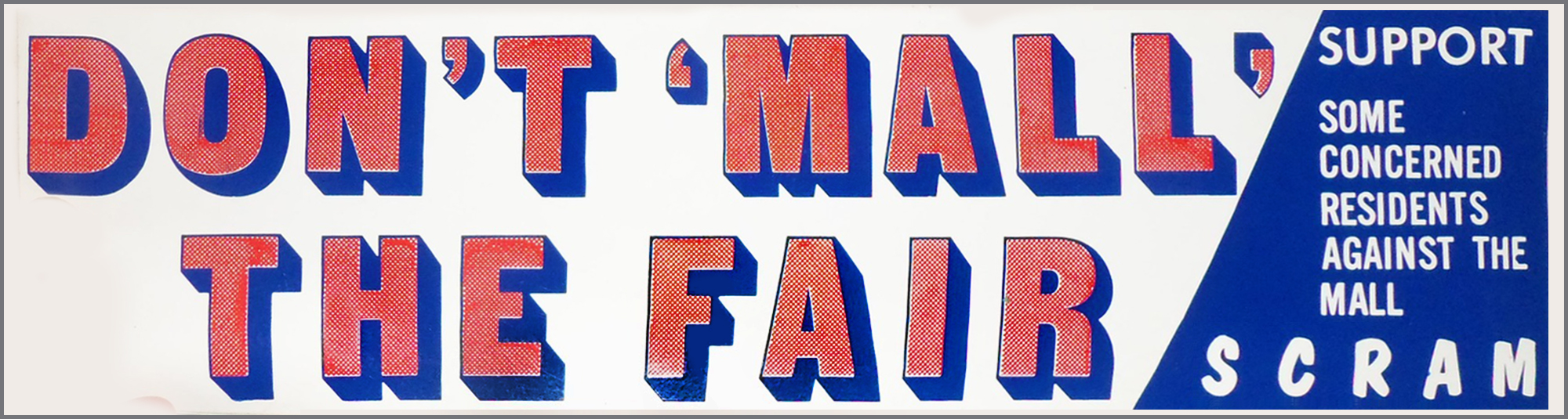

At the end of 1981’s fair week (which saw an estimated 400,000 attendees that year), the grounds were permanently closed and the land was bought by a real estate developer. A few years later, the “Danbury Fair” shopping mall went up in its place.

Naturally, many locals, in particular race fans, protested this development, but it mostly fell onto deaf ears. (Accusations were made that then-mayor of Danbury, James Dyer, took $60,000 in bribes to ensure the sealing of the deal, but the charges were eventually dropped.)

The new shopping center opened in 1986 and is still considered one of the more successful of its kind in the state.

However, like most malls in the United States, the volume of customers has been slowly diminishing, and there is currently some interest in converting some empty retail space into an apartment complex (specifically, where Lord & Taylor used to be).

It’s all part of the mall’s plans to reimagine itself as a “24-hour environment,” which would also include the addition of some green space around the perimeter.

As of this writing, these development plans are still up in the air, but if they go through, I’d definitely be curious to see what an apartment attached to a Bath & Body Works will go for in rent.

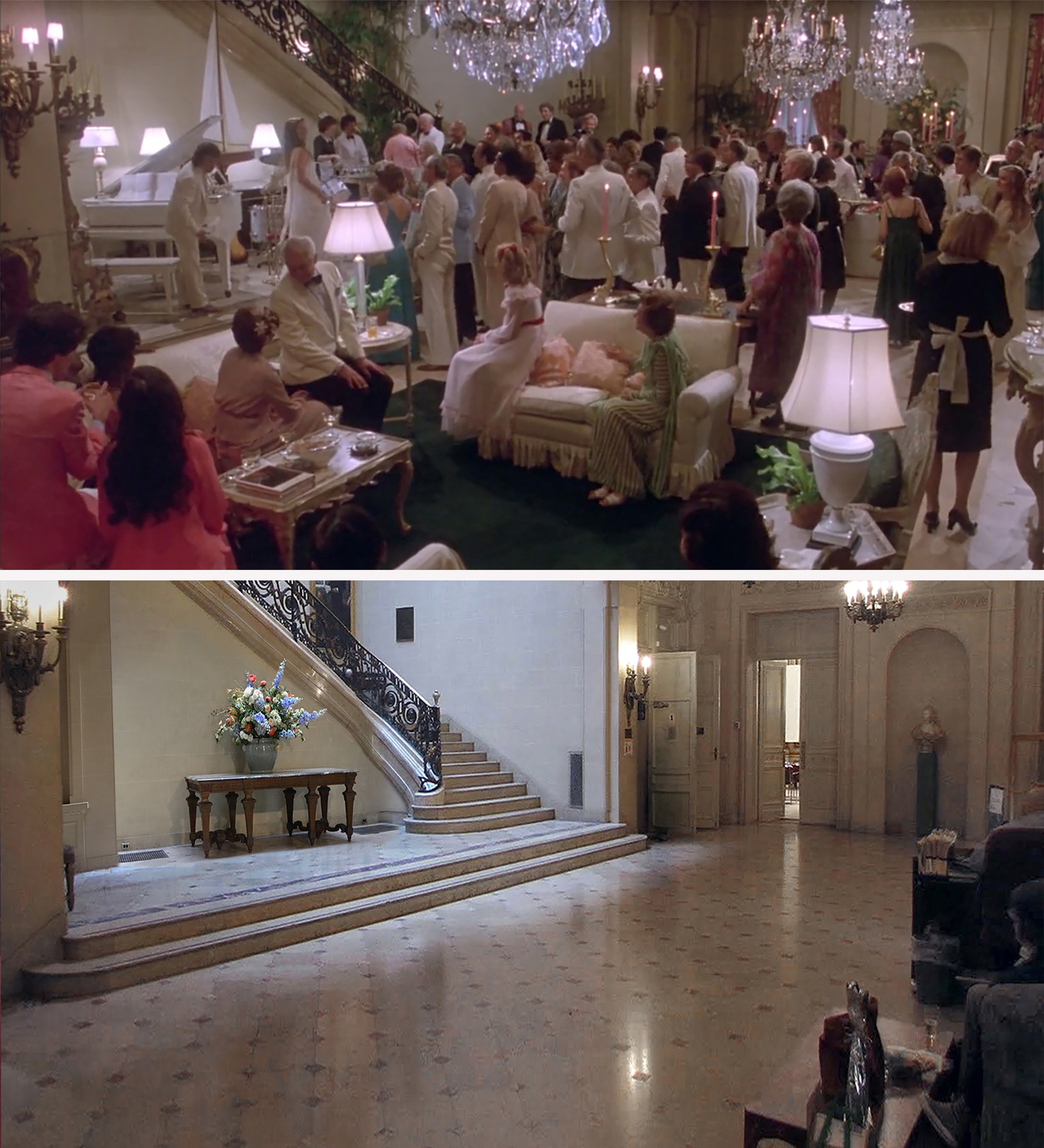

Engagement Party

Both of these locations were listed on IMDB’s production page, but neither entry indicated what scenes were filmed there. I was quickly able to determine that the Marshall Field House at Caumsett State Park was the exterior of Arthur’s father’s estate, but it took me a while to connect the James B. Duke House on E 78th Street with the interior. I always just assumed production used the inside of the Marshall Field House, but once I saw what it looks like inside, I knew it wasn’t a match.

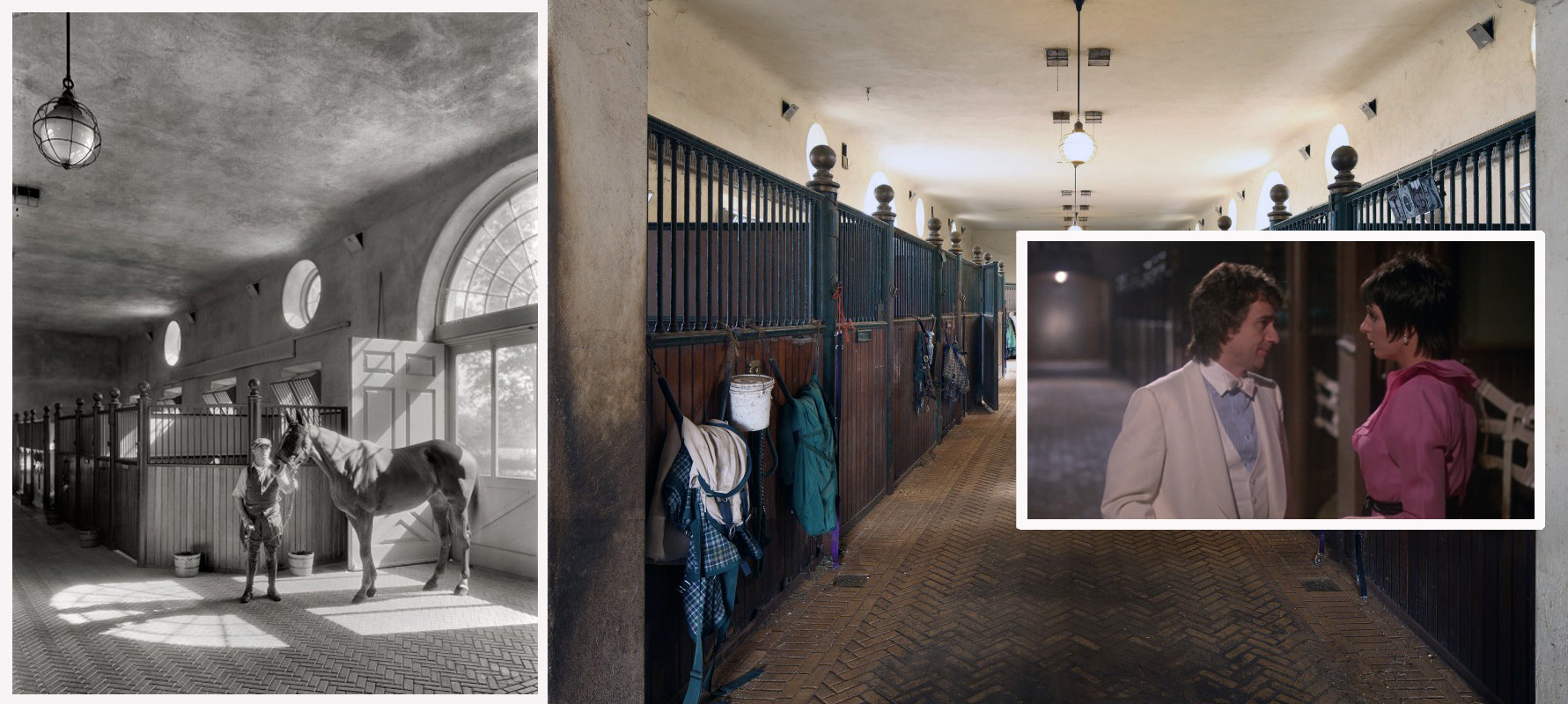

But they did end up using one interior at Caumsett State Park for the scene where Arthur and Linda go to the horse stables in the middle of the party. This was filmed inside the historic Polo Stable, currently leased by Lloyd Harbor Equestrian Center, which is privately run and not open to the general public.

When it came to the party interiors, I was surprised production used a Manhattan location, opposed to using one of the mansions on Long Island.

Although, perhaps it was logistically easier to film in the city. Plus, the fact the James B. Duke House is owned and operated by a university, the price for leasing out the space might’ve been reasonably affordable.

While a part of NYU today, the palatial limestone mansion was originally built for the recently-married tobacco magnate, James Buchanan Duke. The home was constructed between 1909 and 1912 on the coveted easterly side of Central Park, often referred to as the “Boulevard of Rank.” Its elegant design was heavily inspired by the 18th century Château Labottière in Bordeaux, France (although some contemporaneous critics called it a flat-out rip-off).

Like the Bachs in the movie Arthur, the Dukes were known for holding lavish parties in their NYC home. But it wasn’t even their main residence. Across the river in Somerville, NJ was a 2,500-acre country estate which was listed as their primary residence.

Just over a decade after the 78th Street mansion was completed, James Duke contracted pneumonia and died in his bedroom. This left the status of the estate in limbo for a couple years.

Due to the abstruse wording in his will, James Duke’s NYC house became part of a legal predicament for his family, where it was unclear who was the rightful owner of the property. It essentially ended with his teenage daughter, Doris, filing a “friendly suit” against her mother, Nanaline, in order to gain the vast real estate holdings. It also prevented the house from being put up for auction.

Upon receiving the NYC residence and its contents in 1927 (which also included a collection of tapestries, four automobiles and a private railroad car), fourteen-year-old Doris Duke became known as “the richest girl in the world.” By the time her inheritance was fully realized on her 21st birthday, her fortune was increased by about $30 million. And as her net worth grew, so did the public interest in her, often resulting in throngs of journalists crowding her 78th Street home.

By the late 1940s, the house (which Doris had jocularly nicknamed “the rock pile”) was primarily used by her mother, Nanaline. Then in 1958, it was announced that the two Duke women would be donating their Upper East Side mansion to New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts. This extravagant gift allowed the institute to more than double its space from 19,000 square feet at their old location on E 80th Street, to 40,000 square feet at the Duke House.

Since then, the Institute’s effort to carefully renovate and maintain the home has kept the James B Duke House a delightful beacon in a neighborhood dominated by towering apartment complexes.

Linda’s Diner

This diner location has been widely identified amongst movie publications, but I first discovered it in a 2011 article in The New York Post. (It might be noted that the article was being written in advance of the release of the pointless remake starring Russell Brand, which I worked on for one day as a background actor.)

The Lenox Hill Grill ended up being one of the very first NYC locations I sought out and photographed since starting this project, having visited the eatery in early 2017. You can tell that it was the early days of internet-movie-location-sleuthing because the owner was genuinely surprised someone had discovered the Grill’s place in movie history. He was also impressed that I brought along stills from the movie to compare with the real-life space.

The Lenox Hill Grill ended up being one of the very first NYC locations I sought out and photographed since starting this project, having visited the eatery in early 2017. You can tell that it was the early days of internet-movie-location-sleuthing because the owner was genuinely surprised someone had discovered the Grill’s place in movie history. He was also impressed that I brought along stills from the movie to compare with the real-life space.

The affable middle-aged fellow (whose name unfortunately escapes me some seven years later) filled me in with a little history of the Grill and the adjacent pizza shop which his family had owned for nearly sixty years. He told me that most of the restaurant workers who appeared in the movie were his family members who were basically “playing themselves.” In particular, I remember the owner pointed out that the man by the entrance in the second “then/now” image above was his late uncle.

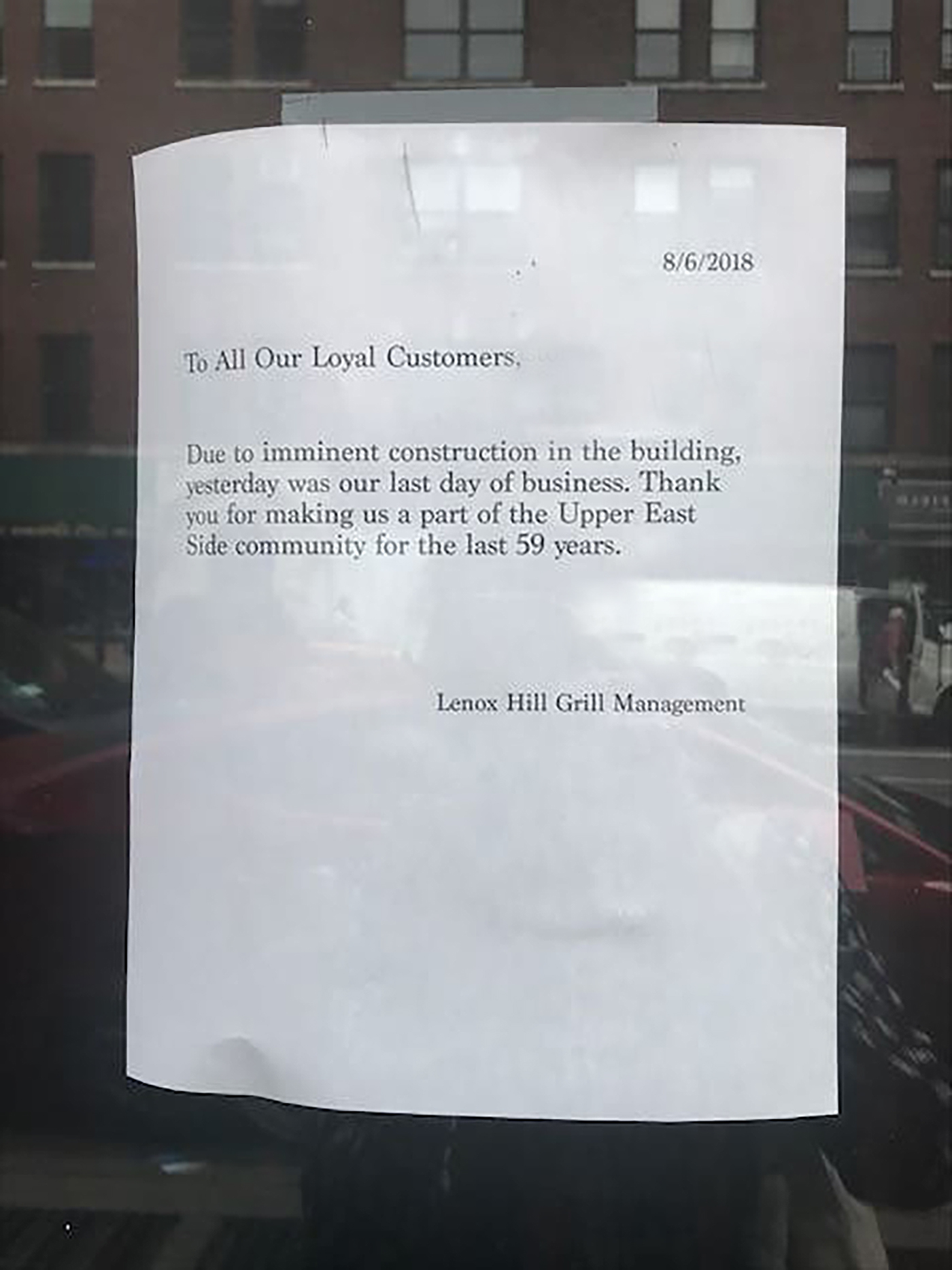

It’s a good thing I went the Lenox Hill Grill when I did, because the restaurant ended up closing its doors one year later due to the landlord deciding to reconstruct and expand the building.

I had no idea this happened until I stumbled upon a shuttered front while exploring the area one afternoon. I was saddened for the loss of another mom-and-pop business, but also disappointed I wasn’t able to take a few better modern pictures. (Admittedly, the ones I took in 2017 were a bit dark and sloppy.)

When I visited the site earlier this year, the building reconstruction was nearly complete. So, whenever a new business opens up on the ground floor, I’ll make sure to pay them a visit and snap a few pics.

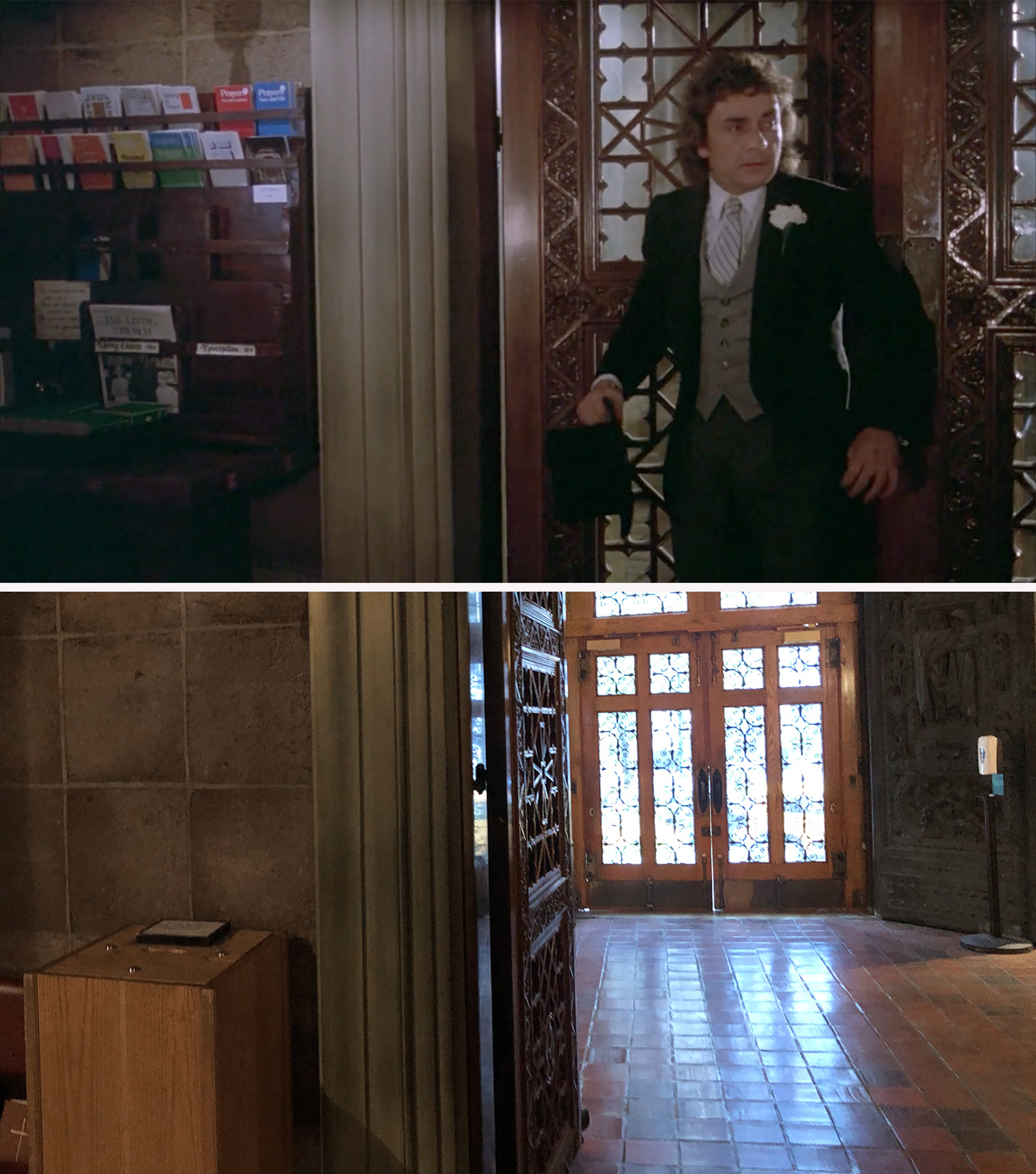

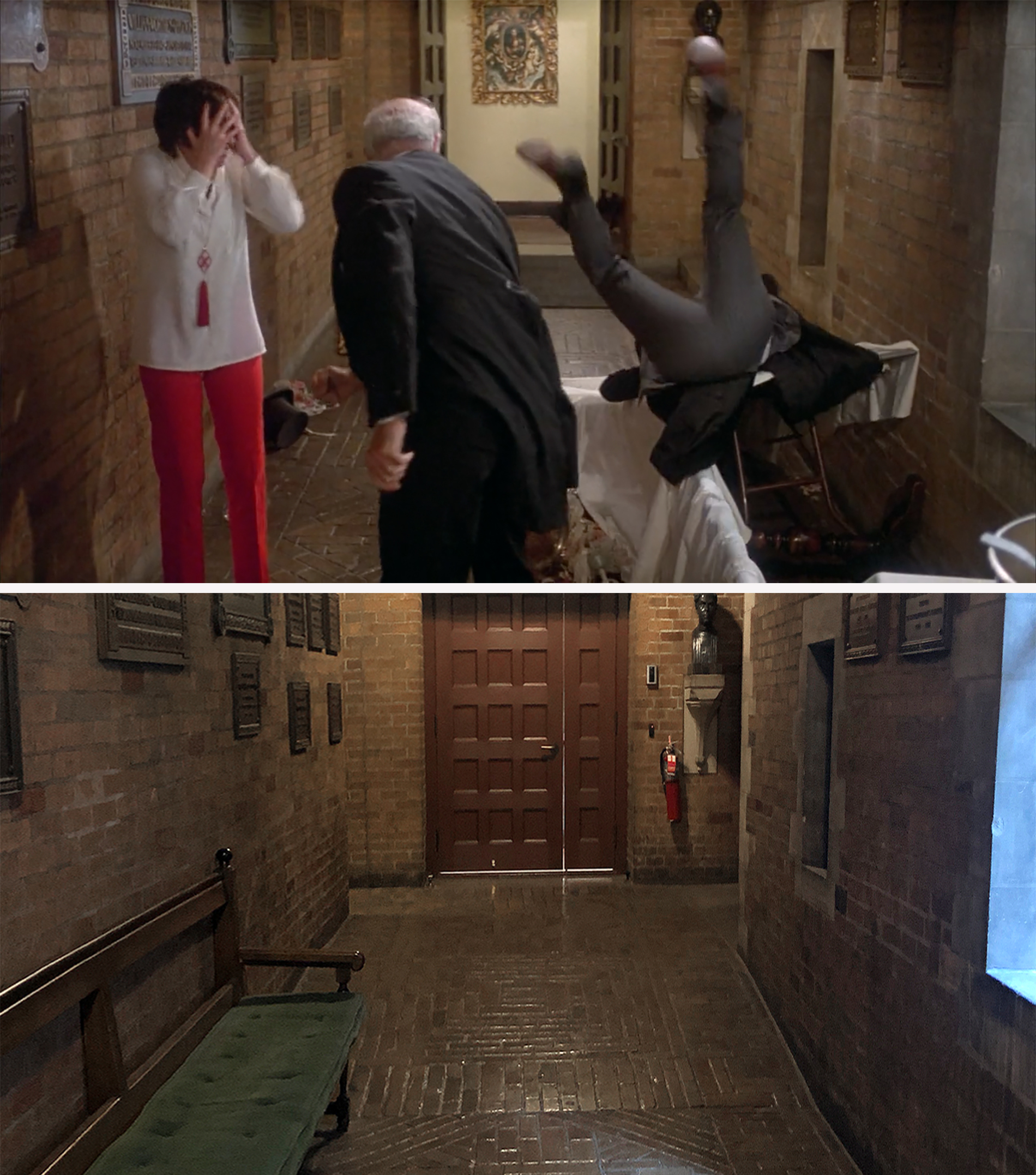

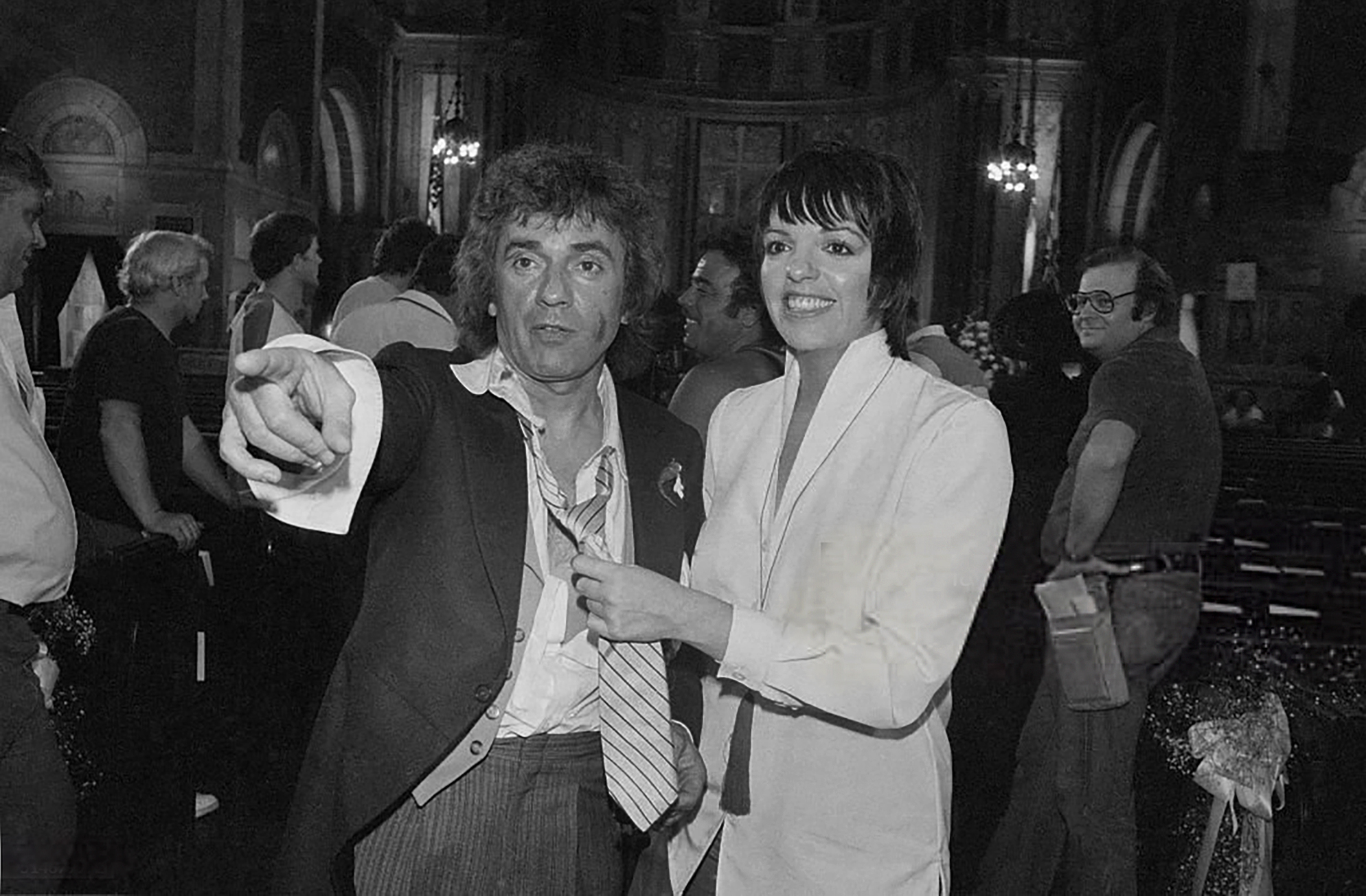

The Big Wedding

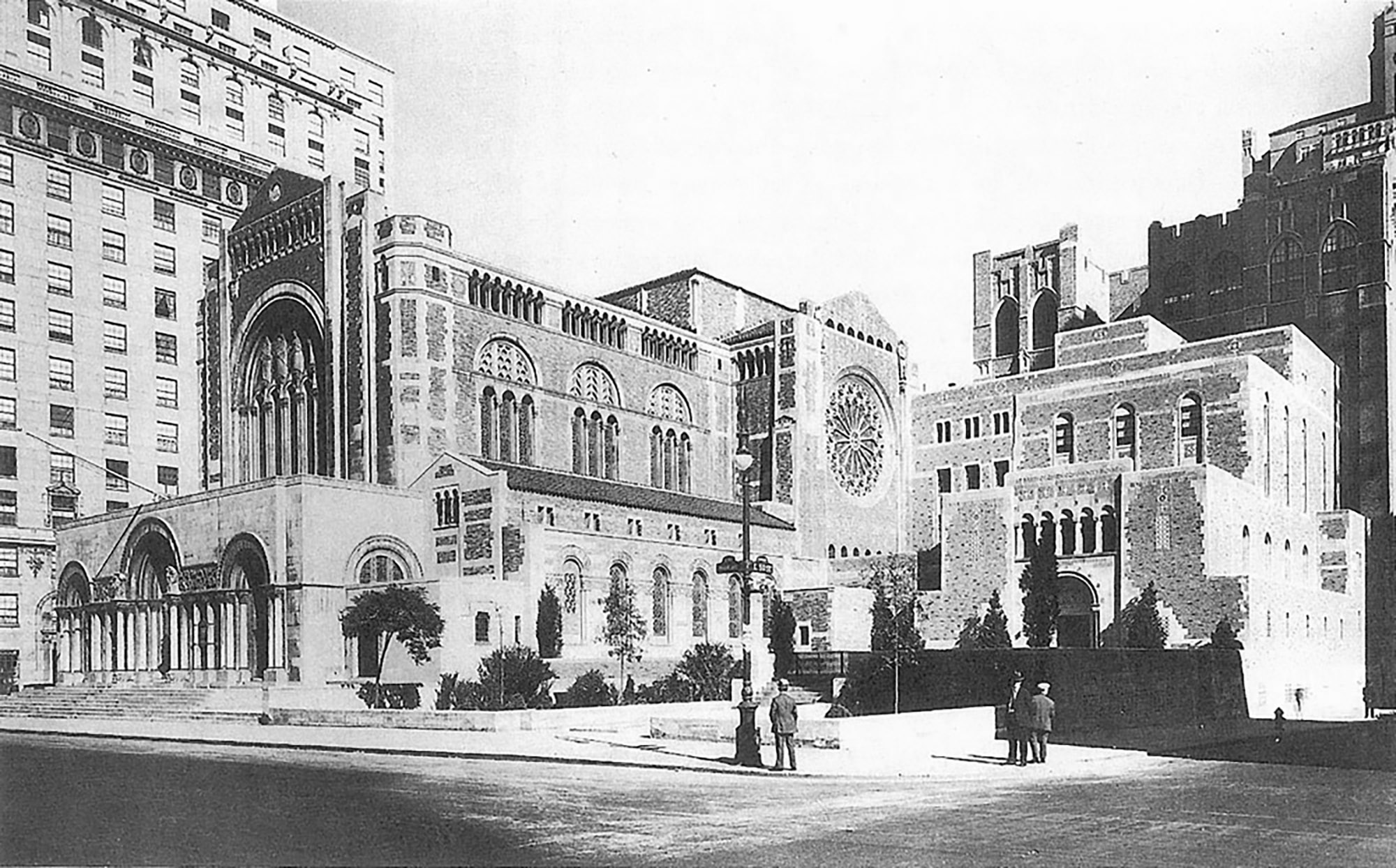

The movie ends at the eminent St. Bart’s, a historic Episcopal parish located on the east side of Park Avenue in bustling Midtown Manhattan. Established on that lot over 100 years ago, the church has been featured in several films and TV shows., but I believe Arthur was the first to immortalize it on film (if you don’t include a brief appearance of its dome in 1978’s Superman: The Movie where the red-caped superhero zips over it).

The church was erected in 1916–17, but it was a simplified design, and it would be over a decade before the interior was fully completed and the iconic Byzantine dome was added to the roofline. Around the time those updates were being made, they also installed a new 1,825-pipe Skinner organ, making it the largest in New York.

While St. Bart’s is a standout landmark on Park Avenue, its footprint was in danger of being altered just as Arthur was getting ready to be released.

A battle within the parish was brewing over a real estate developer’s offer to purchase the site of the adjacent community house to make way for an office tower. Different leaders from the church had opposing views of this prospect, and the conflict spilled into the city’s designated landmark status of the building. It eventually became a heated legal battle that worked its way up to the Supreme Court, which in 1991, declined to hear an appeal on the matter, essentially upholding the Second Circuit’s decision to deny the demolition of the community house.

It was this decision that makes St. Bart’s an unusual sight in NYC, especially in the compact Midtown Manhattan — a church with a large swath of open air space.

Unlike some other comedies of the 1980s, Arthur has virtually disappeared from the movie history lexicon. While not a perfect film, it is unquestionably Dudley Moore’s greatest role, and the chemistry between him and John Gielgud is some of the best you’ll ever see.

While the casting of Liza Minnelli as a poor waitress from Queens seems a bit far-fetched, she does a serviceable job as Arthur’s love interest, displaying lots of vim and vigor.

We also get some great performances from the second-tier cast, including Stephen Elliott as the menacing Burt Johnson (who would later play the uptight chief of police in 1984’s Beverly Hills Cop), Barney Martin as Linda’s out-of-work father (probably best known for playing Jerry’s dad on the TV series, Seinfeld), Ted Ross as the sympathetic driver, Bitterman, and probably my favorite of the group, Geraldine Fitzgerald as the cutthroat matriarch of the Bach family.

And kudos to writer-director Steve Gordon for having an English comedian taking on the lead role, despite the studio’s push to cast John Belushi. While having the SNL alum would’ve made an interesting comedy, I don’t think it would have had as much depth and pathos as what we ultimately got.

Sadly, Gordon died from a heart attack one year after this movie came out, at the age of 44. This was his only feature film, and it’s a shame we’ll never know what a sophomore effort would’ve produced.

I also admire that the entire film was shot on the east coast. It might’ve been because it was essentially a minor, lower-budget production and under the studio’s radar. But I think it was mostly because it was financed by Orion Pictures, who already had a track record of allowing Woody Allen to shoot all of his own stuff in New York.

I’m quite happy that I was able to track down and photograph nearly all the locations, including several interiors. Aside from the inside of Martha’s mansion, the only other location that remains a bit of a mystery is the hospital where Hobson is admitted. Some sources claim it was filmed in Lenox Hill Hospital on E 77th Street, but I haven’t found any new or vintage images that match what appeared in the movie.

I think it’s possible they filmed the hallway scenes at the actual Upper East Side hospital, but the room was most likely a set back at Kaufman Studios.

Regardless, I think we were able to do a pretty thorough investigation into these filming locations, considering the surprisingly minimal amount of behind-the-scenes information out there. I suppose if I had Arthur’s 750 million dollars, I could’ve spent some of it on a more in-depth investigation. Hell, if I had Arthur’s bankroll, I’d even spend some of it on researching the depressingly awful 1987 sequel, Arthur 2: On the Rocks.

inspiring!

LikeLike

Why didn’t you try to find where the bar scene was filmed. I always thought that was one of the best scenes in the movie! The guy who plays the drunk talking to Arthur was classic

Jim

LikeLike