Allan Dwan’s exceptional silent melodrama, which was adapted from a bestselling novel of the same name, was one of the last major feature films to be shot at Fox’s Studios in New York. The story is about a young man named John Breen (George O’Brien), who loses his mother and step-father in an East River barge accident, and is taken in by a Jewish couple on the Lower East Side. John soon begins to fall in love with their daughter, Becka (Virginia Valli), and becomes a celebrated prizefighter, capturing the attention of a rich benefactor, who is secretly his real father.

The incredibly prolific Dwan (who estimated that he directed 1,850 films during his career) was lauded as a pioneer of the early cinema and had a knack for getting realistic performances from his actors. One way he achieved this was by filming on-location whenever possible, taking advantage of the authentic surroundings. However, while East Side, West Side was shot entirely in New York City, the number of real locations are somewhat minimal, but enough to give a sense of what the city was like in the 1920s.

New York Skyline

Figuring out what part of Manhattan is being shown in wide skyline shots is usually pretty easy since you have big, obvious landmarks to work from. And with the Brooklyn Bridge in the foreground, I was able to instantly identify these opening shots from the film.

Getting the correct perspective for the “before/after” images was easy as well, since it was clear they were originally taken from the neighboring Manhattan Bridge just to the north.

Living on a Barge

Like the opening shot of the Brooklyn Bridge, it was fairly easy to figure out the location of this scene on the family barge. Judging by the shot looking north at the Brooklyn Bridge, I could tell we were somewhere near the southern end of the East River, and I used the positioning of the Manhattan buildings to get a better idea of where exactly.

Of course, one problem is that the skyline has changed a lot since 1927, and even when it comes to extant buildings, they’re hard to spot since a lot of them are obscured by newer, bulkier skyscrapers. One way around that is viewing the skyline in 3D mode on Google Maps, which allows you to look at things from different heights and angles.

What’s nice is in the last “before/after” image above, you can still see a lot of the same buildings that appeared in this scene, since Battery Park affords an open, unobstructed view. Another interesting thing is that you can get a sense of how much wider the southern tip of Manhattan got after Battery Park City was added to the west side of it.

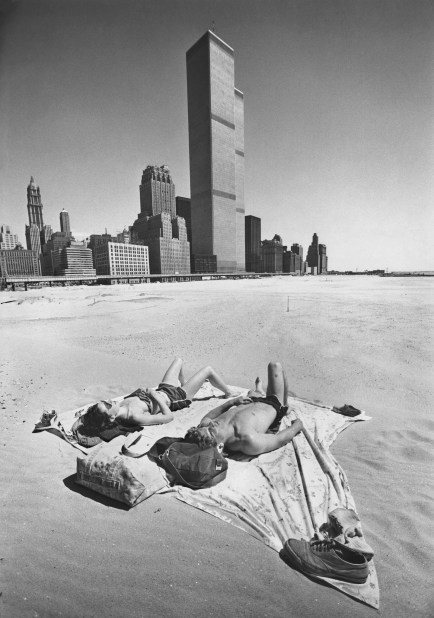

The idea of adding land to the Hudson River was first put forward by Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller in the 1960s, with a proposal to create a residential neighborhood in southern Manhattan from abandoned docklands. The original plans were so exuberant and convoluted, with various groups intending to use the land in different ways, it took years before everyone was on the same page.

Most of the southern half of Battery Park City was made up of landfill material taken from construction sites of the World Trade Center and other buildings in Lower Manhattan, while the northern half was mostly filled with sand dredged from nearby areas. By 1976, the landfill was complete, but due to the city’s fiscal problems, any significant construction didn’t begin until 1980 with the first tenants not moving in until 1985.

In that period between when sand started being added to the shoreline and when the neighborhood was fully developed in the 1990s, some New Yorkers used the primitive land as a makeshift beach.

Technically, the sand wasn’t intended for public use, with fences and barriers put up to discourage visitors. But, of course, many bold Manhattanites ignored these deterrents and used the land as a surreal stage to display large art projects or simply as a place to go sunbathing. That all ended in the 80s when the sand got paved over to create the modern, mostly-residential neighborhood that exists there today.

Dreaming of Skyscrapers

This was literally a four-second shot of a building superimposed onto a brick being held by the John Breen character, but I still wanted to identify it. Although, I almost immediately guessed that it was the New York Telephone Company Building (now called the Verizon Building) at 140 West Street, mostly because I had recently studied the location for another film shot in NYC — 1929’s Applause.

After confirming it was indeed the Telephone building, I was frustrated to see that it’s now surrounded by a cluster of huge skyscrapers (including One World Trade Center), making this historic structure barely visible today.

Begun in 1923 and completed the same year this film was being made, the 32-story skyscraper at 140 West Street was conceived as an answer to the swelling demand for telephone service in the city, creating a centralized location from which most operations could take place. The designer in charge was famed-architect, Ralph Thomas Walker, who was able to create a rather unique structure that could satisfy the technical requirements of a telephone company but still be aesthetically pleasing to the citizens of New York.

Some believe Walker’s monumental edifice was pivotal in setting a new course in modern urban architecture, being a quintessential example of what we now regard as Art Deco design.

The facade was simple and streamlined, making the most out of the mandated setbacks on the higher floors (a requirement made by the 1916 zoning ordinance in order to ensure light reached the street below). Walker also made sure the interior (most notably the lobby) stayed true to the modernistic theme of the building.

The lobby’s 22-foot-high ceilings were given painted murals depicting “Milestones of Communication,” and the walls and floor were made of black- and ochre-colored marble, adorned with ornate bronze fixtures. The Art Deco motif is even present in the chandeliers, which have setbacks similar to the exterior.

The ten floors immediately above the lobby served as central telephone offices, and were designed to handle the heavy equipment used by the company, supporting structural loads of up to 275 pounds per square foot. The New York Telephone Company Building also had an array of amenities, such as an auditorium, a gymnasium, a Mediterranean-styled cafeteria, and a full-scale training school where newly-hired switchboard operators went through a four-week training course.

Today, Verizon Communications operates out of the lower levels of the building, but everything above the 10th floor has now been converted into luxury condominium units.

When it comes to Art Deco buildings, people usually think of the more famous Chrysler, Empire State, and Rockefeller Center, but when the New York Telephone Company headquarters first graced the landscape of lower Manhattan, it was an immediate world-wide sensation. It’s no wonder it served as an inspiration for the John Breen character in this movie.

Arriving in Manhattan

My research partner, Jeff Blakeslee, was instrumental in helping me find this filming location, particularly the first part where the John Breen character falls off the carriage.

I first tried tackling this scene myself by focusing on the painted signs on the buildings in the background. I had trouble reading them, but it looked like the building on the right was for a paper manufacturer. I then went to the NY Public Library on 42nd Street to look through a 1927 Manhattan phone directory. But since I couldn’t clearly make out the name (not being able to tell if the first and third letters were Bs or Ds), I ended up with nothing.

However, Blakeslee is a master at deciphering blurry signs and storefronts, and figured it said, “Babino &” something. Then, after doing a basic internet search, he found a listing for a “Babino & Gatto, Inc.” at 177 South Street in the 1922 edition of Davison’s Textile Blue Book. From there, it was off to the NYPL digital collection to find some old photographs.

The first thing Blakeslee found was a photograph from the 1920s of 176-181 South Street which seemed to confirm we got the right address. While the Babino & Gatto paper maker signage was gone, the sign for Dominick Serrantino paper mill on the left building was still intact and seemed to match the film.

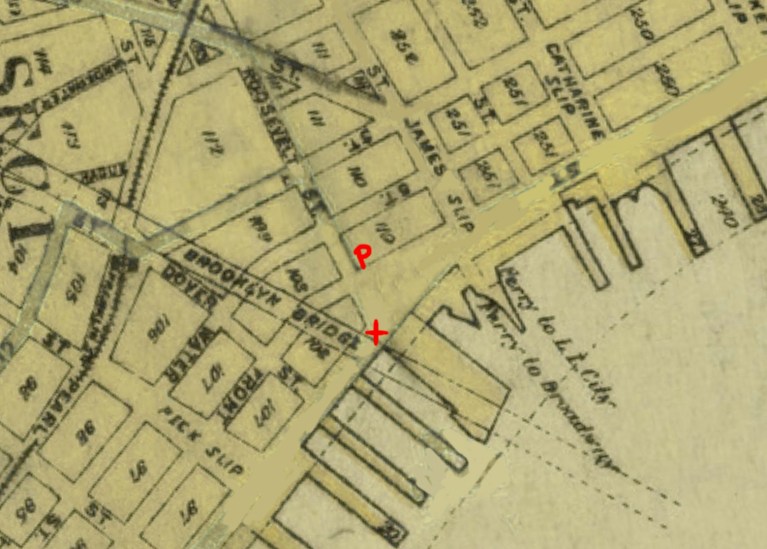

He then checked out an overview map of the area, where he could see that South Street had a slight shift in it, where the block of buildings on the left (where the Breen character is confronted by the Grogan Gang) was slightly closer to the river than the block of buildings on the right (with the paper companies). The map also showed that those buildings on the left were almost directly under the Brooklyn Bridge, near the Manhattan tower.

Knowing the basic overview of the area, it became easier to find photos of the buildings on the left. Or rather, find photos of where those buildings used to be, as it seems 173-174 South Street got razed shortly after this film was made. Unfortunately, in all the photographs I found of that block, there was nothing on the corner but an empty lot.

It’s a shame those buildings were torn down, because the one at no. 174 was apparently the birth-home of Alfred E. Smith, the four-term governor of New York State and the Democratic nominee for President in 1928 (making him the first Roman Catholic to be nominated by a major political party).

It would’ve been nice if I could’ve found a photo of the famous politician’s childhood home to help confirm we found the right place, but unfortunately, nothing seems to exist other than a few hand-sketches. But after I found a 1927 blurb released by the studio touting that, “Al Smith’s birthplace will be seen in East Side, West Side,” it helped confirm that this first scene took place in front of 174 South Street.

That’s when I realized the cameraman on East Side, West Side has inadvertently provided the only photographic record of Smith’s first home.

Once I knew the location of the first part of the scene, I figured that the location of the second part —while not directly next to it— would be somewhere close. The main clue to work from was a narrow building on what looked like an acute corner. And judging by the angle and distance of the cross street behind it, it looked like the building was on a small triangular block, with only four or five buildings on any one side.

Of course, the entire area got razed in the 1950s to make way for the enormous Alfred E Smith Housing Development (which I assume was named to commemorate his birth-home at nearby 174 South Street), so we had to rely on vintage maps and photographs to figure this location out.

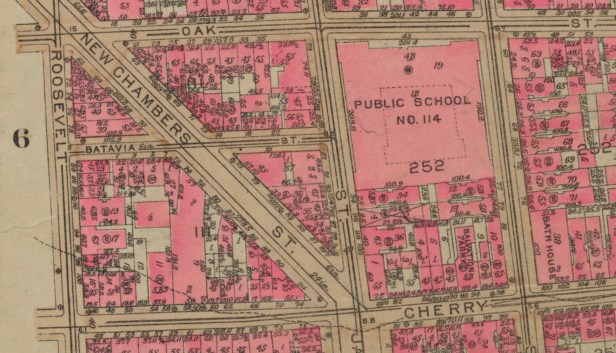

Blakeslee and I quickly zeroed in on New Chambers Street because it went on a diagonal, creating triangular blocks. As a helpful aid, the maps from the old Bromley’s land books include the heights of all the buildings, expressed in stories. So, we looked for any blocks that had buildings with the same combination of heights as the ones seen in the film, eventually focusing on an area near Cherry Street, which looked like it could be a match.

The block looked promising, and after going through the NYPL Digital Collection, I discovered a 1932 photograph of a three-way intersection of New Chambers, Cherry and James Street that was a match. Amazingly, it was taken at almost the exact same angle as the film, giving us definitive proof of the location used.

Because it was a multi-street intersection with unusual angles, I had a little trouble figuring out the exact orientation. But Blakeslee had a better handle on it, concluding that the camera was looking north from Cherry Street, while the actors ran south on New Chambers Street.

Even though director Allan Dwan filmed this initial scene on location in downtown Manhattan, most of the neighborhood street scenes were filmed on a giant indoor set, constructed at Fox’s New York studios at 850 Tenth Avenue. This ambitious recreation of a Lower East Side neighborhood took up nearly the entire studio, and not only did it include blocks of apartment buildings and storefronts, it also had full-scale elevated tracks with a moving train.

When Fox’s New York Studios opened in 1920, it was unique from other East Coast facilities, in that it had filming stages, laboratories and the corporate headquarters all under one roof. However, consolidating everything to one location may had been to its detriment, as it suffered certain limitations, most noticeably not having a backlot. This forced directors like Dwan to build outdoor sets inside, which led to some problems. For example, in 1920, while working on the crime serial, Fantomas, the crew had to quit early one day after the studio filled wth smoke from a fire scene being shot by another production.

Things slowed down quickly for the studio and by the summer of 1924, Fox had officially shut down operations in New York, and began renting out their facilities to other productions. But in 1926, Fox hired Allan Dwan after his Paramount contract ended and they briefly opened up the Tenth Avenue space to let him direct four features there, including East Side, West Side. Earlier that same year, Fox’s Movietone system premiered at their New York studios, demonstrating the process of putting sound onto film for the very first time.

Today, the building on Tenth Avenue is used as a high school, and is one of the few structures that has survived from New York City’s early movie days.

Brooklyn Bridge

Not much work was needed to figure out this location. It was clearly shot on the popular Brooklyn Bridge, and by the looks of the skyline in the background, I determined the actors were at the promenade at the eastern tower.

2024 UPDAYE: Unfortunately, when I first went to take a modern pic on the bridge, I was dismayed to see the tower and pedestrian walkway were under construction, cluttering up the shot. It was particularly disappointing, knowing that finding a time when the bridge isn’t packed with tourists is hard to come by. But finally, a few years later, I was able to take a “post-constuction” photo of the promenade one chilly February morning (as seen above).

Ticker-Tape Parade

I was fairly certain these shots of the parade were stock news footage that were simply edited into the film, but I was still interested in identifying where they took place.

Since New York’s ticker-tape parades were always staged along the south end of Broadway, I knew roughly where to start looking, and quickly recognized Trinity Church in one of the shots (seen in the 2nd image above). And even though it wasn’t officially on Broadway, I was almost certain the building in the 1st image was the Whitehall Building on the nearby Battery Place. I recognized the building’s windows from the Harold Lloyd movie, Speedy, where his horse-drawn trolly crashes into a pole not far from it.

The Woolworth Building was identified by Blakeslee, which made geographical sense since the ticker-tape parade for Lindbergh ended at City Hall Plaza, right across the street from the building.

The fact Allan Dwan was integrating 1927 news footage into a film that was being released that same year shows how fast and nimble of a director he was. By bringing current events into the story —like the Lindbergh footage in this scene and an image of the newly-constructed New York Telephone Building in an earlier scene— he undoubtedly made the film feel more fresh and contemporary to audiences. Another example of this is in the last scene of the film which features a skyscraper that was a big news story only a few months before East Side, West Side was released to theaters. (See “On a Balcony” below.)

Working on a Subway

Like several locations from this film, Blakeslee and I tag-teamed this one, with him ultimately finding the exact spot the action took place.

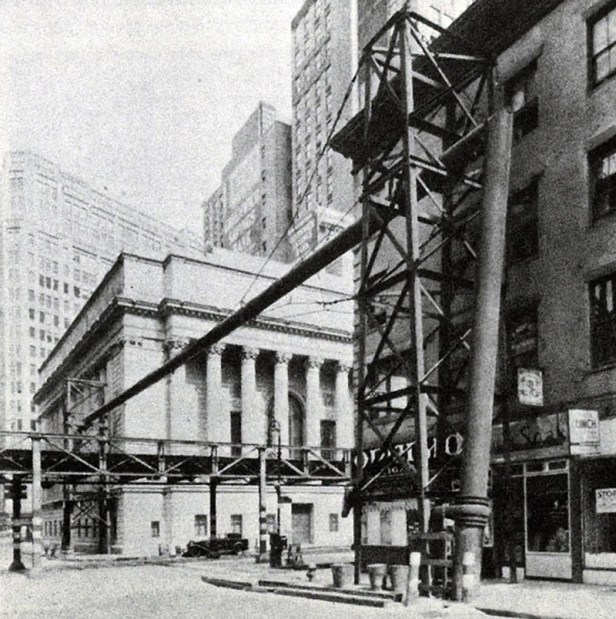

When we first began working on this location, the one big clue we focused on was what looked like El train tracks that appeared in the background of the scene. However, several months later, Blakeslee and I came to a realization that what we thought were elevated tracks in the distance, might actually not be tracks at all. This came about when we noticed that there weren’t any metal support columns on the street corners, which would’ve been necessary if it was an El train.

Then came the question: if it wasn’t elevated train tracks, what was it? I had no idea.

After sifting through ab bunch of old photos from that era, Blakelsee began thinking that what we were looking at might actually be construction gas lines. He came to this conclusion when he found a 1914 image of a subway line being built with gas lines being re-routed along wrought-iron bypass mains suspended above the street. This was done to avoid potential gas explosions when excavating the street, and from a distance, the larger mains looked like El tracks.

Thinking he was onto something, I did a little research into what might have been under construction in 1927 and discovered that the Eighth Avenue IND subway was being built at that time. Armed with that information, we were able to find a couple pictures of the IND being worked on, which showed more of those gas lines stretched above the street, giving a similar appearance to what was in this scene.

That’s when Blakeslee took the reins and looked through loads of vintage photos of Eighth Avenue, looking for something that matched the scene. The first thing he found was a 1932 image looking north on Eighth from around 22nd Street, featuring a prominent office building at 322 8th Avenue (est. 1925), which seemed to match the faint distant building in the film.

Now certain that the camera was pointing north on Eighth Avenue somewhere south of 22nd, he carefully studied several other photographs until he found one from 1927 of the northwest corner of W 16th Street. Even though the scene only had a limited view of the western blocks, he was still able to find several matching elements with the 1927 photograph. This seemed to indicate that the elevator was most likely somewhere between 14th and 16th Streets

A little later, Blakeslee found a ca 1940 photo in the NYC Municipal Archives that showed a matching building on 17th Street and a 1928 photo in the NYPL Digital Collection that showed a matching sign and building near 18th. These images further proved we were on 8th Avenue but didn’t help in figuring out where exactly the elevator was located.

After doing some searching of my own, I was able to find a ca 1930 photo of the block between 15th and 16th that showed some details that matched what appeared in the scene on the far left side of the frame.

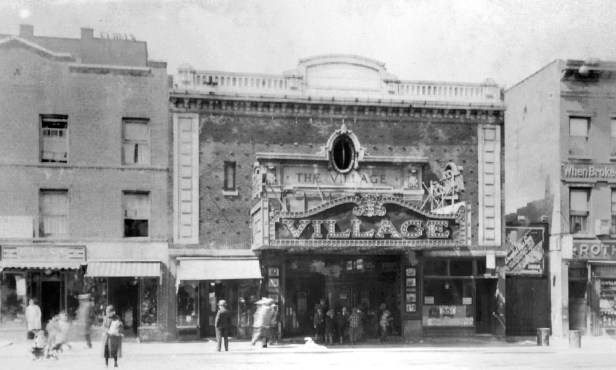

When I shared the photograph with Blakelsee, he determined that the vertical white strip on the left was for the Village Theatre at 115 Eighth Avenue. After consulting a period map, he could see that the short-lived movie house was near the middle of the block. That meant the elevator was just to the south of it, placing it near the northwest corner of 15th Street.

While most of the buildings that appeared in this scene are now gone (the entire block between 15th and 16th got replaced in 1932 with the giant “811 Eighth,” which is the fourth-largest office building in NYC and currently owned by Google), some key structures are still around. The two most noticeable are the residential building on the northeast corner of 17th Street (est. 1920), and that distant office building at 322 8th Avenue, both of which helped confirm this elusive filming location.

On a Balcony

Although I didn’t immediately recognize it, the building featured at the beginning of this last sequence was pretty unique looking, and I figured I’d be able to identify it if I did a little digging. With the presence of scaffolding on the tower, I guessed that the building would have a construction date on or around 1927, so I decided to search through a bunch of online databases that listed NYC skyscrapers by year.

Eventually, I came across the Sherry-Netherland Hotel on Fifth Avenue (est. 1927), which looked like a match, and to my utmost surprise, is still standing today. I was surprised because a lot of these early Beaux-Arts skyscrapers have met with the wrecking ball over the years, such as the Sherry-Netherland’s southern neighbor, the Savoy-Plaza Hotel (also est. 1927), which was demolished in late-1965 to make way for the General Motors Building.

Actually, the Sherry-Netherland Hotel almost didn’t make it past 1927, when a fire broke out on some wood plank scaffolding surrounding the uppermost floors during the last stages of construction. On April 12th, around 8pm, the top of the skyscraper became engulfed in an enormous blaze, which was so brilliant, that it was said to be visible all the way from Long Island.

The main problem was the fire department didn’t have enough water pressure to reach the higher floors, so they ended up having to watch idly as the tower continued to burn. And they weren’t the only ones.

As flaming planks tumbled to the street and the blaze raged 38 stories above Fifth Ave, hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers watched from all around the city, awed by the “free show.” In fact, the more affluent spectators immediately rented out rooms at the Plaza Hotel (which was diagonally across from the burning tower) to have “fire room parties.”

The blaze eventually burned itself out later that night, and amazingly, only the exterior was affected. Apparently, the damage was minimal enough that the hotel still managed to have its grand opening later that year, only one month behind schedule.

What’s interesting is that this scene from East Side, West Side was shot in the summer of ’27, which was in-between the fire and the official opening in November. I’d be curious to know if Dwan specifically used this location because it was recently in the headlines.

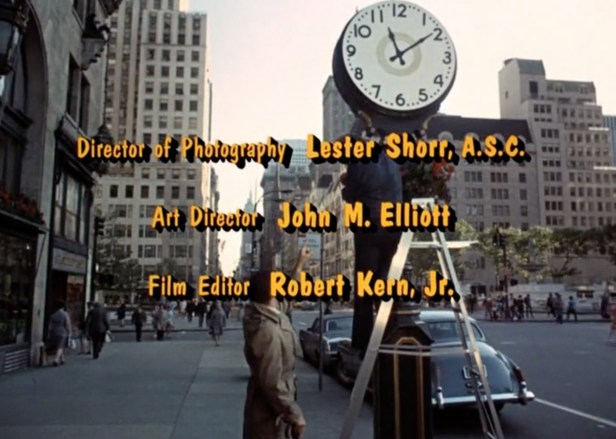

Over 40 years later, the Sherry-Netherland Hotel would be immortalized in the closing credits of The Odd Couple TV series, where Felix corrects the workman adjusting its street clock outside the main entrance.

After identifying the Sherry-Netherland Hotel, I faced the problem of figuring out what terrace the two characters were on at the very end of the film. Based on its view of the Sherry-Netherland, the terrace obviously couldn’t be too far away, but I had trouble figuring out the specifics.

To help speed up the process, I brought in Blakeslee to lend a hand. And it didn’t take him too long to conclude the terrace was part of the Warwick Hotel on 54th and 6th Avenue.

He found it by first using the vantage point of the three skyscrapers on Fifth Avenue to get a general idea of where they were. Since the Crown Building (second building from the left in the picture below) was on the west side of 5th Ave, the terrace was probably near 6th Ave. And thanks to some promotional photos that showed a little bit more of the skyline, he was able to use the Ritz Tower (which is on 57th Street) as a landmark to help him narrow down the possibilities even more.

Besides the Ritz, another thing that was in the promotional photos but not in the film was a set of intricate columns that were built into the terrace wall. The columns formed a unique pattern that made it stand out from similar walls. Since Blakeslee knew that the scene was most likely filmed in a building along Sixth Avenue and south of 57th Street, he looked in that area until landing at the Warwick Hotel on 54th Street, which had a matching terrace wall.

Built only one year before this scene was filmed, the 36-floor Warwick New York was the brainchild of media tycoon, William Randolph Hearst, who wanted a luxury residential hotel to accommodate his Hollywood friends, including his long-time mistress, actress Marion Davies. Hearst even had a penthouse suite specially-designed for her, which later became the semi-permanent residence of Cary Grant in the 1950s.

Other guests who have stayed at the Warwick New York, according to the hotel’s website, include James Dean, Jane Russell, Elizabeth Taylor, and Elvis Presley. And in the summer of 1966, the hotel was swarmed with teenagers when the Beatles stayed there during their third and final concert tour in the US.

Other guests who have stayed at the Warwick New York, according to the hotel’s website, include James Dean, Jane Russell, Elizabeth Taylor, and Elvis Presley. And in the summer of 1966, the hotel was swarmed with teenagers when the Beatles stayed there during their third and final concert tour in the US.

While the Warwick is still around today, it’s now surrounded by the enormous MGM Building at 1350 Sixth Avenue, which blocks any views of the Sherry-Netherland Hotel on Fifth.

Needless to say the third “before/after” image above wasn’t actually taken from the hotel terrace, but was a screenshot of Google’s 3D View, taken from approximately the same vantage point. I included it to show how many more skyscrapers fill the landscape today.

Like the Becka character in this scene said, “Building, John — always building. We tear down and build up. When is it going to stop?”

While not a masterpiece, East Side, West Side is an exceptionally strong film that showcases several NYC locations, obviously showing director Allan Dwan’s fondness for the always-evolving metropolis. Dwan was never a great fan of Hollywood, and seeing that most of the East Coast studios would soon be gone, he took the opportunity in 1926 to make a last-ditch, four-picture deal with Fox, so long as he could use their New York facilities.

Interestingly, while he shot the interiors at the Tenth Avenue studio, the location-shooting for three out of his four films were done outside of New York City. Only this film took place and was entirely shot there.

And he took full advantage of the rich and eclectic offerings of the Big Apple. Not only did Dwan surround his leads with the real-life textures of actual New York locations, he also took the opportunity to fill the scenes with colorful locals, some of whom were recruited right off the city streets. So even in the scenes that were shot on a set, the unmistakable flavor of 1920s New York is ever-present.

When asked about working with Dwan on this film, actor George O’Brien said they got along fine, even though the Canadian-born auteur had a reputation of being “prickly” and “sarcastic.” But how could you say something bad about one of key players in early cinema, who not only directed such stars as Gloria Swanson, Douglas Fairbanks Sr, Shirley Temple and John Wayne, but was also a technical whiz, reportedly having a hand in inventing the dolly and crane shots.

Dwan worked at many studios over his long career, but always retained enough clout to be able to make the kinds of movies he liked. And it’s clear with East Side, West Side, he made the kind of movie he liked, giving a befitting tribute to New York City.

Wow, absolutely brilliant reporting and detective work. Thank you so much Mark

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a fabulous article! Thanks so much! We adore this film, which we scored for Le Giornate del Cinema Muto in 2001 and have just finished recording a revised score which accompanies the restored MoMA print next month on the Criterion Channel. Best wishes, Donald Sosin and Joanna Seaton oldmoviemusic.com

LikeLike

That’s fantastic! ESWS deserves a great score. Always thought of ESWS as a worthy companion piece for The Crowd. Glad you enjoyed the article and happy that there are still folks out there who appreciate the silent era in movie history.

LikeLike