An old fashioned nail-biter that has become somewhat overlooked over the years, Marathon Man was an essential social-thriller of its time, and has one of the most iconic lines in cinema history. Often overshadowed by other NYC neo-noirs such as The French Connection or Taxi Driver, this Dustin Hoffman/Lawrence Olivier film is both thrilling and thought-provoking, filled with deeply nuanced performances by its leads.

The movie is about a New York grad student who witnesses the murder of his brother and then finds himself pursued by shadowy government agents, along with a Nazi war criminal who is trying to retrieve smuggled diamonds.

Filmed in Paris and New York, Marathon Man features a bunch of real-life locations. As might be expected, I focused most of my attention on what was shot in NYC, but I’ve also included a few of the French locations, as well as some Los Angeles locations that doubled for the Big Apple.

Old Man Confrontation

Being one of my favorite action thrillers from the 1970s, Marathon Man was one of the first titles I delved into when I began this “NYC in Film” project back in 2016. What’s interesting is that back then —just seven or eight years ago— information on movie productions was much more incomplete than it is today. There were a few websites out there that listed some of Marathon Man’s locations, but they had a lot of holes in them, even when some of the places seemed to be fairly findable.

Case in point, none of the locations from this or the ensuing car chase sequence were documented on any websites back in 2016 (at least not anywhere I could find). It was pretty surprising, considering almost all of the major spots featured in these sequences had informative signs visible in them. So, in most cases, it was just a matter of spotting a street sign or looking up the address of an old store.

The other thing I was interested in investigating from this scene was the old man playing Szell’s brother. He was credited as Ben Dova, which almost sounded like some “Crazy Credits” fake name.

The actor’s real name was Joseph Spah, a German-born contortionist and acrobat who, after immigrating to Queens in 1922, adopted Dova as his American stage name. One of Spah’s signature acts was performing acrobats atop tall skyscrapers, including NYC’s 56-story Chanin Building, which was featured in a 1933 newsreel (pictured above).

Spah performed all over North America and Europe, and it was on one of these tours that he ended up on the Hindenburg during its final fatal trip in 1937. Incredibly, he managed to escape the disastrous crash by leaping from the airship (undoubtedly using his acrobatic skills) just as it was going down in flames.

Ironically, his character will die in a fiery explosion at the end of the following car chase sequence.

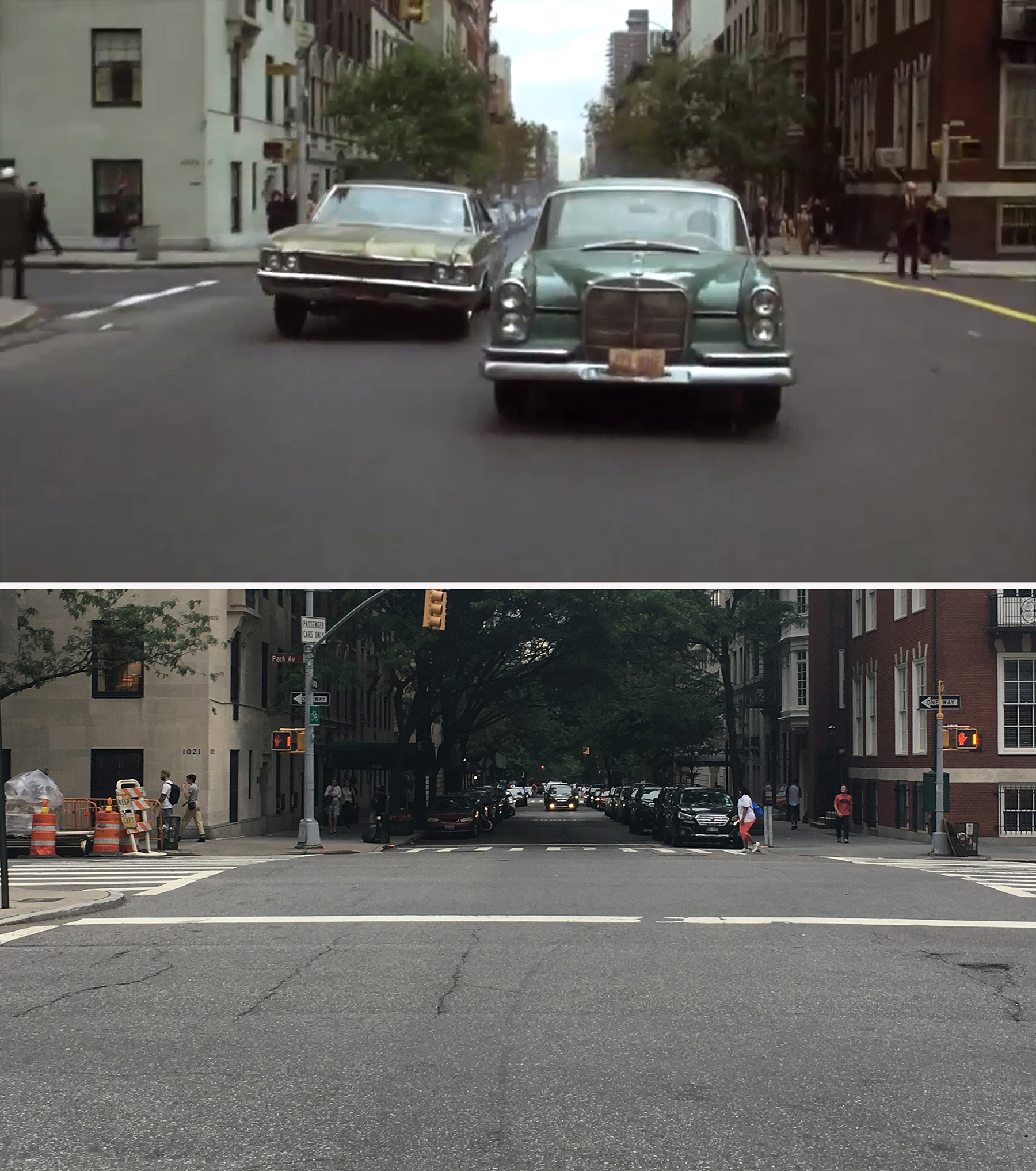

Car Chase

Like I mentioned above, pretty much none of these locations were identified on any websites when I began researching this movie in 2016.

And I must say, I remember at the time, I was very proud of myself for finding all the locations from this chase sequence, especially since there are quite a few geographical inconsistencies throughout it. (They even used the Park and 85th Street intersection twice during the chase.) It’s kind of fascinating how when I was new to this whole location-searching process, it was quite exhilarating when I was able to solve any mystery, no matter how obvious it may seem today.

Back in 2016, there was one location from this sequence that was already listed on IMDb and a couple other movie websites, and that was for the climactic explosion.

This ending to the car chase was shot on E 91st Street, wedged between a couple well-known New York institutions — the Cooper Hewitt Museum on the south side and Convent of the Sacred Heart on the north side. This is an area that has been used in a bunch of other films, such as The Anderson Tapes (1971), Arthur (1981), Jumpin’ Jack Flash (1986) and Working Girl (1988).

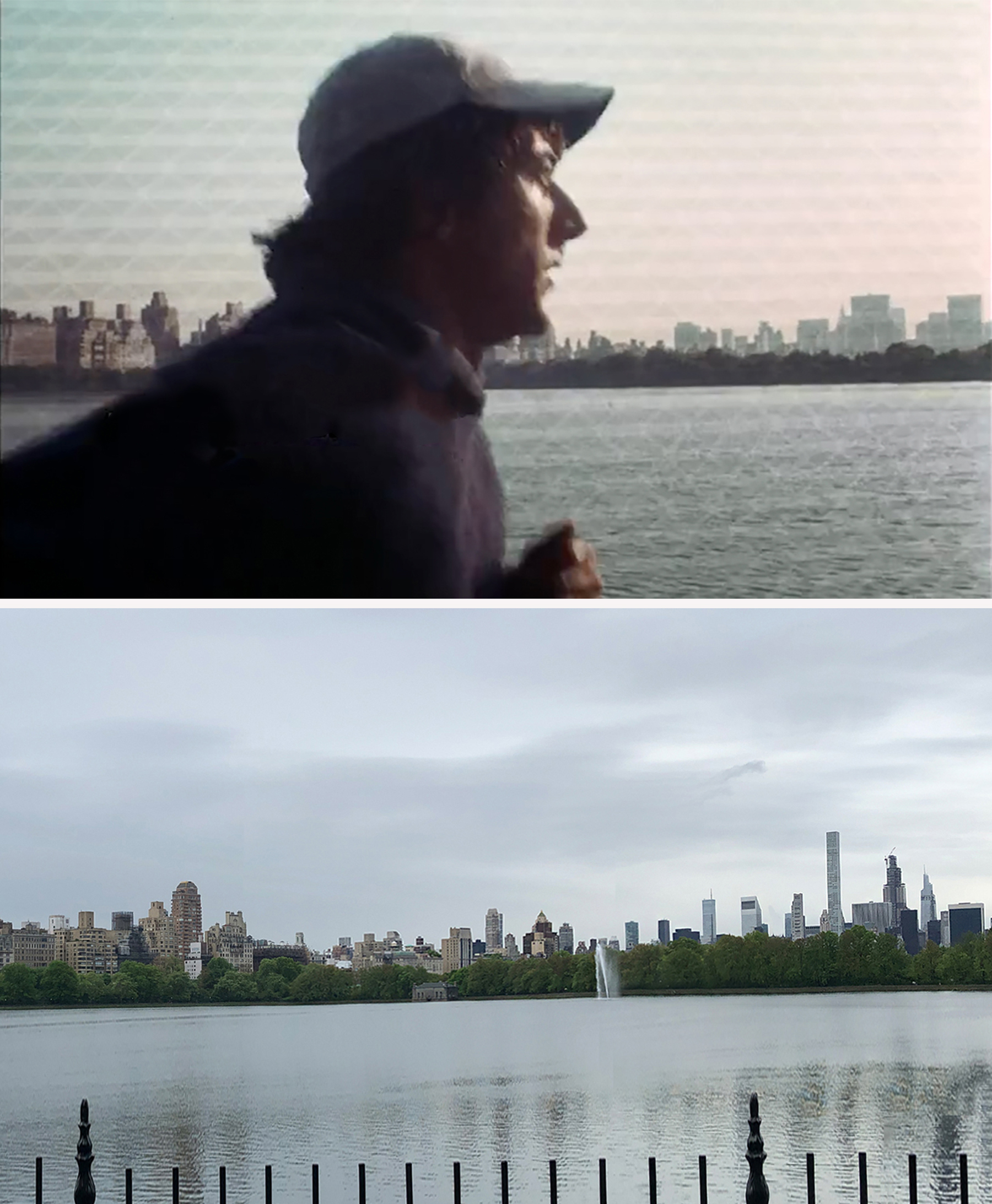

Babe Running

Several websites have identified these running scenes as taking place at the famous Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir in Central Park. However, aside from the North Gate House, no one specified the exact spots used on the track, so I felt obliged to find as many as possible.

Even though most of my research on this film was done in 2016-17, this task of finding all the specific reservoir spots was done just a few weeks ago. It wasn’t a particularly difficult job, but it was a little time-consuming lining up the curves of the reservoir with the views of the skyline. And it wasn’t just a matter of matching up the buildings in the distance, I also had to make sure that the angles were just right. This was to make sure I found the correct spot on the running track which has parts that are practically indistinguishable from other parts.

Of course, like in the previous car chase sequence, the rival running sequence has a few geographical inconsistencies, jumping from one part of the track to the other. This added to the difficulty of identifying all the locations, but fortunately they were all on the northern half of the reservoir, never going further south than E 89th Street.

One thing that helped me nail a few of these spots was the placement of the lampposts which appear to be in the same place they were in in the 1970s.

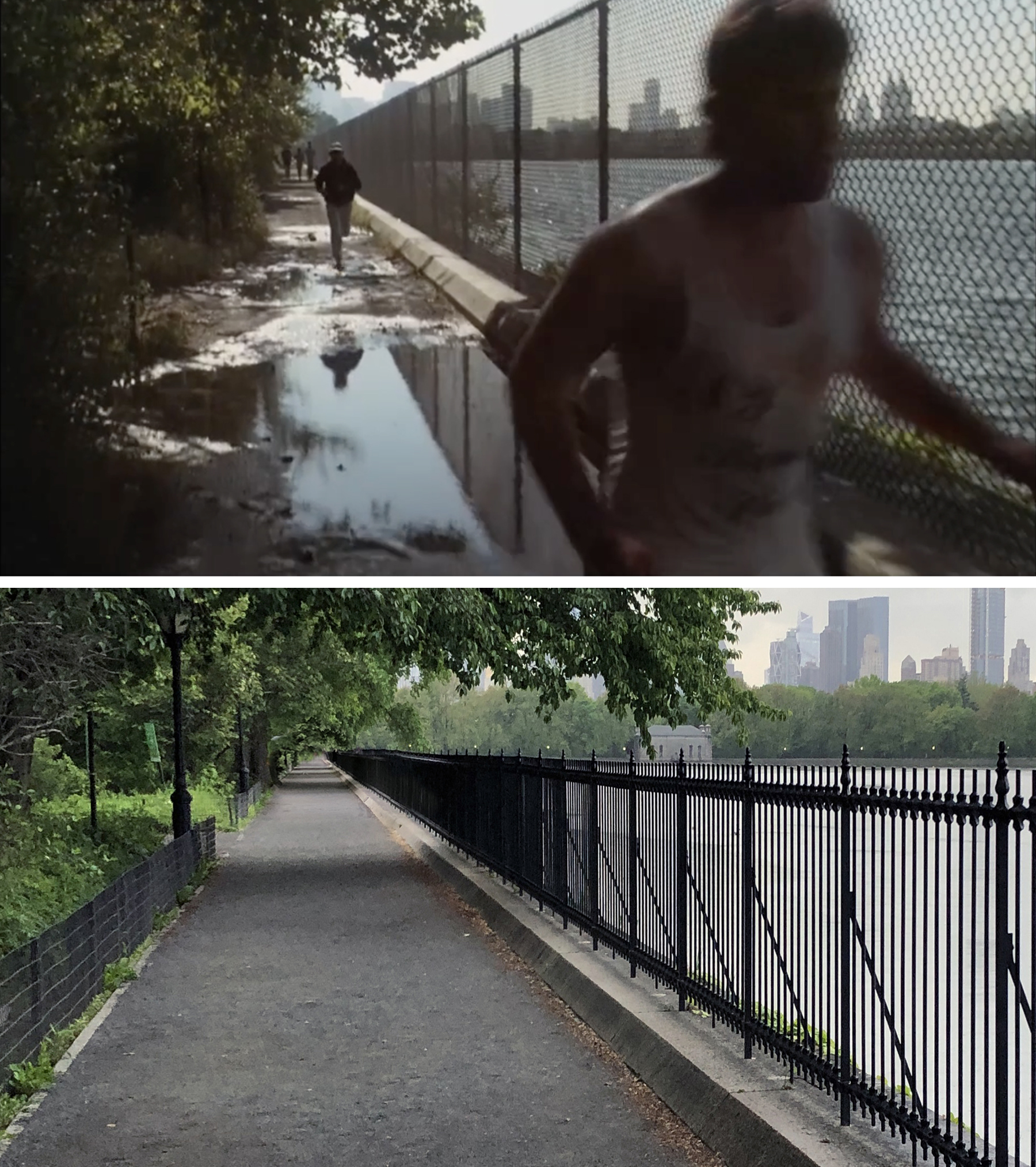

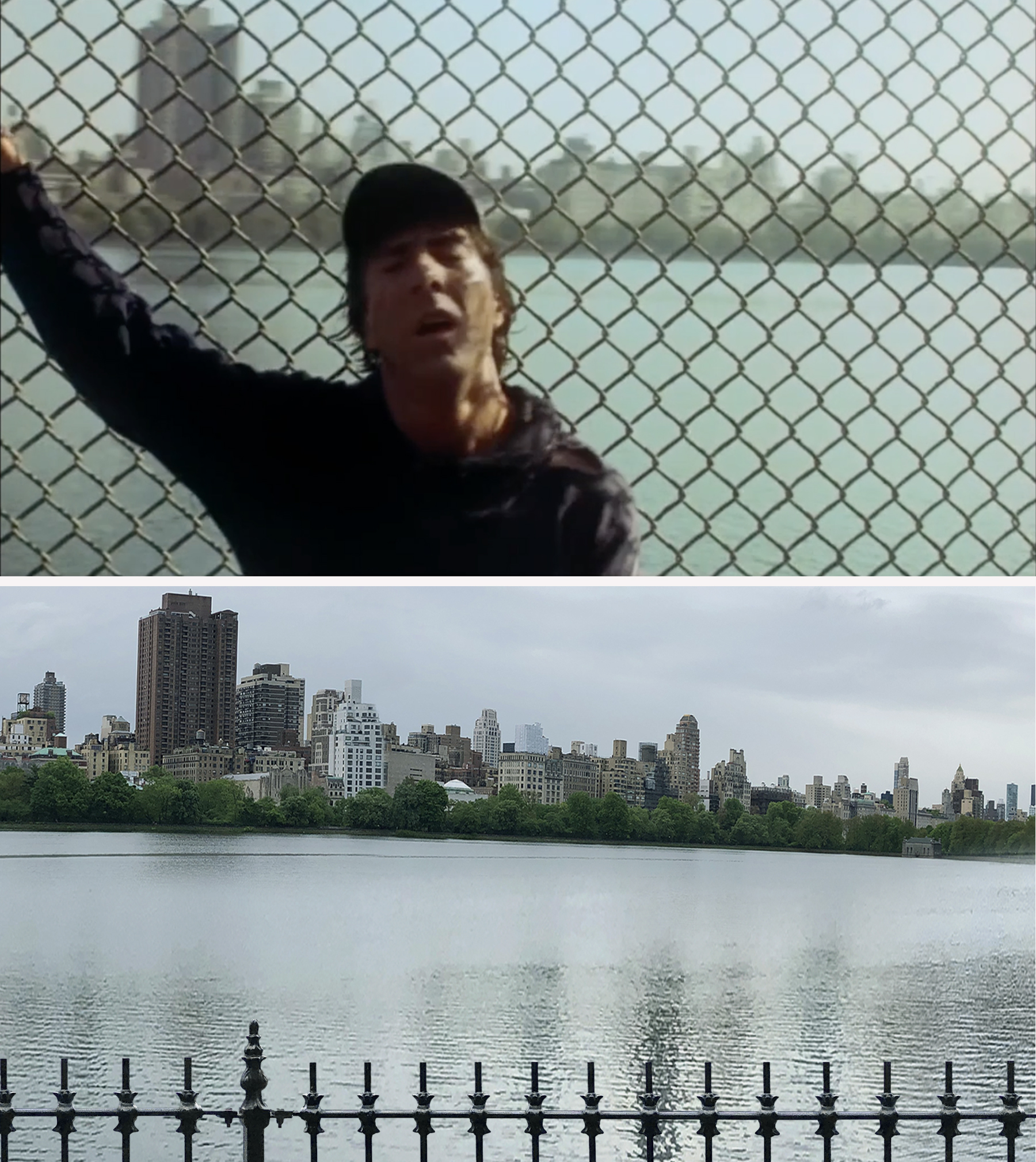

However, one thing that has changed since the 70s is the removal of the ugly chainlink fence that surrounded the entire body of water.

When this northern reservoir was first built in the 1860s, it was surrounded by a wrought iron fence similar to the one that’s there today. But in 1926 it was replaced with the tall chainlink fence seen this film, topped with barbed wire. In an acerbic letter to The Times, novelist Edna Ferber described the new fence as “hideous,” complaining, “one cannot look through it without getting seasick and cross-eyed.”

The reason given by the Department of Water Supply for adding this higher barrier was to help reduce suicides which were apparently a regular occurrence at the reservoir. But Ferber wasn’t buying it and retorted with a tongue-in-cheek threat, ”I will scramble over the thing myself some dark night in spite of its height and you will see me floating on the first page next morning, face up—just to spite them.”

The new iron fence that was finally installed in the early 2000s is a near replica of the 19th century original, and measuring at only four-and-a-half-feet tall, it offers visitors panoramic views that were previously obstructed by the seven foot fence. It’s a lovely feature that helps make the reservoir all the more charming.

Another charming (and yet utilitarian) feature is the set of gatehouses that are used to pump the water in and out of the reservoir.

The reservoir is divided along its center into two separate basins, and before it was decommissioned in the 1990s, was fed via a brick tunnel and iron pipes from the Croton Aqueduct in Westchester. The gatehouse on the north end brought the water in, and the the gatehouse at the south end distributed the water to other parts of Manhattan. But you might notice that there are actually two granite structures on the north end (shown in the third “before/after” image above).

The smaller one confused me at first (as to its function), but I eventually learned that it was simply an auxiliary gatehouse. Built in the 1880s, it was considered more sophisticated in design than the original gatehouses, but no less charming.

There’s really nothing more relaxing than strolling around the reservoir, especially at night where the number of joggers is significantly reduced. In the daytime, particularly during the afterwork hours, the crushed gravel track is packed with joggers, walkers and dog owners, all jockeying for position. In fact, there is so much competition for the path that one-way signs have been posted to try to maintain some sort of order (although they are often ignored by oblivious tourists or “I-don’t-give-a-shit” New Yorkers).

While the track can get a little hectic during the warmer seasons, things get more serene in the winter. But that wasn’t the case one week in January, 1893 when a peculiar event drew a crowd of over a thousand to the shores of the iced-over reservoir. The thing of great interest was a lone dog that had been spotted circling the icy waters for several days. No one knew why it was there and no one knew how to rescue it — the ice was deemed too thin to support a human. Some wanted to shoot the dog to put it out of its misery, but concerned animal activists put a stop to that plan.

Described in the New York Times as “Central Park’s Dog Demon,” the distant pooch continued to zigzag around the frozen lake both day and night. By the time it was finally rescued, the beleaguered dog had been out on the ice for five days. Thomas Ward, one of the rescuers and an employee at a livery stable on E. 102nd Street, decided to keep the canine as a pet, so this odd little story had a happy ending.

Babe’s Apartment

Once again, when I began investigating this film in 2016, no one had identified Babe’s apartment, even though it was prominently featured in several scenes. And there’s even a nice clue in one of the shots — the number 435.

These days, if a scene has an address number without a street name, I will normally go to the 1940s tax archives and use its search engine to find all entries with that number. It’s a great way to see thumbnails of all the buildings, which can easily be scanned for matching architecture. While not a perfect system, when faced with this scenario, it’ll usually help me find a missing location 4 out of 5 times.

But back in 2016, the 1940s tax archives were not available online. So in this instance, I had to use Google Street View to go through the 435s on different streets, trying to limit my search to neighborhoods that looked like the one used in these scenes. I thought it looked like the Upper West Side, while my research partner, Blakeslee, thought it looked like Chelsea or Hell’s Kitchen. So, we divided and conquered, with Blakeslee being the one to eventually hit pay dirt.

Afterwards, he shared this discovery with at least one other movie website to help get the info into the web-o-sphere (as this was before I decided to launch this “NYC in Film” website).

When it came to the interiors of Babe’s apartment, that wasn’t shot on location. It just a set built on the Paramount lot in Hollywood.

As far as I can tell, the real building at 435 W 47th Street is not subdivided into individual apartments like in the movie. Although, by the looks of its exterior, I think the building either has been vacant for quite a while or at the very least, mostly unused.

Doc in France

I can’t remember how many of these French locations were identified when I first investigated this movie back in 2016, but as I was preparing this article, I could see that pretty much all of these European places were now listed on at least a couple websites. And thankfully so, because I’m not sure how well I would’ve fared in finding them on my own.

That being said, I did have to find the very first Parisian location, which was inexplicably not mentioned on either IMDb or Movie-Locations.com. It was kind of surprising, seeing that the scene took place near the Arc de Triomphe, probably one of the most famous landmarks in the city (next to the Eiffel Tower). And of course, it was this iconic arch that helped me find this unidentified location.

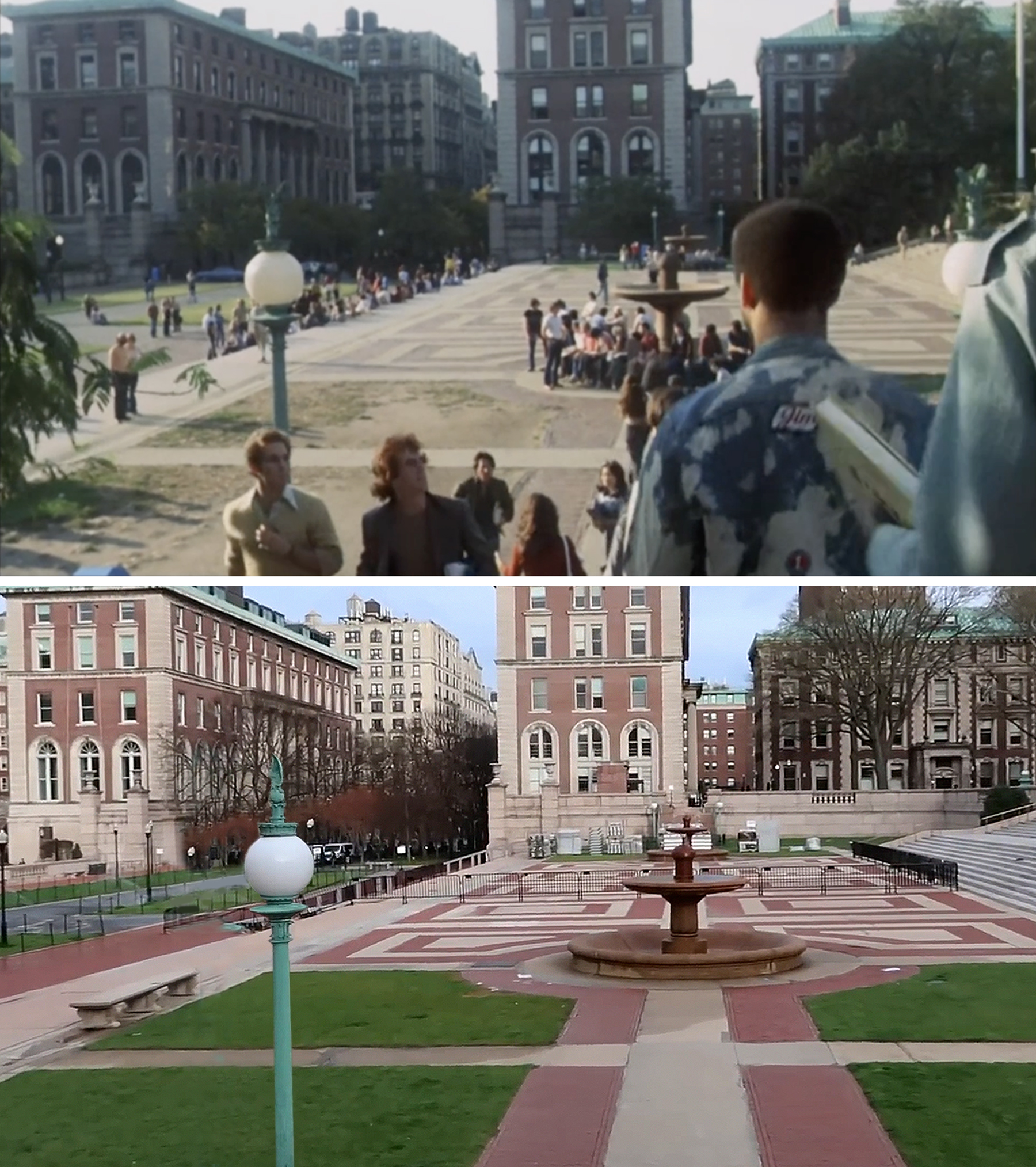

Columbia University

If there’s a university scene in a New York City movie, you can almost bet that it will be taking place at Columbia. This is probably because of all the colleges in the city, Columbia is the most photogenic, with nice old buildings on a classic campus. You can see this Ivy League school in a ton of movies like Ghostbusters, Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man series, Malcolm X, and the gory Italian slasher, The New York Ripper.

While shots of the campus were real, the college interiors were shot on the West Coast. The library where Babe gets to meet Elsa Opel is the Doheny Library at the University of Southern California. Interestingly, a couple years back, USC masqueraded as Berkeley’s campus in Hoffman’s debut feature, The Graduate.

The last bit of Babe running across the street outside the university was back in New York. And it being a high-angle shot looking down on Amsterdam Avenue, I thought matching it would be impossible without a drone or something.

However, there is actually a second-story plaza that stretches over the Avenue between 116th and 118th Streets, making it easy as pie to get a matching modern pic.

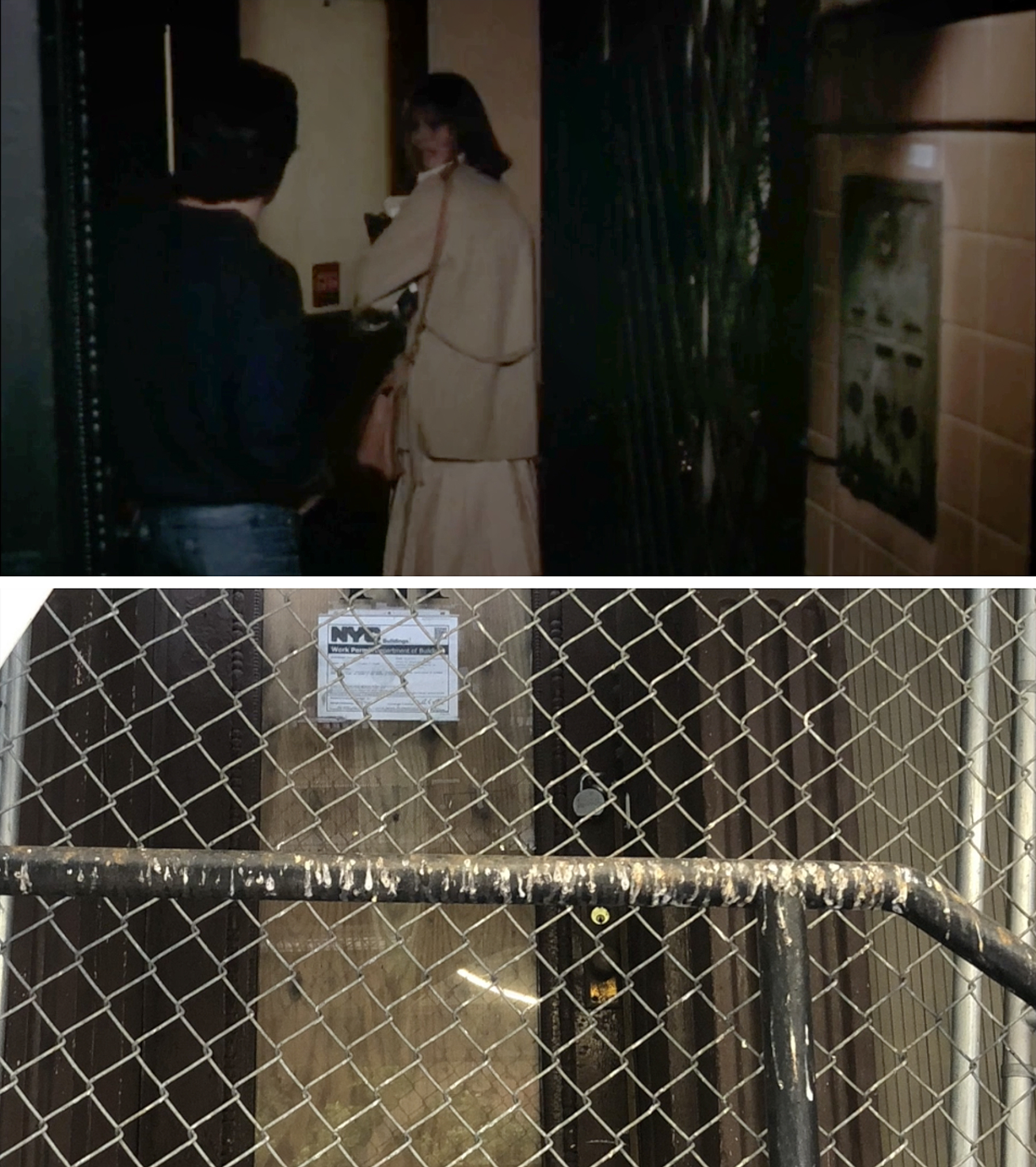

Elsa’s Apartment

This was another location that was unknown back in 2016 when I first tackled this movie, and I was eager to jump at it.

Naturally, with a street sign clearly showing they were on West 94th Street, I figured I’d get this location solved within minutes. But after checking out every W 94th corner in Google Street View, I couldn’t find a match.

That’s when I started to suspect that maybe the street sign was fake. I assumed they put a fake street sign up to make the location appear closer to Columbia University than it really was.

So from there, I focused on the other signs that appeared in the scene, turning to the large “Health Education Center” banner hanging from the second story along with the awning below with the name, “Mayer Hill Hospital” on it. But I soon assessed the awning lettering was fake because I found zero info for a Mayer Hill in NYC.

If you look closely, you can see the word “MAYER” is slightly different looking from the word “HILL,” so I guessed that that was the only part replaced by production. And if that was the case, then we were probably in one of two Manhattan neighborhoods — Lenox or Murray Hill.

When I searched in Google Books for “Health Education Center” alone, I got too many hits, but when I added “Lenox Hill,” I immediately got several helpful links, many of which gave an address of 1080 Lexington Avenue, placing the center on the corner of E 76th.

Feeling hopeful, I checked out the address in Google Street View and sure enough, it was a perfect match. It even had that unique stone staircase leading to the second floor. Only problem now is, the building has been shrouded in construction scaffolding since 2015.

Hoping the property owners put the scaffolding up for repairs and not demolition, whenever I was walking around Lenox Hill, I’d swing by 76th and Lex to see if it had been removed. But year after year, nothing changed. It also appeared the building was completely vacant, which made me think it was slated for demolition, but again, year after year, nothing changed.

That brings us to 2024 and while the building still seems vacant, curiously, the scaffolding has been updated with nicer poles and more attractive boards. That makes me think that maybe the owners are not planning on tearing it down, but it’s hard to know for sure. We’ll just have to wait, hopefully not year after year.

Central Park

Getting Mugged

Most of these scenes in Central Park were easy to find since they were shot either at places already identified —like the North Gate House on the Reservoir— or they had obvious landmarks in the frame like Bow Bridge at Cherry Hill or the fountain at Bethesda Terrace.

The only part that was unclear was the actual mugging scene. When the two characters leave their bench in the previous scene, they walk west, initially making me think that is where the mugging took place. But it turned out, the geography was a little twisted around, and the mugging actually took place to the east inside the Ramble, located on the other side of Bow Bridge.

I’m pretty sure I got the correct spot, but with very little details in a darkly photographed scene, it’s hard to know for sure. The clues I went off of was the curve of the path, as well as the presence of a parallel path just below the main one, which in turn, seemed to be next to the Lake. In the end, I could only find one place in the Ramble that matched all of those elements.

As a side note, in my recent write-up on the 1981 thriller Ms .45, I talked about some of the oldest manhole covers found in Manhattan. In my descriptions, I concluded that the oldest was on 8th Avenue across from the Port Authority Bus Terminal, but it turns out, there is an older one not too far from the North Gate House.

Just to the north of the reservoir, right next to the Ladies Room at the Central Park Tennis Center is an 1861 manhole cover that predates any other known covers on the island. Avid manhole cover researcher, Don Burmeister surmised that the hole is probably connected to a drainage pipe that would carry overflow from the reservoirs to northern bodies of water like Central Parks’s Pool near W 98th Street. It’s one of those fascinating pieces of New York history, hidden in plain sight.

As to that other manhole cover on Eighth Avenue, months after my discovery, the old relic was removed by the NYC Department of Environmental Protection and replaced with a generic cover. Apparently it’s now being stored in the DEP Archives for “safekeeping.” Not sure if the fear was that the cover was in danger of be stolen, but if that’s the case, then the one in Central Park will likely be removed as well in the near future.

Szell Travels to America

These were locations I didn’t bother to investigate when I first examined Marathon Man in 2016. But both the “South American” jungle and airport have since been documented.

I was surprised to discover that what was supposed to be Uruguay was really a botanical garden in Los Angeles Country. Not that I thought the crew really went down to South America, but I thought it might’ve been someplace a little more exotic.

The LA County Arboretum has been used in a bunch of other productions, including The African Queen (1951), Terminator 2 (1991), Jurassic Park (1993), and the TV series, Fantasy Island. In fact, the bell tower on top of the cottage was featured in the show’s opening credits where Tattoo yells the famous line, “De plane! De plane!”

The aerial shot of Lower Manhattan is interesting, as it shows the southern tip just before Battery Park City was developed on the west side. At the time they filmed it in 1975, the landfill process was just about done, but it would be another five years before any residential construction would begin.

Today, the 92-acre neighborhood is filled with high-rise condominiums, business and entertainment centers, as well as the esteemed Stuyvesant High School.

The airport scene was filmed at the TWA Flight Center at JFK, made obvious by its strikingly Neo-futurist and Googie architecture. The terminal operated from 1962 to 2001. After it closed, the head house was renovated with intentions of preserving the facility.

After being partially used by JetBlue airlines for a few years, the former TWA Flight Center was converted into the TWA Hotel. The new hotel has maintained the 1960s vibe, preserving many of the original architectural designs, while also installing replicas of some of the original fixtures.

One of the more impressive hold-outs from the original Flight Center is the large departure board with its antiquated split-flap display.

The lounge area in the lobby has also fully embraced that kitschy sixties vibe, even if the drinks and snacks most definitely have 21st century prices. The cost of a room is also a little on the steep side, compared to most airport hotels. But what’s interesting is the rooms can be booked for daytime stays on an hourly rate. Currently, a two-hour stay in a Deluxe Double Queen room goes for $155.

Restaurant

I only figured out this restaurant location a few weeks ago, mainly because I hadn’t bothered to investigate it before.

While the menus in the scene had the name of a popular NYC French restaurant, L’Etoile, I had a feeling it was really shot in LA. This was mainly because I was pretty sure Roy Scheider, who played Dustin Hoffman’s older brother, never went to New York; he just filmed in Paris and Los Angeles.

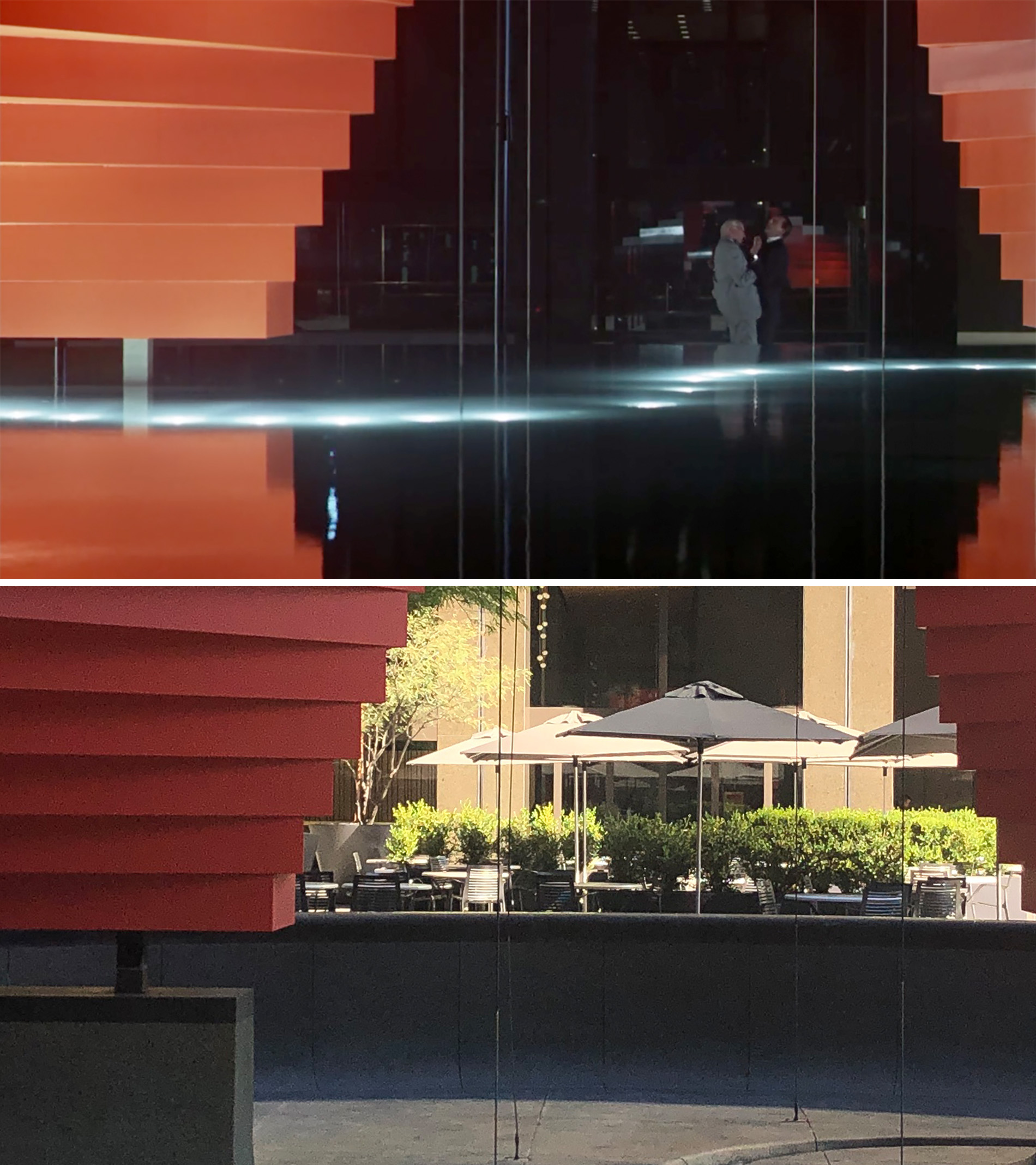

I eventually found the location by doing a Google Reverse Image search, using a screenshot from the movie. I immediately got a bunch of matches to a scene from Scarface (1983) which looked like the same restaurant from Marathon Man. From there, I looked up the locations of Scarface and saw they filmed at the former Perino’s restaurant on Wilshire Boulevard in LA.

Founded by Alexander Perino, his eponymous restaurant first opened in 1932, catering to Hollywood’s rich and famous. In 1950, Perino’s moved to a larger location two blocks away at 4101 Wilshire. The new, New Orleans-inspired restaurant became even more successful than its predecessor, serving the who’s who of celebrities, and remaining an exclusive hotspot until its closing in 1986.

Almost since its inception, Perino’s was designated a Los Angeles landmark, like Chasen’s or the Brown Derby, and eventually became a popular filming location for both film and television. This continued even after the restaurant closed, lasting until the building was sold and demolished in 2005.

In its place is a large apartment building whose lobby lovingly retains mementos from the restaurant. Fellow location-hunter, Lindsay Blake, went to the apartment building a few years ago and was amazed by how much they kept from the historic eatery.

Off the apartment building’s lobby, where Perino’s main entrance used to be, is a lounge area named the “Remembrance Room,” which actually has the original bar and wall paneling from the old restaurant.

It’s pretty impressive considering how rare it is that a new building in Los Angeles would take the time and spend the money to preserve a little bit of Hollywood history. And it’s incredible the property manager not only allowed Lindsay to look around and take those great pics, but by her account, he was actually enthusiastic that someone was taking an interest.

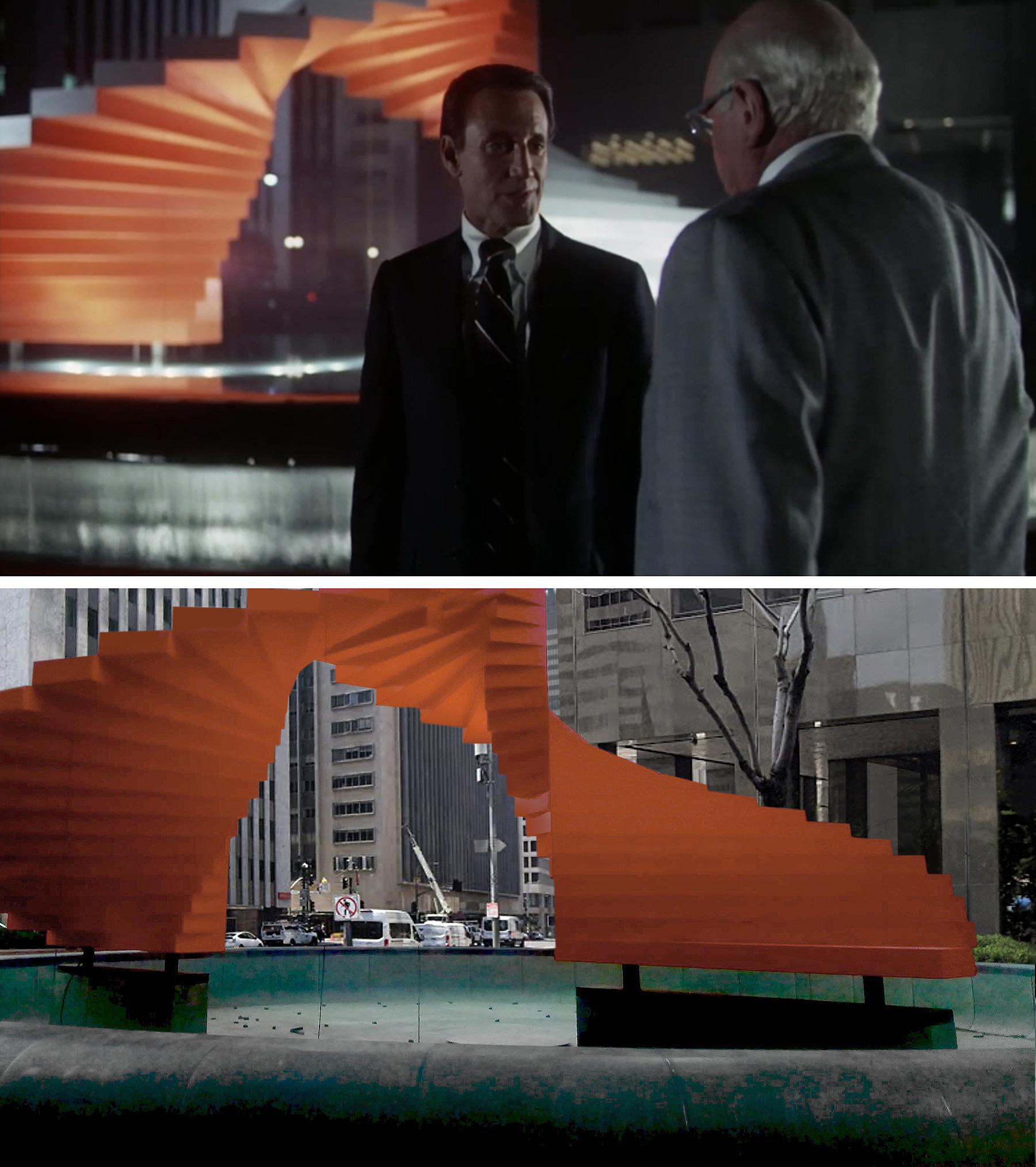

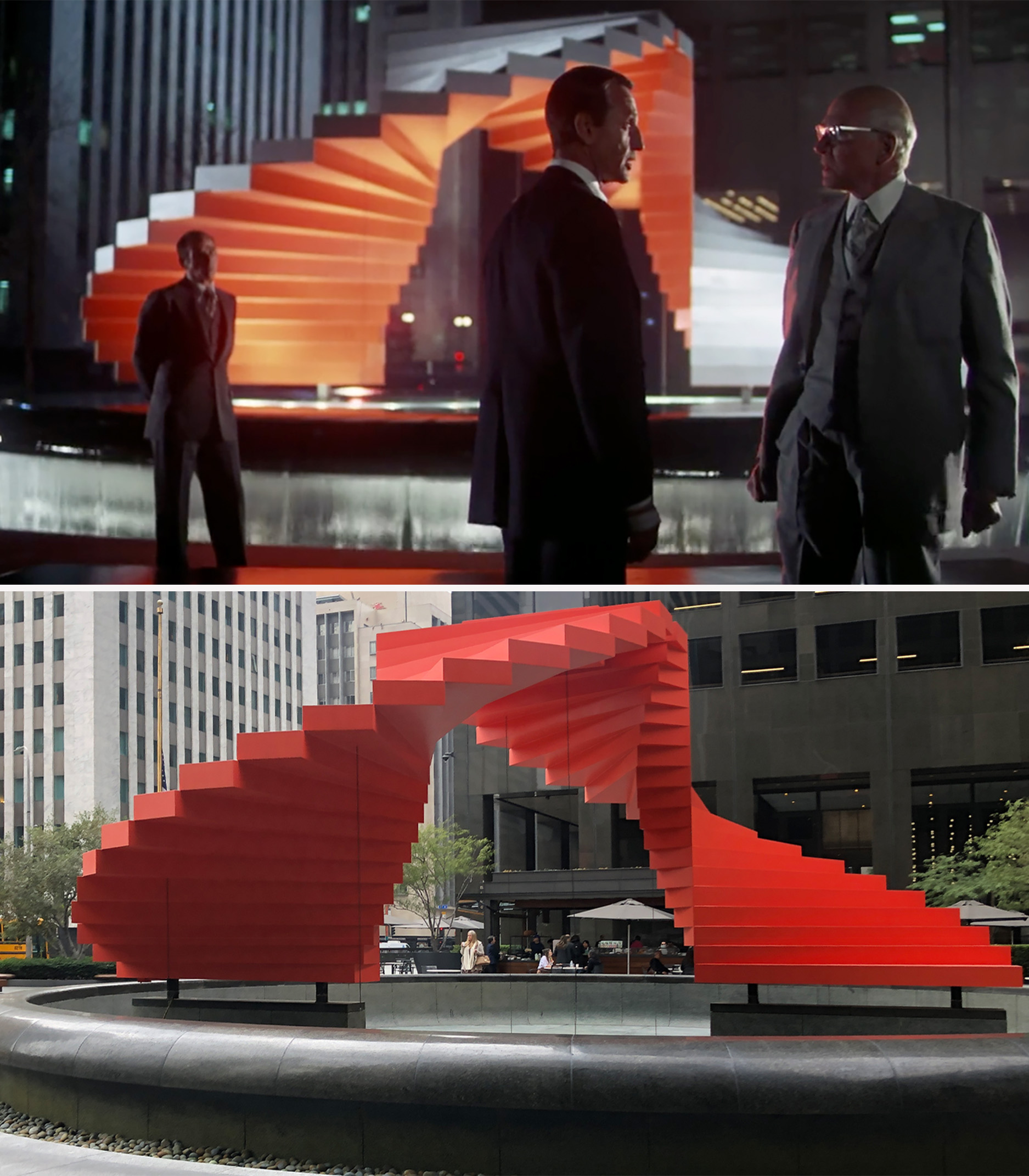

Doc is Murdered

Unlike Bethesda Fountain in Central Park, the fountain in this scene was all the way on the West Coast at what was known as Arco Plaza (now called City National Plaza), located on South Flower Street in downtown Los Angeles. This location has long-been identified, so no legwork was needed on my part, and I can only assume it was found by recognizing the large red sculpture, Double Ascension, which has been at the plaza since 1973.

While the sculpture most certainly helped modern location-sleuths in finding this location, I was surprised that none of them got the orientation quite right. Granted, the abstract art piece looks very similar from different angles, but if you brighten up the scene, you can see the large buildings in the background, letting you know exactly where the action took place. From those buildings, I concluded the actors were standing to the north of the sculpture in the plaza.

“Is it Safe?”

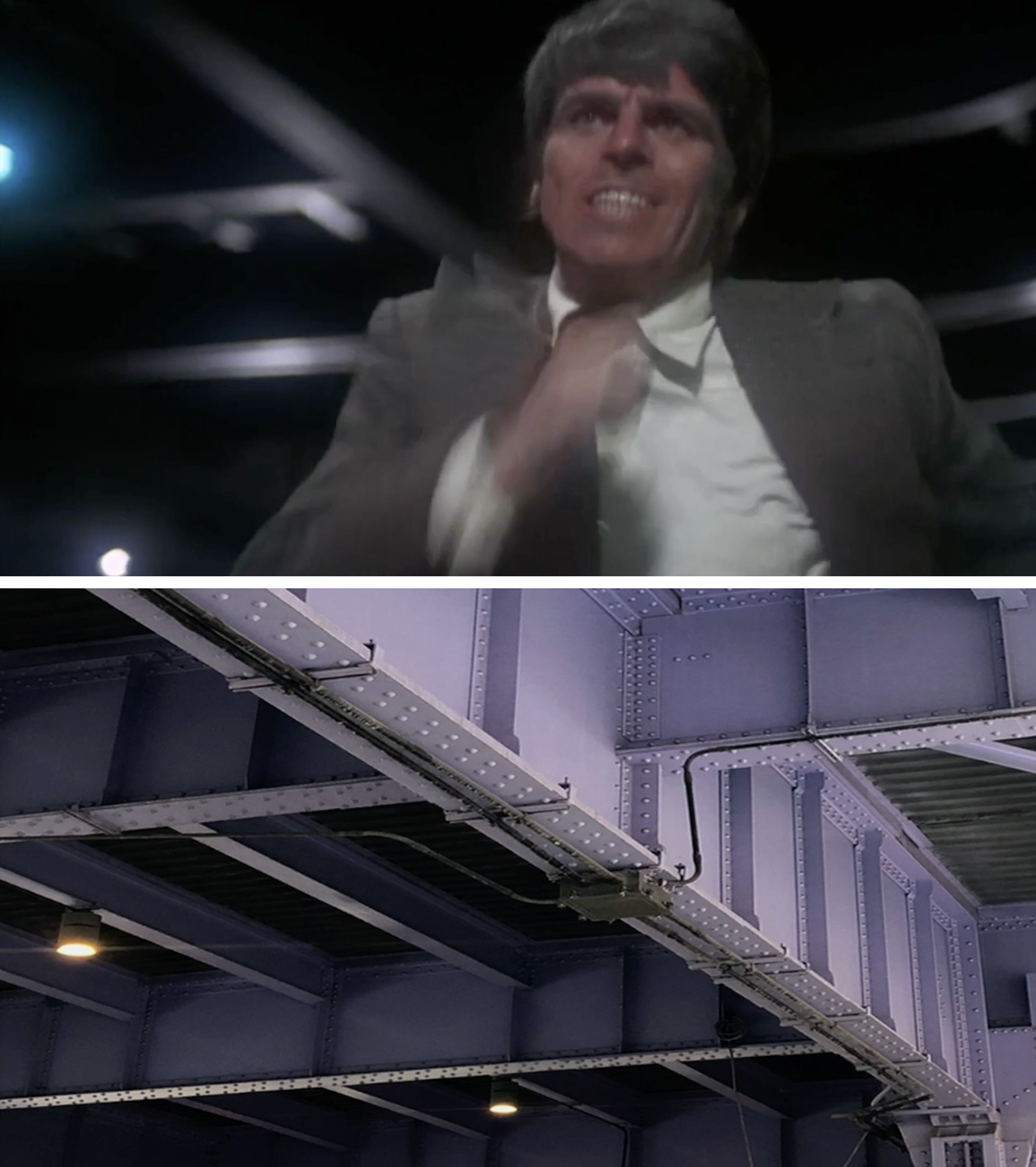

I knew early on that the warehouse (along with the interior of Babe’s apartment) was a set built at Paramount Studios in Hollywood.

After doing a little poking around, I found a plaque at Paramount indicating that Marathon Man was shot on Stage 6 (which just happened to be next-door to Stage 5, where The Brady Bunch was filmed). Given the large size of Stage 6, I can only assume most of the sets were built there.

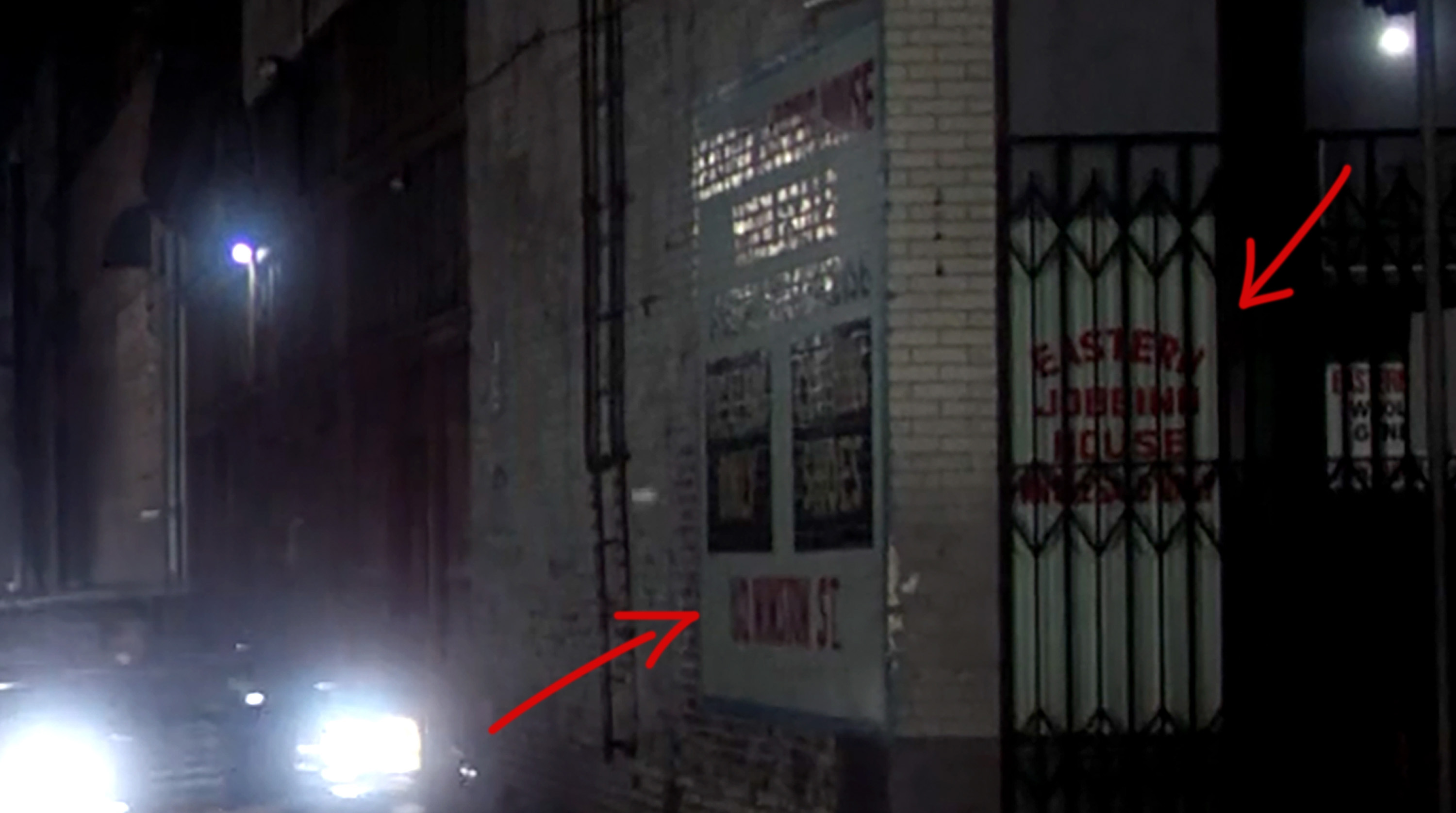

When it came to the alley outside the warehouse, for the longest time, I just assumed it was filmed at Manhattan’s South Street Seaport since it was already established that they filmed the rest of the sequence there. But after looking around the area, I couldn’t find any alleyways, eventually leading me to suspect that either they filmed in another Manhattan neighborhood or they filmed in LA.

The only clue I could find was some signage just outside the passageway, which I hoped was authentic. The clearest sign was for something called “Eastern Jobbing House,” but I couldn’t find any information of such an establishment in Los Angeles or New York.

I then looked at what appeared to be a street address painted on the side wall. It was somewhat dark and blurry, but I was pretty sure the street name began with a W and ended with a TON. The only street names I could think of that could fit the bill was Weston and Winston.

I couldn’t find a Weston in LA, but I did find a Winston, and as soon as I looked it up in Google maps, I could see it was intersected by an alley.

Upon closer inspection, I was able to find several matching details indicating that I found the correct place. And a final piece of evidence came from a Starsky & Hutch fan page that listed a bunch of businesses that appeared on the TV series. One of them was for that “Eastern Jobbing House,” which had an address of 112 Winston Street, placing it right next to the alley.

This skid row alleyway is officially called Werdin Place, but the one-block section used in this scene is more commonly referred to as “Indian alley.” It got this unofficial name in the 1970s after it had become a gathering place for indigent American Indians, many of whom were homeless. Soon after, an outreach center for LA’s Native population was established around the corner, offering a secure place to sleep and get cleaned up.

In recent years, Indian Alley’s heritage has been resurrected through a series of murals and other art installations.

When I finally got a chance to visit downtown LA, I wasn’t sure if I’d be able to enter the alley itself. Judging by Google Street Views of the alley, both ends were consistently gated and locked.

But to my surprise, when I visited the site, the southern entrance was completely open, giving me easy access. That being said, I didn’t stay very long, as the neighborhood is a bit sketchy. During the few minutes I spent in the alleyway, a couple unsocialable folks meandered in, giving me the feeling I was possibly invading their turf.

Seaport Chase

When I began working on this movie in 2016, this foot chase sequence was broadly identified as taking place in the South Street Seaport area, but the only specific spot indicated was the corner of Front and Beekman Street. I’m sure the thing that helped find this location was the former Carmine’s Bar & Restaurant at 140 Beekman.

There have been several “Carmine’s” in New York City, but the Italian seafood eatery on Beekman was often declared the “real one.” Founded in 1903, Carmine’s was the oldest restaurant in the South Street Seaport until it was forced to close its doors in June 2010 after the landlord jacked up the rent.

Its closure might’ve also been a result of waning business, likely caused by its 1980s decor and lackluster culinary offerings. During its latter years, online reviews were far from glowing, with one Yelper declaring, “I asked my date to kick me in my balls instead of take me to a joint like this next time.”

When it came to the part where they run under an elevated highway, it was obvious that it was on South Street. I was able to more or less nail the exact places used by lining up the buildings in the background, and studying the spatial relation between the support posts of the elevated FDR Drive. One good indicator of where the action took place was a neon sign for Sorg Printing in the background, which I later learned was at 80 South Street.

Before the action moves to the Brooklyn Bridge, there was quick scene of Janeway getting into a car, which was filmed in a garbage-strewn lot on Dover Street. This ragged lot was also featured in the 1971 comedy-mystery, They Might Be Giants, as well as the crime-thriller, The French Connection (1973). It’s now a fenced-in yard for the DOT.

Staking Out Babe’s Apartment

While interiors of Babe’s apartment building were sets built in Hollywood, the brief scene taking place inside his neighbor’s building was real. Luckily, when I was at the location, one of the residents happened to be taking out the trash, who then let me inside the building to take a look around. The foyer and hallway have since been updated, but the staircase is pretty much the same as it was back in the 1970s.

Aside from the paint job, the outside also looks as it did in the 1970s, but the same can’t be said about the building next-door. At some point, the left-side entrance got removed, bricked-in and relocated to the center of the building. This reconfiguration briefly hindered my investigation into a filming location from Raging Bull (1980), but things were later cleared up by a shot from Marathon Man.

The scene in Raging Bull was supposed to be the Bronx, but my research partner Blakeslee and I believed it was actually shot on W 47th. And yet, there was one thing that kept bothering us — in the scene, the doors and windows at what we thought was 440 W 47th didn’t match modern views of the building.

However, as soon as I looked up these apartment scenes from Marathon Man, I could see that the door and window placement at 440 W 47th matched what appeared in Raging Bull — thus confirming our findings.

Elsa Picks Up Babe

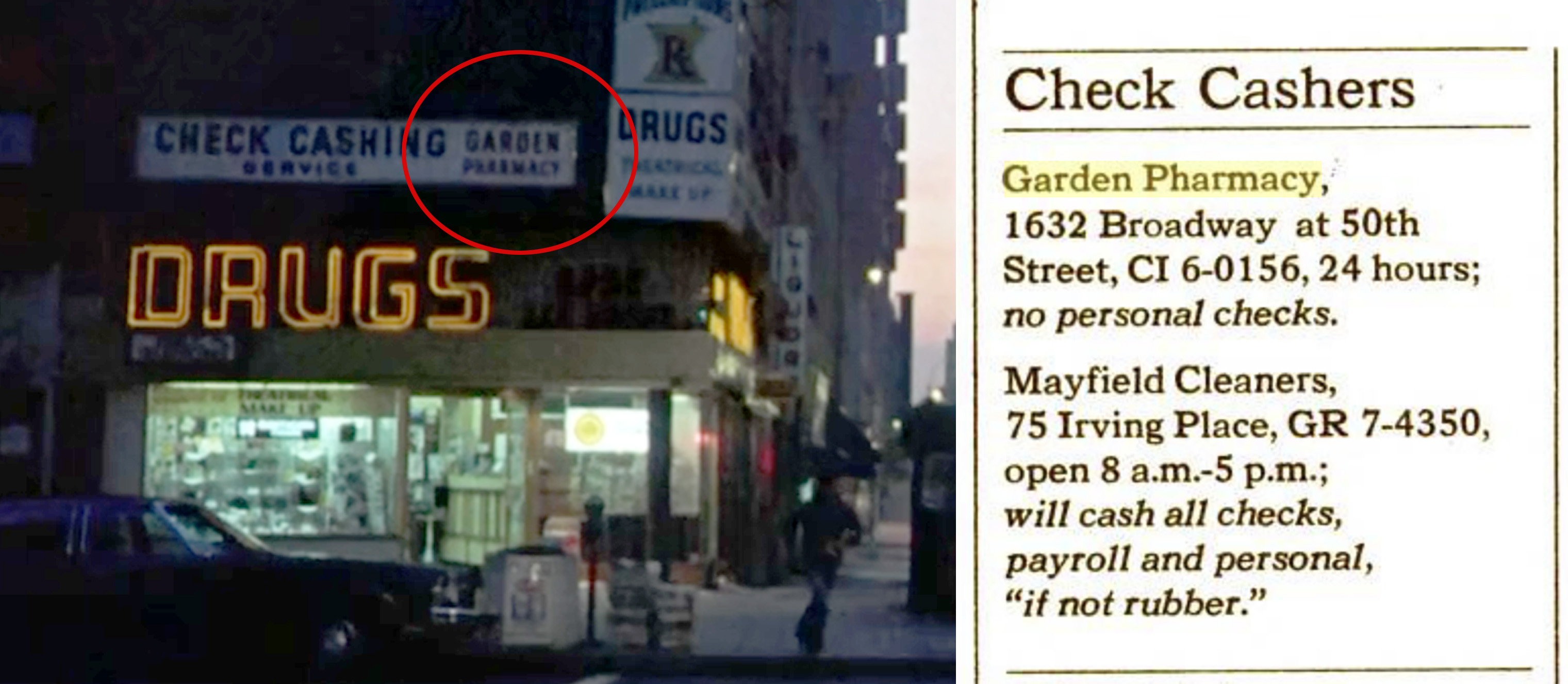

There wasn’t much work to finding this location, although the address given by Hoffman in a previous scene was off by one block.

By the looks of the location, I figured it was somewhere in Midtown Manhattan, and at one point when the camera panned, I saw what I thought looked like Times Square. But instead of just looking around that area in Google Street View, I decided to look up the name of the pharmacy seen on one of the corners.

I had to brighten up the scene to be able to read it, but it clearly said “Garden Pharmacy.” A few clicks later on Google, and I was able to find the address to the store, which was 1632 Broadway, placing it on 50th Street, just north of Times Square.

The Safehouse

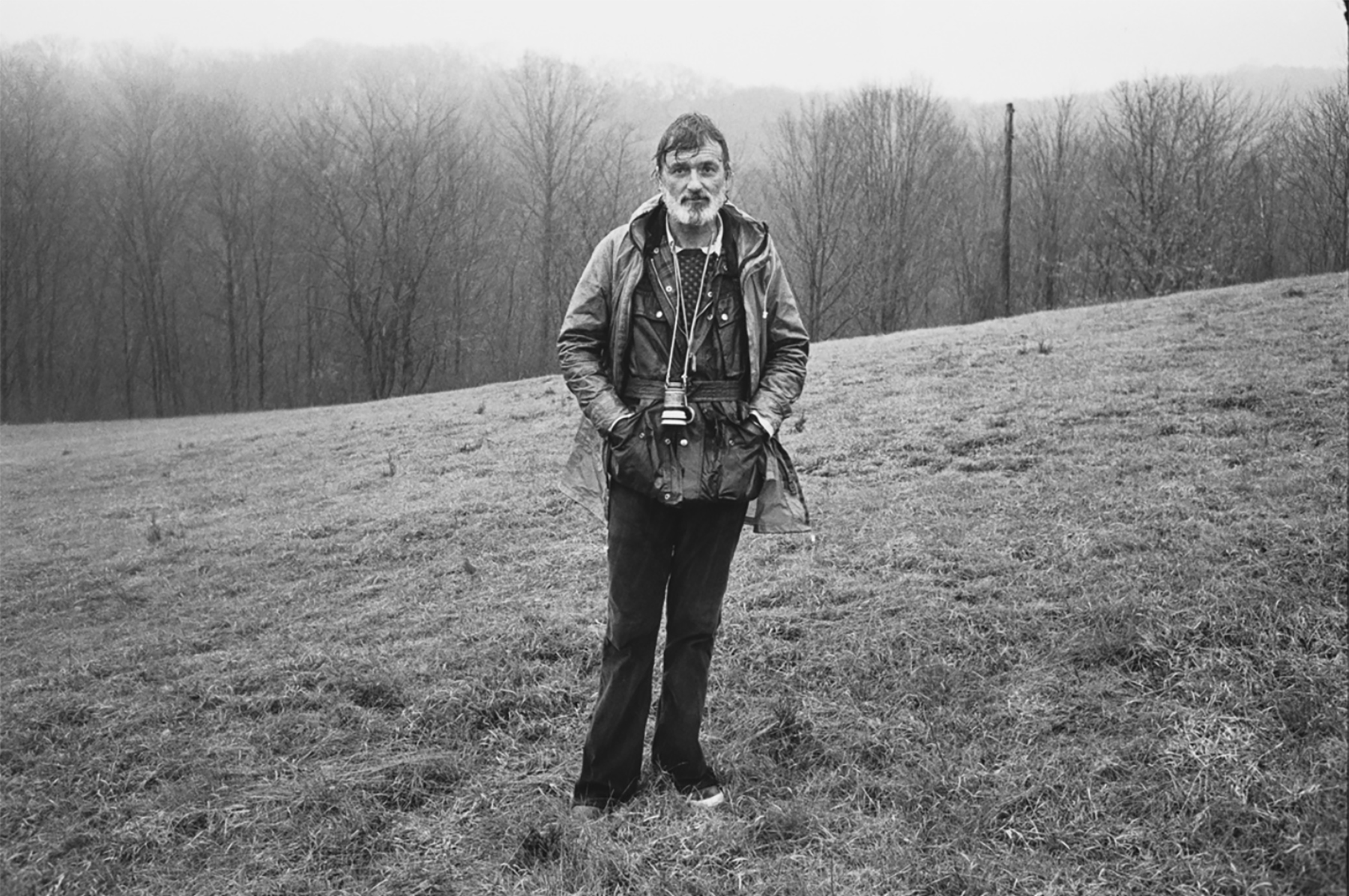

This was by far the most exciting location to visit from Marathon Man. Ever since I started investigating this movie, I had read in several places that the country home was located inside Ward Pound Ridge Reservation in Upstate New York. But I couldn’t find any photographs or even a Google Street View to be able to verify it. The only thing I was able to do was look at the Reservation in Google’s Satellite View, but all that showed was that there was a house of approximately the same size on the property.

Up until when I finally visited Pound Ridge last winter, I was unsure whether it was the correct location. Despite there being plenty of fairly reliable sources indicating that they filmed on that reservation, I knew I couldn’t be 100% sure until I got some visual proof.

I drove to the reservation in early February, not even sure if it was open. Fortunately, there was no problem getting onto the property, and because it was off-season, there wasn’t even an admission price.

I drove around the gigantic Westchester County Park, trying to get to where I thought the house was, and when I finally reached it, I was thrilled to see that it was a match. Granted, a few structural changes had been made to the house —including adding a second fireplace— and a couple of the trees had been removed, but it was unquestionably the same place.

While taking pictures from afar, I couldn’t tell if the house was a private residence or just a facility for the park staff. Just then, a park ranger exited the place, got into his truck and drove down the driveway to speak to me. I explained to him why I was there and he immediately recognized what I was talking about. He said he had to take off, but invited me to go closer if I wanted to take some more detailed pictures.

As I stood at this elusive location, all by myself in the dead of winter, there was something wonderfully eerie about it all. It was one of those moments when you feel as though you’re almost being transported back to when the movie was being made.

After many years of waiting, it was a great conclusion to my investigation into this scene.

Diamond District

Pinpointing the exact locations used in the Diamond District wasn’t too difficult since the upper floors on many of the buildings have remained the same. Plus, the sequence ends at an easily recognizable subway entrance.

The only thing that took me a few minutes to figure out was the location of the tiny shop where Szell gets an appraisal. Based on the large 24 on the glass door, I figured the shop was at what is now Daniela Diamonds at 24 W 47th Street. But I also made sure to verify the location by matching up the buildings seen in the background when Olivier exits the shop.

Now, if Ward Pound Ridge Reservation was the most exciting location to visit from this movie, Daniela Diamonds on 47th was the second. While small business owners are usually pretty amenable to having pictures taken on their property, it isn’t always a guarantee. And because I wanted to photograph a place that sold expensive diamonds and jewelry, it was hard to know how sensitive the proprietors would be.

Fortunately, Gabriel, the owner of Daniela Diamonds, knew the movie Marathon Man and was actually a little excited to discover they shot a scene inside his shop nearly fifty years ago. So, he was fine with me taking some pictures (although the shot of the door came out a little funky since the wall to the right of it is now a large mirror, creating a bit of an optical illusion).

These photos were actually the very last things I took for this article, and I did it while my friend from high school, Woodsy Young, was visiting NYC.

At first I thought he’d be annoyed for being taken to some obscure diamond shop, but he ended up being quite thrilled by the whole situation. He knew the movie (and the scene) pretty well, so he was interested to see what it looked like today, and he was also elated that the owner allowed me to take pictures inside his store.

The rest of the Diamond District pictures were taken in 2023 in the early morning before the shops opened. I made a point of getting there early because otherwise, it would’ve been impossible to get any pictures that weren’t clogged with throngs of people.

In general, from 9am to 6pm, this one block strip in Midtown Manhattan is a retail madhouse with a convo of UPS and FedEx trucks constantly coming and going.

Babe vs Szell

This last sequence from the movie jumped in geography, with the bank being the biggest jump. It was supposed to be taking place at 58th and Madison in NYC, but it was actually filmed in Los Angeles at 650 South Spring Street – a 1924-established building in the downtown area that was originally the headquarters of Hellman Commercial Trust and Savings Bank.

Like all the other California filming locations from this movie, I relied on other websites to list the bank’s address. But I’m sure it wasn’t too hard for any LA-knowledgeable folks to identify it since the Beaux Arts-style structure has been a popular fixture in cinema history, appearing in such titles as They Live, Se7en, The Mask, Ruthless People, Bridesmaids and Spider-Man 2, (which also used it to double for NYC).

Check out Lindsay Blake’s IAMNOTASTALKER website to see an array of pics from inside the former bank as well as screenshots of other productions filmed there.

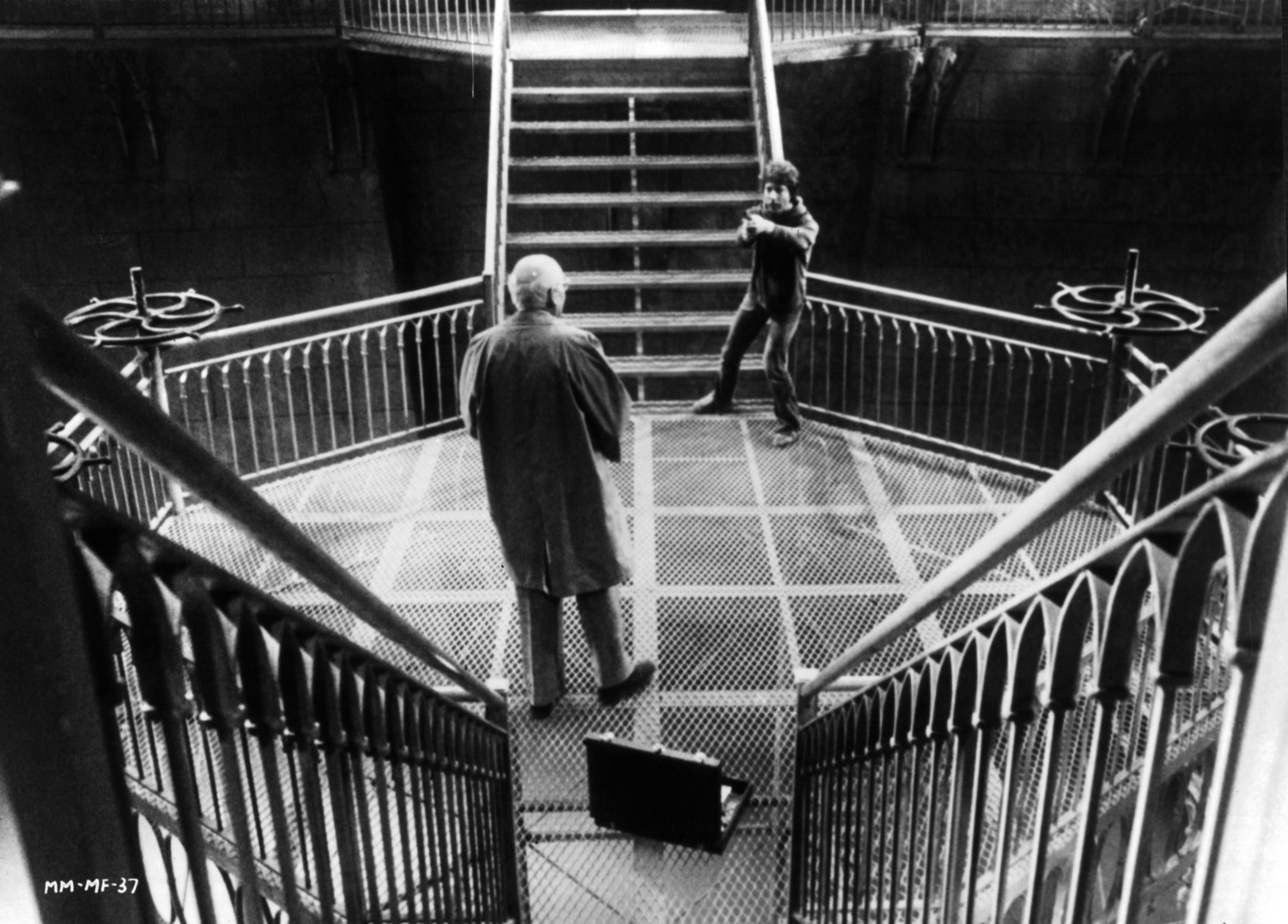

The very last scene from this sequence takes place inside the North Gate House back on Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir. But don’t bother trying to peek inside, because the interior of the real gatehouse looks nothing like what appears in the film.

The dramatic pumping station was a massive set built by designer Richard MacDonald on stage 15 at Paramount Studios.

Having the movie’s climax take place at an elaborate, almost fantastical setting was a fitting way to end this complex tale of greed and paranoia.

The fact Marathon Man seldom gets mentioned these days when discussing 70s cinema is quite unfortunate, because it is undoubtedly an inspired enigma in celluloid history. While generally considered an action thriller, it also contains many linchpins of the horror genre — even being featured in the 1984 horror movie documentary, Terror in the Aisles. It’s ceaselessly tense, fueled by themes of unadulterated evil in the form of modern-day Nazism and echoes of McCarthyism.

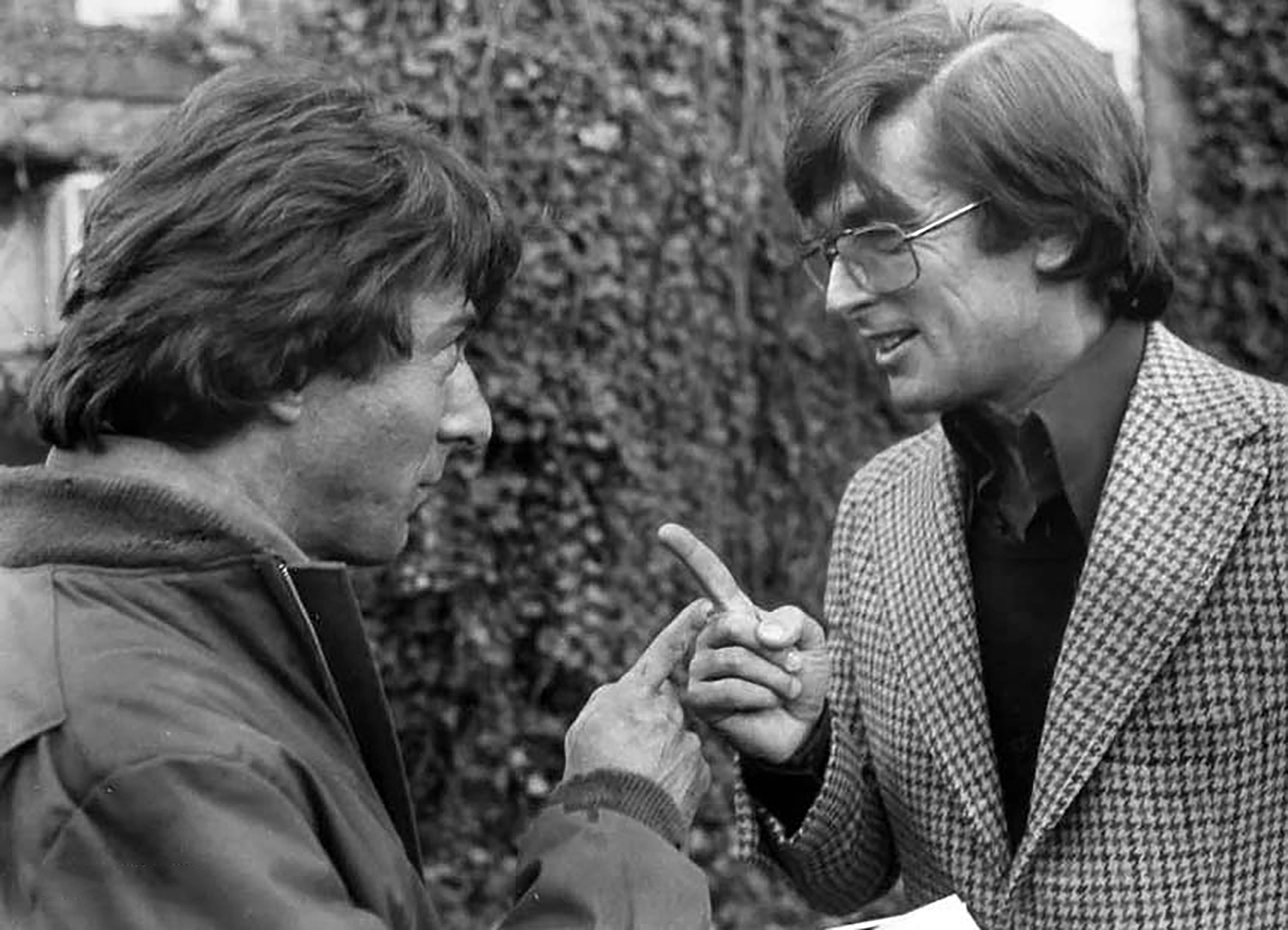

This foreboding feeling of real-life horror permeates the body of the film, crafted with calculating precision by screenwriter William Goldman (based on his own novel). And director John Schlesinger handles this white-knuckled material surprising well, considering his background was in dramatic character studies (like his previous Hoffman collaboration, Midnight Cowboy).

But these ambitious themes and intense action sequences would be essentially worthless without a great cast, and as producer Robert Evans mentioned in an interview, Marathon Man was the only time one of his pictures got every single lead actor they wanted.

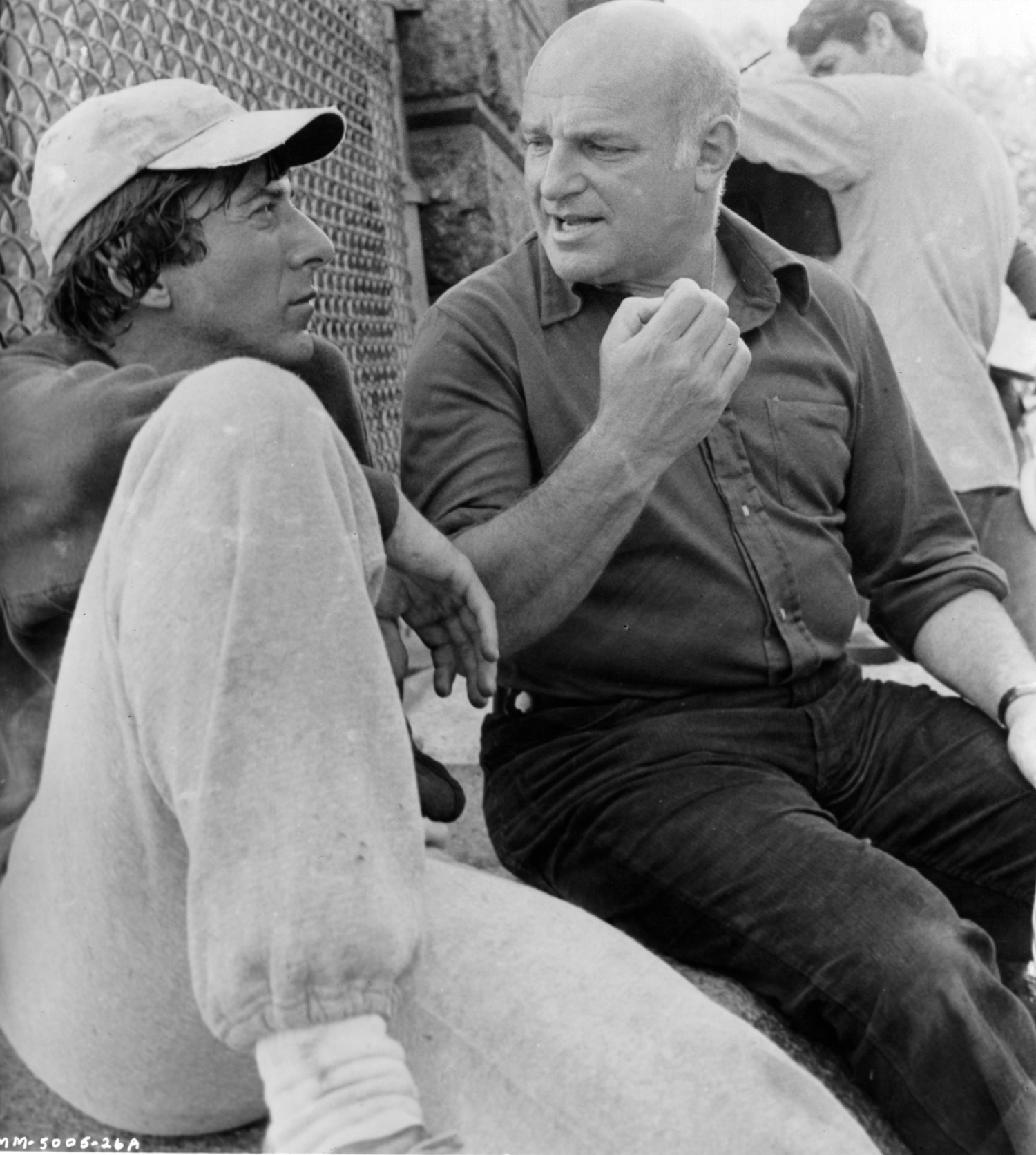

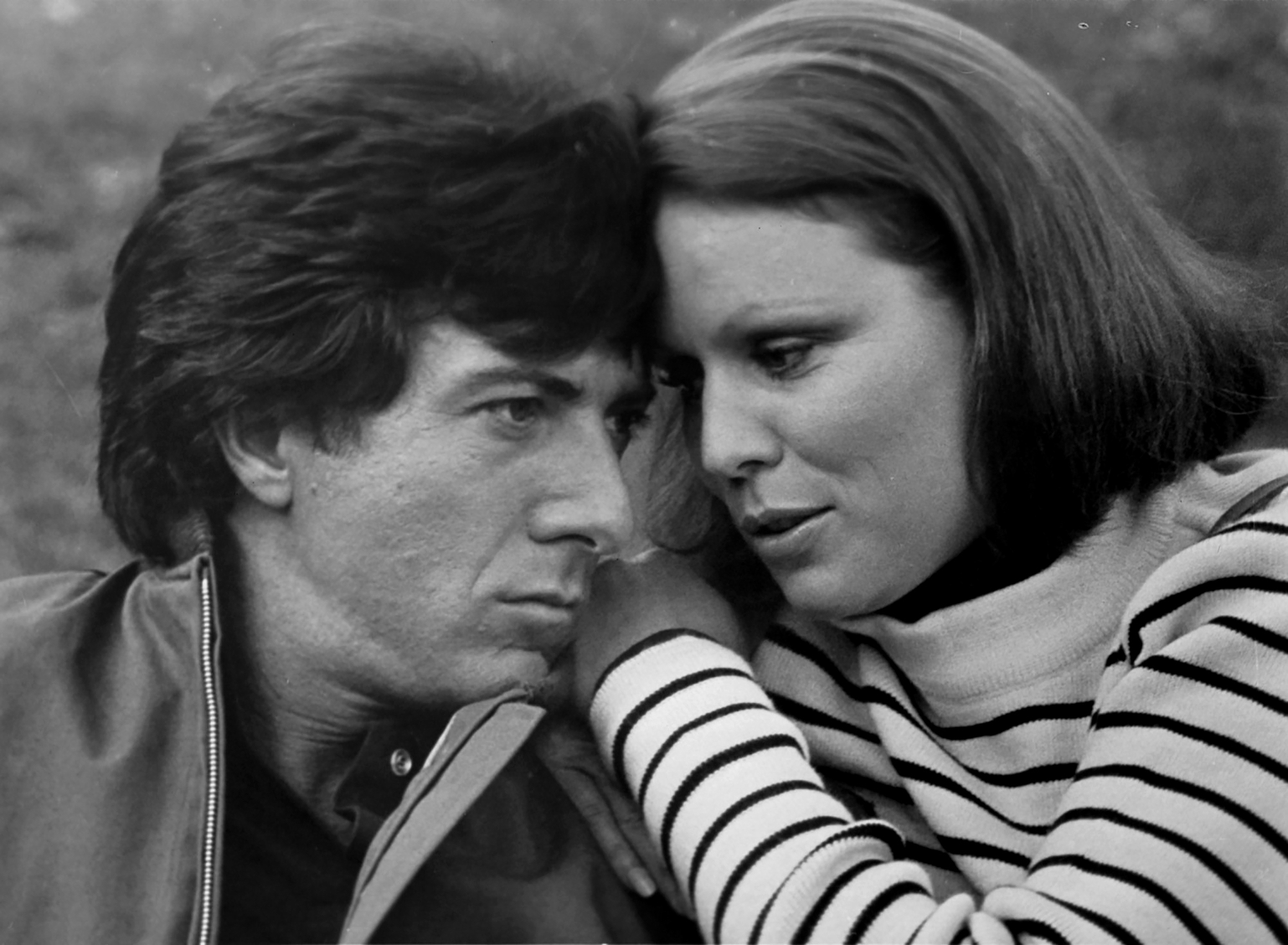

Of course, when it comes to the subject of the actors, a lot has been said about the supposed head-butting between Olivier and Hoffman, whose divergent acting styles were a source of tension, or at the very least, harsh mocking.

Olivier was classically trained, while Hoffman has long been an exponent of the Method, and it was these different approaches that purportedly led to one of the more infamous showbiz exchanges from the late 20th century. As the story goes, in preparation for filming the torture scene, where Babe had supposedly been up for several grueling days in a row, Hoffman revealed to Olivier that he too had not slept for 72 hours to get into character.

“My dear boy,” replied his English co-star, “why don’t you just try acting?”

While a great little tale, it’s hard to know how much of it is true and how much of it is apocryphal. I’ve heard that Olivier’s quip was actually an aside given to Schlesinger and not to his co-star. I’ve also heard that Hoffman has subsequently admitted his insomnia was the result of excessive partying rather than a pursuit of artistic verisimilitude.

Regardless, whatever their alleged differences might’ve been, the end result is nothing short of astounding. This is not only a testament to the actors, but also the director who knew how to exploit their differing personalities/techniques and make them work for the story.

The same can be said for the movie’s less ostentatious cast members, Roy Scheider and Marthe Keller, the latter of whom used her real-life struggles with the English language to be incorporated into her “Elsa” character.

And one of the movie’s unsung heroes is William Devane, who is pitch-perfect as a slimy government henchman. (In the original story, the Janeway character was Doc’s gay lover, which by knowing this, adds a little more intrigue into his performance.)

In addition to a great cast and a foreboding atmosphere, Marathon Man is also noteworthy for being one of the first films to employ the Steadicam, taking full advantage of this stabilization technology in the running scenes. (While Bound for Glory was the first feature to use the Steadicam, Marathon Man was the first to be released in theaters.)

Some have complained that the story is a bit confusing at times, but I believe that is by design. By doing so, it puts us in the shoes of Hoffman’s character, who is abruptly thrown into the deep end, completely unequipped and uninformed.

Bottom line, Marathon Man is a remarkable film on all levels, going far beyond basic escapist entertainment. Its diabolical fabric is present in every frame, and its themes of social atrocities still resonate today — which is a little scary.

Thanks for doing this, it was an education. I learned a lot more about the reservoir than I ever thought I would. I always wondered why they had that ridiculous fence back then, but I assumed from its small links it was to prevent throwing trash.

I also found it curious they changed the street signs in order to reflect a closer location to Colombia. It’s interesting because most films wouldn’t even bother with attention to such detail but I suppose they were counting on a lot of people knowing street locations in the audience.

Anyway, I’ve always loved this film and it’s great to see such an in depth dive into its origins. Thanks so much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. And yeah, preventing kids from throwing sticks and trash into reservoir was an alternate explanation by the city for the taller fence.

LikeLike

I’m in awe of your dedication to figuring out locations and lining up film stills and present-day reality.

Two things I’ve noticed in Szell’s walk down 47th St.: you can briefly see a bit of the Gotham Book Mart “Wish Men Fish Here” sign and, on the other side of the street, Berger’s Deli. The Gotham of course is gone; Berger’s appears to still be going (takeout and catering) on 39th St.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Doc crosses Place Vendôme but he buys a box of chocolate at 237 Rue Saint-Honoré.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fantastic as usual. Loved the bit about the jewelry store.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! This article is a serious tour de force! Never seen “Marathon Man” in its whole, but you’re making me want to watch it now!

LikeLike

This is a great article. I first saw this move when I was twelve years old in 1980. It aired on CBS and was heavily edited, but it made an impression that’s for sure. The sequence where Babe is in his bath and the two thugs come after him really impressed me – as did the midnight foot chase. The movie is now one of my longtime favorites and I watch it once a year, sometimes more. I also recommend the novel. The author William Goldman wrote the screenplay as well and the production made an effort to film some of the pivotal scenes from the novel (such as the two old men and their road rage event) in the same areas of the city. Great work.

LikeLike

What an incredible amount of work this must have been for you! I’ve always enjoyed the picture and this behind the scenes explanation made the movie all the more appreciated. Thank you for taking the time to do this!

LikeLike

great work! Congrats

LikeLike

Fantastic! I was looking on Google to identify any NYC from this movie which was the most influential movie in my lifetime of over 56 years..9I’m visiting next month). I then found this..You’ve done all my homework for me! Thanks Mark.. ” Good job” as my US rels say!

I’m Jewish by my Mother albeit not from a religious background. It wasn’t until about 1982 I had any idea of the Holocaust but my parents got the VHS video from our local video store here in the UK. My Mum watched the movie with me and in different stages explained the relevance of some of the scenes in terms of history and I became aware of my Mum’s family history, geography and the effects on members of her family which needs no further description here.

From that day I’ve always loved this movie and watched it on countless times. Thank you for this great piece of work. I’ll be visiting the key NYC locations in November for sure! Thanks again Mark.

Tom (Birmingham/UK)

LikeLike